Daughters of the Confederacy unveiling the “Southern Cross” monument at Arlington, Va., in 1917. Bettmann / Getty Images

Recent controversial comments on the Civil War from White House Chief of Staff John Kelly reignited the debate over the proper interpretation of this historic event. As many have observed, Kelly’s statement to news commentator Laura Ingraham that “the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War” is an old misconception, and in the last week it has been refuted from all corners.

But, while the facts of the Civil War and its causes are certainly important to restate in light of the controversy, it’s also important to remember that ideas like Kelly’s didn’t come about by accident. In fact, his entire statement, which elevates Confederate soldiers to heroes who fought for the noble cause of state’s rights, is indicative of the propaganda campaign of Confederate sympathizers that began in the final decade of the 19th century as they actively sought to gain control of the representations of the war in classroom textbooks.

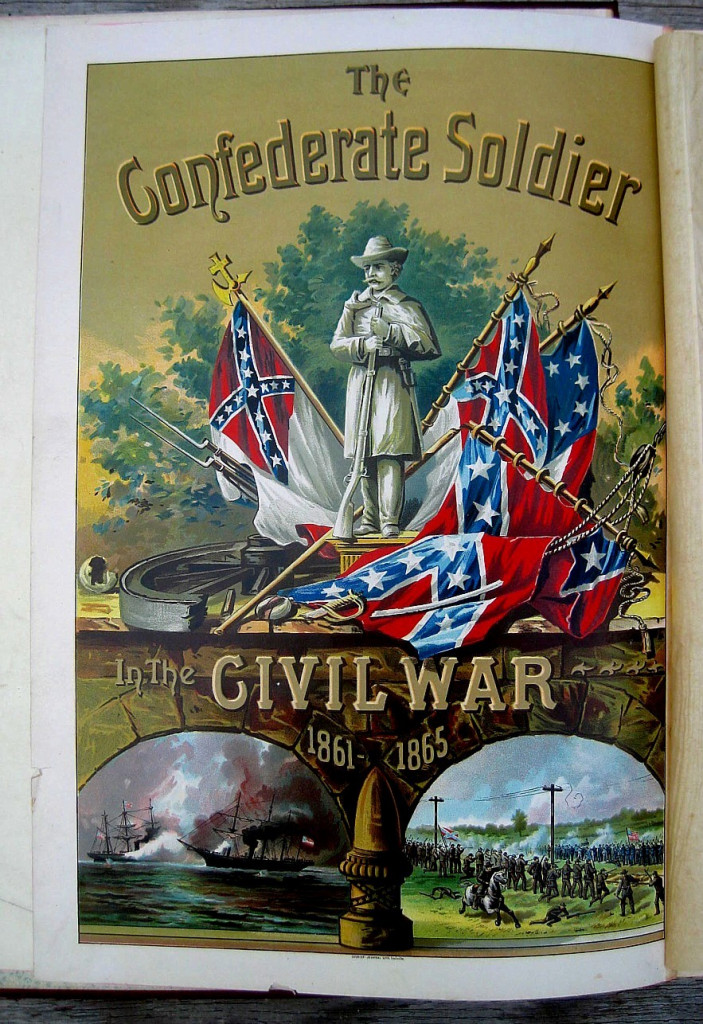

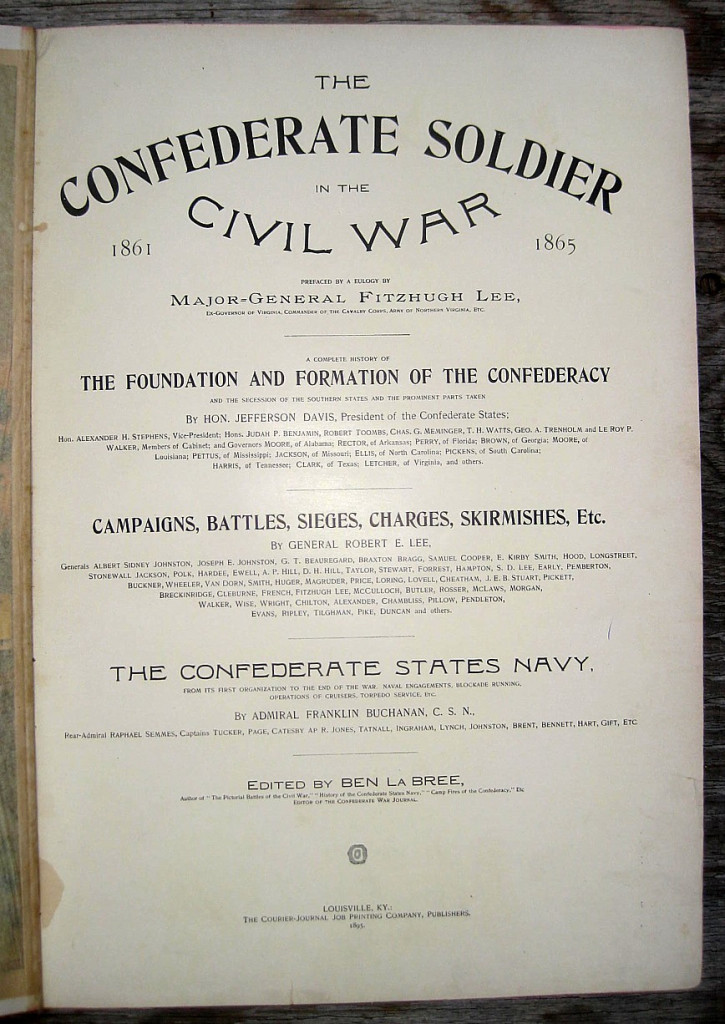

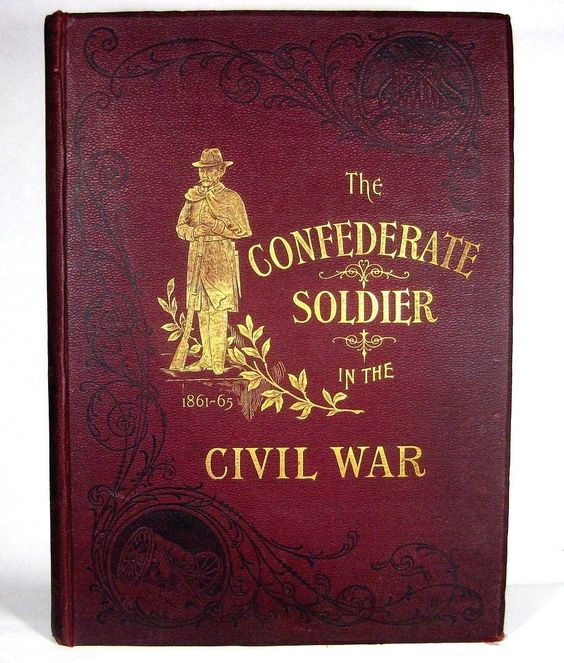

An 1895 book glorifying the Confederate soldier and featuring a complete history of the Civil War and the great Confederate generals and men who fought.

The effort to reeducate the South, indeed the entire nation, by recasting the Civil War as the “Lost Cause” was promoted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), as James M. McPherson describes in an essay in The Memory Of The Civil War in American Culture. Soon after the group organized in 1895, it created children’s auxiliaries called Children of the Confederacy with the purpose of “telling the Truth to children” — in other words, making sure that children were presented with a version of the still-recent war that placed it within the context of southern romanticism. As McPherson notes, “Children were ubiquitous at parades, rallies, and reunions of the UDC,” and those of its counterpart organization the United Confederate Veterans (UCV).

In addition, the UDC furthered Confederate education by creating a card game which was based on the traditional deck of cards comprising 52 “Confederate officers, political leaders, names of Confederate states, and of victorious battles,” to help sharpen students’ knowledge of the war; in addition, children were provided opportunities to write and recite original poems and speeches that expressed pride in their Confederate heritage. These efforts were aimed to combat what southern leaders viewed as the false history that their children had learned from textbooks overwhelmingly authored and published by northerners. Southerners complained that these texts indoctrinated southern children in a nationalism born out of a Union victory, which relegated their region to a place of dishonor in the national narrative.

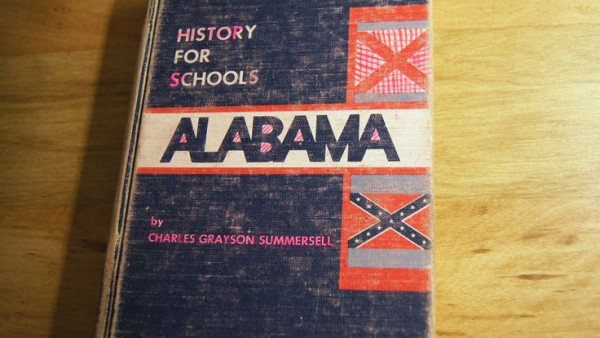

During the first decade of the 20th century, the UDC and UCV engaged in a full-scale onslaught against the textbook industry. Each organization had formed its own “Historical Committee,” which, as McPherson notes, was commissioned to “select and designate such proper and truthful history of the United States, to be used in both public and private schools of the South,” and to “put the seal of their condemnation upon such as are not truthful histories.” Hence, the committees focused almost entirely on censoring what was dubbed “long-legged Yankee lies” in textbooks that represented the North as noble defenders of the Union and the South as ignoble rebels.

By 1910, the Historical Committees declared mission accomplished.

They had won, as books that taught the “true” history of the South poured into classrooms throughout the country. Yet these southern educators did not rest on their laurels, believing there was still much work to be done. The committees’ aim was not only to oversee and control the southern narrative as it was taught in southern primary and secondary schools, but also to gain control of the southern narrative in all publications including trade and reference books. The leader of this formidable effort was Mildred L. Rutherford, a Georgia teacher and “historian general” of the UDC.

In 1916, before members of the UDC reunion in San Francisco, the first meeting of the organization held outside of the South, Rutherford delivered an address titled “The Historical Sins of Omission and Commission” in which she explicitly expressed the urgency of the committee’s duty as the official textbook watchdog. She called for subcommittees to be organized in every state to examine “all textbooks not only of American History, but American Literature, as well as geographies and readers for primary and academic grades in our southern schools; and also to inquire into text used in the colleges in the North to which our southern girls and boys are being sent.”

A prolific writer, Rutherford published her most influential work in 1919, a pamphlet titled A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries, which set forth guidelines for “the selection of textbooks for colleges, schools, and all scholastic institutions . . . in all parts of the country.” She “warned” educators and librarians to reject any book that does not acknowledge the federal interference with state’s rights as the cause for succession and the war; any book that “calls a Confederate soldier a traitor, a rebel and the war a rebellion; that says the South fought to hold her slaves; that speaks of the slaveholder as cruel or unjust to his slaves; that glories Lincoln and vilifies Jefferson Davis.”

This “measuring rod” was applied even though — while it is true that the issue of state’s rights was instrumental in the South’s succession from the Union — the fact that slavery caused the war had previously been uncontroversial. After all, as legal historian Paul Finkleman once aptly noted in a New York Times article, that “slavery and states’ rights were not mutually exclusive; in fact, they were the same thing.” Vice-President of the Confederate States of America Alexander Stephens confirmed this sentiment on March 12, 1861, in his famous “Corner Stone” speech, given one month prior to the outbreak of the war, when he stated that resolving “all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery” was “the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.”

Still, the revisionist campaign of Confederate sympathizers gained traction. By 1940, the “Lost Cause” narrative dominated textbooks nationwide; as Matt Ford observed this August in an article for The Atlantic, textbooks used when today’s American leaders were in school “downplayed the role of slavery” in the Civil War.

In 1946, the NAACP embarked on its own nationwide textbook campaign, which began in New York to fight against historical inaccuracies and for the inclusion of black history in the school curriculum. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the textbook industry began making significant changes, but the myth of the Lost Cause nevertheless continues to hold sway, as the Roper Center of Public Opinion demonstrated in 2011, on the 150th anniversary of the start of the Civil War. At that point, a significant portion of Americans — more than half, according to some polls — believed that the main cause of the war was states’ rights.

Today, the Civil War debate continues as a part of a larger conversation about the American curriculum, which includes contentions over issues such as Common Core, bilingual education, Advanced Placement subjects, and even whether history should be a required course. Indeed, the debate over what to teach and how to teach it spans over a hundred years. Textbooks are far less objective than we may imagine. They are not only a compendium of what happened in the past, but also a reflection of our present — and its politics.

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.