California is famous for the 1849 Gold Rush, but how many people realize that its gold paid for one-fourth of the Union’s Civil War expenses? The state’s important but sometimes overlooked role in the conflict gave West Hollywood a Civil War history of its own – and no, it has nothing to do with the making of “Gone with the Wind.”

• The city’s main connection to the War Between the States has all the makings of an Old West tall tale. An Army experiment begun before the war was testing camels’ suitability for military missions when it was abandoned because of the conflict. Camels that weren’t bought at auction were set free to roam Rancho La Brea, where they terrorized livestock and wild animals for several decades.

• Another link to the war is that a historic city street carries the family name of a Confederate army soldier from Mississippi, while another is named for a major in the Union infantry.

• And the final connection shows how the son of a Civil War hero was influenced by his father and his upbringing in the South as Reconstruction ended when he produced one of the most controversial motion pictures of all time.

“West Hollywood’s Civil War history isn’t as implausible as it may seem. Even though no battles were fought here, California actually had an important role,” says historian Jon Ponder, who has unearthed such tales for his website “Playground to the Stars.”

Camel Lives Matter

The Civil War featured game-changing innovations like ironclad warships for naval warfare, the Gatling gun in field artillery and hot air balloons for surveillance. California was a major testing ground for another idea the military hoped would be a similar breakthrough – using camels as cavalry pack animals to transport goods across the harsh terrain of the Southwest.

Army forts and supply lines were needed urgently to protect new territory added from the Mexican-American War in 1848 and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. Self-sustaining creatures adapted to desert conditions, the reasoning went, had obvious advantages over horses, mules and oxen that posed many challenges in their care and feeding, not the least of which was a constant need to find water. Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce, spearheaded the military’s procurement of about 80 camels and several handlers from North Africa on separate expeditions using a specially fitted ship in 1857 and 1858.

That was something a coup. “Because the British were using thousands of camels in their Crimean campaign, and Egypt had a ban on exporting the ‘ships of the desert,’ the acquisition of 33 camels on the first expedition required diplomacy as well as cash,” Smithsonian Magazine reported.

One group packed supplies from Los Angeles to Fort Tejon near Bakersfield, Calif.; others transported military goods to forts in Utah, Arizona, Texas and New Mexico, according to the California Historical Society.

The camels validated the faith of their backers right away. “The beasts carried loads of more than 600 pounds, needed little water and devoured brush that horses and mules wouldn’t touch,” Smithsonian Magazine noted. For a time, many were assigned to Drum Barracks, the California military headquarters in Wilmington, Calif., near San Pedro. Others were assigned to the Benecia Barracks in Northern California.

U.S. Route 66 First Mapped by Camel Corps

As soon as the first shipment of camels reached Texas by ship in 1857, Surveyor General Edward F. Beale was ordered to map the first wagon road west. Beale opened up a 450-mile trail from New Mexico to the Pacific Coast that would become world famous and vital for more than a century as U.S. Route 66, which runs through current-day West Hollywood.

Beale surveyed the trail 80 years before John Steinbeck immortalized the passageway as “The Mother Road” in his 1939 novel “The Grapes of Wrath.” Beale’s caravan consisted of 56 soldiers, 25 camels, eight covered wagons and 350 sheep.

The mission tested the camel’s usefulness in the new West, and also showed they were humping to please – the caravan grew to 28 camels by the time it reached California; three had been born along the way, the Los Angeles Times reported in a 1997 article.

Yet a “Camel Corps” was not to be. Smithsonian Magazine says the simplest reason is that the Civil War got in the way. “The Civil War came along at the wrong time. Once it began, Camp Verde (the Texas headquarters for the camel corps) became a Confederate outpost, and as soldiers turned away from fighting Indians on the frontier, they neglected the camels.” Plus, the caravans’ biggest supporter, Jefferson Davis, had left the Administration to lead the Confederacy as its president.

Then again, the camels helped seal the “Camel Corps” fate as well. Their ornery personality put the beast in beast of burden, according to Military Images Magazine. “Their grouchy demeanor and overpowering smell were unpleasant enough, but they also frightened dogs, stampeded horses and weren’t liked by their American handlers, who were accustomed to more submissive mules.”

West Hollywood’s First Non-Native Resident and House

The camel experiment’s demise, oddly enough, led directly to West Hollywood getting its first non-native resident and its first house being built. The Army auctioned as many camels as it could in 1863, with some being sold to circuses and zoos, others winding up as jerky and the rest being set free to roam ranchos throughout California and the desert Southwest.

Major Henry Hancock of the 4th Regiment, California Infantry, managed the auction and bought a few camels for a Los Angeles-to-St. Louis transport line he planned to launch. He also hired one of the cameleers brought over from Egypt, “Greek George” Caralambo, to run the new service. A Harvard-trained lawyer and wealthy Los Angeles landowner, Hancock lent his family name to Hancock Avenue.

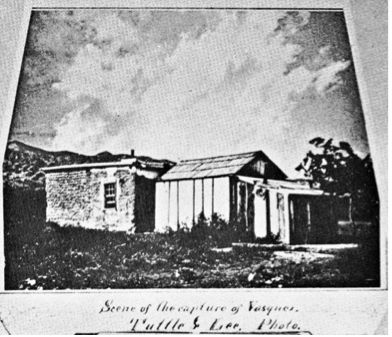

Hancock allowed Caralambo to build a farmhouse with stables for housing the dromedaries in the northwest corner of Rancho La Brea, in present-day West Hollywood. When Hancock’s plan to establish a transport line fell through, Caralambo is said to have set the camels free. They happily wandered off and were spotted foraging in the Hollywood Hills for the next 30 years.

Historian Ponder says that “Greek George” is likely the first non-native resident of West Hollywood, and his adobe cabin, which he apparently occupied by 1864, was likely the first dwelling built in the city. Historians believe it was located either at Santa Monica Boulevard and Kings Road, or a few blocks south where Melrose Avenue is today.

Confederate Lives Matter

The country’s migration westward had slowed due to the Civil War but picked up steam after the South surrendered. Many Confederate veterans joined the march for manifest destiny, believing that opportunities would be better in the West compared with the South during Reconstruction.

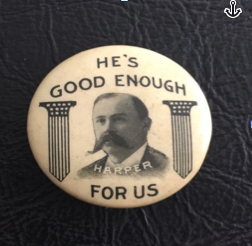

One of them was Charles F. Harper, a Confederate army veteran from Mississippi who moved his family to Los Angeles in 1868. He soon made a fortune in the hardware business and in 1895 used some of his wealth to purchase 480 acres along the north side of Sunset Boulevard, west of Laurel Canyon, where he established one of the earliest farming estates in the community of Sherman. Today, the Sunset Strip cuts through the former estate, which the family named Cioela Vista, although it is generally remembered today as Harper Ranch, Ponder’s website notes.

Historic Harper Avenue takes its name from the Harper family, according to Los Angeles County tract maps, which show the street’s name as early as 1905. The second oldest son in the Harper family, Arthur C. Harper, got married in 1887 to the daughter of a former Confederate army colonel. Harper married into a family that once owned a plantation in South Carolina with a large number of slaves.

Arthur C. Harper, who inherited Harper Ranch along with his brothers, was elected Los Angeles mayor in 1906. He was infamously corrupt and run out of office before his term ended. It seems Harper most often could be found drunk at the “pleasure houses” of the day under the guise of conducting building inspections.

Producer Lives Matter

Motion picture producer D.W. Griffith represents an entirely different kind of connection to the Civil War. He was born in rural Kentucky to Jacob “Roaring Jake” Griffith, a former Confederate Army colonel and Civil War hero.

Young Griffith grew up with his father’s romantic war stories and melodramatic nineteenth-century literature that were to eventually mold his black-and-white view of human existence and history.

Known as the father of modern film-making, Griffith was a founder of United Artists, which was located where The Lot stands today. He is most famous for “The Birth of a Nation” (1915) and “Intolerance” (1916). Griffith was hailed for his advanced camera and narrative techniques but similarly criticized for his blatant racism.

Harper Ranch, shown in this 1895 photo, was one of the earliest farming estates in the Sherman community. The man in the foreground is believed to be Charles F. Harper, a former Confederate army soldier who who moved his family to Los Angeles following the Civil War. (Photographer: Charles C. Pierce, courtesy of California Historical Society, C.C. Pierce Photography Collection)

–wehoville.com