In early May 1865, Varina Howell Davis reached the state of Georgia after having fled Richmond a month earlier. She was traveling with her four young children, her sister Margaret, two servants and a soldier who was related to the family.

President Jefferson Davis had placed the refugees from the once proud and defiant but now occupied Confederate capital under the direction and care of his private secretary, Burton Harrison (see “Davis’ flight and Lincoln’s assassination,” Coastal Point, April 17, 2015).

Davis, who himself escaped Richmond on April 2, before Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s forces marched into the city, had been on the move constantly with a contingent of government officials and a small military escort. One by one, the officials separated from the Davis party.

One of the last to go was Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, the keeper of the Confederacy’s clandestine secrets. He had burned all potentially incriminating records before departing Richmond.

If captured, Benjamin knew he would be subjected to intense interrogation regarding whether his government collaborated in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. As Gamaliel Bradford Jr. records in “Confederate Lives,” Benjamin dramatically declared “he would never be taken alive,” and surreptitiously fled the country aboard a ship in Florida — eventually settling in Great Britain, never to return nor reveal those secrets.

Having covered some 500 miles since the hasty departure from Richmond, Varina and Jefferson Davis’ parties finally joined in southern Georgia, near the town of Irwinville. As Joan E. Cashin describes in “First Lady of the Confederacy,” Varina Davis had had a premonition that they would be captured at a camp in Georgia.

Her dream became reality the next day, May 10, when a 300-man detachment of Union cavalry from Maj. Gen. James Harrison Wilson’s powerful forces sweeping across Alabama into Georgia unexpectedly came across the Davis party.

In his biography of the Confederate president, William C. Davis described what happened next. Amidst gunfire from the Union cavalrymen and confusion in the camp, Varina Davis begged her husband to flee on his own while he still could. A member of the party pointed out a nearby swamp in which Jefferson Davis could perhaps disappear.

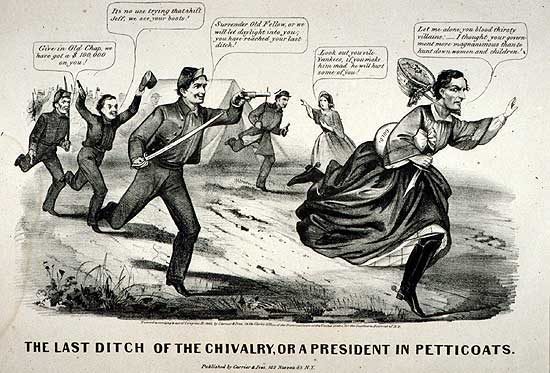

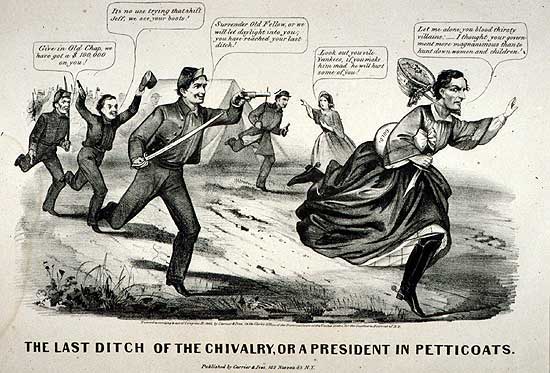

In the darkness, Jefferson Davis mistakenly grabbed Varina Davis’ raglan coat rather than his own. She threw a black shawl over his head and shoulders as he walked away toward the swamp.

At first, the soldiers thought it was a woman walking away, until Cpl. George Munger of the 4th Michigan Cavalry noticed the spurs on Jefferson Davis’ boots. He immediately rode over and aimed his carbine at the president.

Varina Davis rushed to her husband’s side when he appeared to act defiantly, causing Munger to draw back the hammer on his weapon. She grasped him from behind to keep him from moving toward the cavalryman. Jefferson Davis realized the end of his attempt to escape had come and murmured “God’s will be done.”

Meanwhile, on April 26, the second major Confederate army surrendered to its Union counterpart. Virginian Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee capitulated to Ohioan Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who commanded all Union troops in the western theater. In the small dining room of the James and Nancy Bennett farmhouse near Durham, N.C., Johnston surrendered to Sherman the 89,270 troops of the Departments of the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida.

As Robert M. Dunkerly describes in “To the Bitter End,” unlike at Appomattox when Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, there were no Union troops to oversee the process at the Bennett farm. The Confederates were left to self-police their own surrender: stacking rifles, parking artillery and turning over their battle flags.

Another large Rebel army, under Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, son of former Mexican War hero and president of the United States Zachary Taylor, surrendered on May 4 at the home of Jacob and Mary Magee south of Citronelle, Ala. Taylor commanded the Department of East Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. That was the last of the Confederate armies east of the Mississippi to surrender.

The Civil War was gradually drawing to a close. Still, a huge geographic area west of the Mississippi, known as the Trans-Mississippi Department, remained under Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s command. That department included Arkansas, Missouri, Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), Texas and Louisiana west of the Mississippi.

Smith remained defiant, desiring to “prove to the world that [our] hearts have not failed.” Yet, with President Davis’ capture and the surrender of the other three main armies, uncontrollable circumstances would soon impose a final decision.

Bethany Beach resident Thomas J. Ryan’s latest book is “Spies, Scouts & Secrets in the Gettysburg Campaign” (June 2015). Contact him at pennmardel@mchsi.com, or visit his website at www.tomryan-civilwar.com