About a month after the Civil War began, a slaveholding ancestor of current U.S. Congressman French Hill seemed confident about the future. “Lincoln can’t starve me out unless he takes my land and negros,” plantation owner Creed Taylor wrote to a relative.

By the time the war ended in 1865, President Abraham Lincoln had freed the enslaved, including at least 70 who worked Taylor’s cotton fields here. But Taylor’s family found a path back to prosperity that didn’t look much different from the way he had first made his fortune.

In May 1861, Creed Taylor wrote to his brother to explain his support of secession. Via Arkansas State Archives

Taylor still owned at least 1,500 acres of farmland. By the turn of the 20th century, his grandson oversaw a sprawling cotton operation that would eventually grow to more than 10 times the size of Taylor’s farm. And for years, the fields would be worked once again by Black people who didn’t have a choice.

Emancipation dealt many slaveholders a staggering economic blow, wiping out vast amounts of wealth across the South. In 1870, five years after the war ended and about 4 million Black people were freed from slavery, the states that once made up the Confederacy were enduring one of the largest wealth shocks in American history. The reported wealth of Southerners dropped by $4.3 billion, or about 65%, from a decade earlier, a Reuters analysis found. Put another way, war and emancipation appear to have erased about two-thirds of wealth in the South.

For this story, Reuters traveled to Arkansas and Georgia, and interviewed more than 20 experts on Southern history and economics. Journalists also used thousands of pages of newspaper accounts, census documents, court records, history books, family papers and other material to construct this story. The data analysis of the wealth shock in the South is based on a comparison of 1860 and 1870 census data from IPUMS.

Those who lost the most, like Congressman Hill’s direct ancestor, were the largest enslavers. They also had the clearest path to rebuilding – often by replicating elements of the slavery economy and reinstituting feudal systems that embraced white supremacy.

The Black people who had been enslaved emerged with far less. Racial violence and voting laws locked them out of political power. Schooling was limited, leaving most unable to read and write. The federal government let former slaveholders keep their land, and the newly freed were afforded few paths to prosper – leaving them once again at the mercy of the white elite.

In a report published in June, Reuters found that a fifth of the U.S. political elite – congressional members, living presidents, Supreme Court justices and governors – are direct descendants of slaveholders in America. Among the richest just before the Civil War were the forebears of three members of today’s Congress: Hill, Representative Dina Titus and Senator John Kennedy. Each had a slaveholding ancestor who was among the wealthiest 1% of Americans in 1860, Reuters found. By 1870, each of those forebears had lost between 60% and 90% of their wealth.

What remained, however, was land – and key social and political connections that, a 2021 study concludes, proved critical to the financial recoveries of the largest slaveholding families.

Such connections, Reuters found, helped the ancestors of Hill, Titus and Kennedy. In each family lineage, for example, at least two slaveholders or their descendants married descendants of other enslavers, pooling their assets and increasing their influence as they shaped the South’s postwar economy.

“The power of enslavers came not simply from their ownership of property, but from their ability to wield political power and from their clans,” said Steven Hahn, a professor of history at New York University who studies slavery, capitalism and the U.S. South.

Hahn said he believes that some lawmakers in both political parties benefit from advantages that stem from the slaveholdings of their ancestors. “And to this day,” he said, “their power and wealth can’t be dissociated from that.”

In examining the lineages of Hill, Titus and Kennedy, Reuters focused on how their forebears reclaimed family wealth and power in the decades following the post-war Reconstruction era. It was a time when the old South sought to reassert itself socially and politically, stripping away the rights Black people had gained during Reconstruction before federal troops withdrew from the region in 1877.

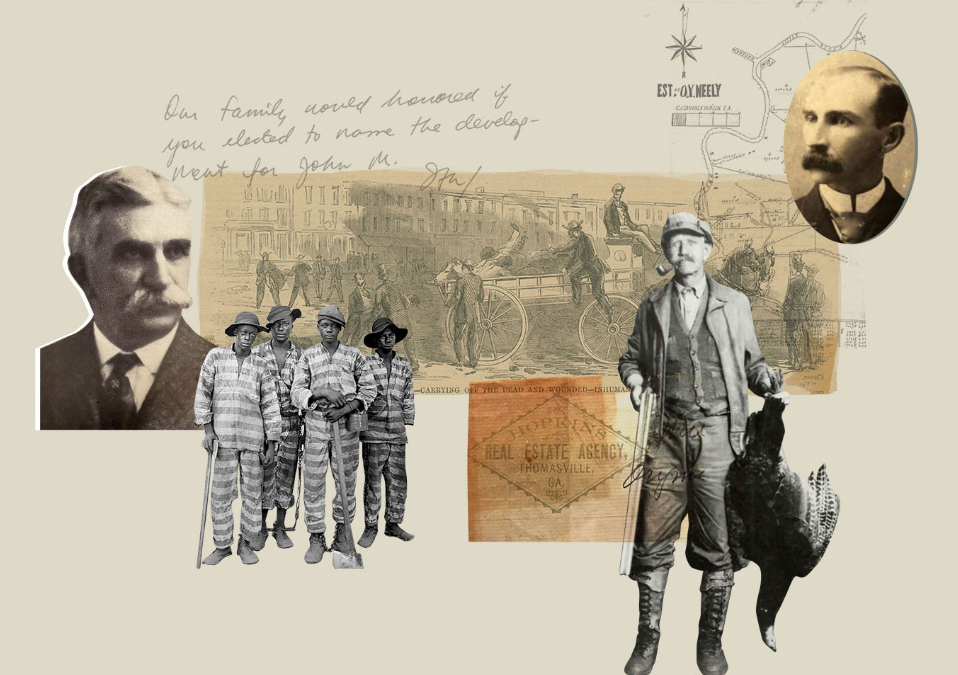

Hill’s great-great-grandfather leased prisoners, most of them Black, to pick cotton and handle other farmwork for pennies a day in Arkansas. Unlike the people Hill’s ancestors enslaved, the prisoners represented labor without substantial investment.

A forebear of Titus married the daughter of a former congressman and slaveholder, and became a regional power broker in politics and real estate. In an address to state lawmakers, he explained that “in Georgia, the white race intended to dominate the negro race and control the government of the state, no matter how large the negro majority,” according to a newspaper account at the time.

And Kennedy’s ancestors expanded the family’s Louisiana land holdings through marriage and inheritance, then used poor Black farmers to work the land. Family estate records and an interview with a descendant of one of those farmers suggest the family used both sharecropping and tenant farming, which effectively kept some of their Black neighbors in debt.

As Black people were denied basic rights, the strategies used by the ancestors of today’s political elites illustrate key facets of the legacy of slavery in America. Taken together, they make clear how the descendants of some of the largest former slaveholders regained prominence and wealth by subjugating Black people in new ways after 1865.

“At the moment of emancipation and the end of the Civil War, when there could have been a massive redistribution of wealth to the people whose forced labor had created it, that did not happen,” said Heather McGhee, author of The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together. “Instead the plantation class reorganized itself and the laws to ensure continued privilege – and privilege built on the exploitation of Black labor.”

Determining how much of a family’s money today came from an ancestral slaveholder is exceedingly difficult. Fortunes made through chattel slavery – or through the abusive labor practices in the decades after emancipation – were lost, built upon or divided among multiple heirs over many generations.

But more than cash wealth was passed down. Slaveholding had enabled families to buy land and invest in other industries. It allowed access to top schools for their children, giving their descendants entry into prominent occupations. And it helped them foster relationships with other leading families, building connections that reinforced their economic interests, said Joshua Rosenbloom, an economist at Iowa State University who has studied wealth before and after the Civil War.

“At the moment of emancipation and the end of the Civil War, when there could have been a massive redistribution of wealth to the people whose forced labor had created it, that did not happen.”

While the formerly enslaved were “essentially turned loose without any assets and had to support themselves,” the wealth accrued through slaveholding provided a cushion for white families that allowed them “to suffer short-run losses” but continue to take risks, he said.

“We still have this notion of America as a land of opportunity,” Rosenbloom said. “Understanding the extent to which that’s true and the ways in which it’s constrained is central to understanding our own self-image and understanding how people succeed.”

In approaching the three lawmakers, Reuters asked about the ways their forebears regained their wealth and standing in the post-slavery South. “None of them bear any personal responsibility for the specific actions that their ancestor did,” said Douglas A. Blackmon, author of Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. But in learning about the choices their forebears made, Blackmon said, the legislators should “consider what that history means.”

Neither Hill nor Kennedy commented specifically for this story. In June, Hill issued a statement for a previous Reuters story, calling slavery “a scourge” and saying “we as a nation must recognize our past, learn from it, and look to the future.” In 2019, Kennedy called slavery “reprehensible,” but noted: “I believe in personal responsibility, and I just don’t think someone today is responsible for what someone else did 150 years ago.”

For this article, Titus provided a statement: “Slavery is a deplorable part of our history, and I have no bonds with any long-dead relatives connected to it. We must not forget the cruelty visited upon Black Americans over generations as we commit to systemic reform that ensures equal rights for all. That principle has guided my personal life, professional career, and political record.”

The Use of Convict Leasing

The early childhood of John M. Gracie, an ancestor of U.S. Representative French Hill, was swaddled in the wealth produced by slavery. When Gracie was 4 years old, his father enslaved 11 people in New Gascony, Arkansas. Nearby, grandfather Creed Taylor enslaved 70. Combined, their estates would be worth as much as $119 million today – almost all of it in the value of their land and the Black men, women and children they listed as personal property.

After emancipation, the family retained its land. But who would work it? Gracie began experimenting with a variety of solutions after taking over from his grandfather in the 1880s, including using poor Black farmers and immigrant laborers from China.

But another option would prove lucrative, speeding the family’s path to greater prosperity and landholdings: leasing prisoners from the government.

Convict leasing involved paying the state or county for the use of prisoners, most of whom were Black. After Reconstruction ended, Southern legislatures enacted racist laws that diminished the rights of Black people and provided the pretext to jail them for petty transgressions. Often illiterate and struggling to make a living, they were ill-equipped to defend themselves in court or pay the fines that followed.

Southern states used the system to address budget deficits and inadequate prison capacity after the Civil War, while providing a cheap and essentially disposable source of labor to the highest bidder.

“Convict leasing was a method of truly resurrecting something that looked almost exactly like the slavery that had existed before the Civil War,” said author Blackmon, who teaches at Georgia State University. “It was not typical for convicts to go back into the exact same kinds of plantation settings … but Arkansas was a place where that did happen.”

Unlike purchasing the people Gracie’s ancestors enslaved, leasing prisoners didn’t require a substantial up-front investment for landowners. And if prisoners died doing the backbreaking work, others could quickly take their places.

Gracie signed contracts with local governments to use prisoners. They were housed on Gracie’s land, and the conditions were grim, according to newspaper accounts and government reports from the time. Men were whipped. Others died of heatstroke. One lost a foot to frostbite. At least a dozen prisoners, mostly Black men, lost their lives on Gracie land from 1890 to 1905, according to newspaper and state reports.

In 1888, for example, a state board reviewed a report by the penitentiary physician that examined the conditions at several prison labor camps. The report found 44 prisoners at a Gracie camp who, when not doing hard labor, were confined to a windowless pen measuring 20 feet by 20 feet. Ten years later, a Black man named Caesar Washington sued Gracie.

Washington had been pardoned by the governor of Arkansas, who noted his poor health. A petition presented by a government attorney mentioned, too, the fine and offense that put Washington on Gracie’s farm: $5 for “disturbing the peace by using profane and insulting language to a colored woman.”

In his lawsuit, Washington alleged that while serving on one of Gracie’s prison labor farms, he was “brutally beat, struck, whipped, kicked and maltreated.” The assaults were so bad, the 67-year-old shoemaker said, that he was left “wholly and permanently incapacitated from earning a living.”

Reuters could find no record showing how the suit against Gracie was resolved.

Amid similar allegations of mistreatment, Gracie thrived. He expanded the family’s farming operations, clearing thousands of acres of land around New Gascony and buying additional plantations near the Arkansas River. In 1908, news accounts said Gracie controlled 23,000 acres of land across multiple plantations and used as many as 250 prison laborers at a time.

Gracie’s precise profits are unclear. As of 1902, his contract with Pulaski County, for example, indicates he paid the local government 25 cents per day per prisoner, according to a newspaper account. Around the same time, the state of Arkansas’ own convict leasing operation, with a daily net cost of 27 cents per worker, produced a net profit of 48 cents – nearly twice as much as the cost of its labor.

After a 23-year run, Gracie ended his profitable business of using convict labor in 1909, as lawsuits and government investigations kept stacking up. In newspaper stories, Gracie had referred to the lawsuits by former prisoners as an “attempted hold up,” though he allowed that “it is impossible to handle a large number of convicts without sometimes resorting to somewhat extreme means in order to maintain discipline.”

But Gracie’s brutal practices didn’t affect his community standing. He was revered by white people in the Little Rock and Pine Bluff areas, where Gracie served as a senior executive for a bank and a railroad company. He supported local Catholic causes, helping to finance a school for Black children.

He and his family lived in Little Rock, in a Greek-revival mansion that he bought for as much as $7.6 million in today’s money. There, his wife and daughters threw parties for as many as 175 people, decorating with magnolia blossoms and Japanese lanterns.

After he stopped using prisoners and Black tenant farmers, Gracie turned to Italian immigrants. But he soon soured on the Italian workers as “money mad” – they complained of debts they couldn’t work off and poor conditions, including holes in the floors of their cabins and rampant malaria. Many Italians left Gracie’s plantations. By 1918, several hundred Black tenant farmers once again worked his land, despite Gracie’s published comments years earlier in which he referred to Black laborers as “irresponsible, dishonest and very poor workmen” – a common racist trope.

His cotton empire began to crumble after prices crashed in 1920. Gracie would lose his farmland and sell the mansion in Little Rock. But in the lineage that leads to Congressman Hill, the family’s standing endured.

In 1924, Gracie’s granddaughter married another prominent Arkansan. Gracie died at the age of 76 in 1933 – the same year his granddaughter’s husband, James “Jay” Wilson Hill, established one of the first investment banking firms in the state.

Today, Gracie’s great-great-grandson is an accomplished member of Congress, representing Arkansas’ second congressional district since 2015. As a teenager, James French Hill worked summers at the family brokerage firm before attending Vanderbilt University. By his 30s, he was a U.S. Treasury Department official and a senior economic policy adviser to President George H.W. Bush.

In 1999, Hill helped found a Little Rock-based financial firm, Delta Trust & Banking Corp. Hill served as chairman and chief executive officer there.

Hill has shown a deep appreciation for history, describing himself as a ninth-generation Arkansan and serving as a commissioner for the Historic Arkansas Museum.

In 2011, when the former Gracie mansion was renovated with a loan from Hill’s Delta Trust bank, Hill wrote to the new owner. “Our family would (be) honored if you elected to name the development for John M,” the note read. It was.

In 2015, when Hill was sworn into Congress, he used a family Bible. It had been passed down from John M. Gracie’s father, a slaveholder.

Hill’s latest public financial disclosures show his net worth at between $10.3 million and $25.7 million, including his Little Rock residence. His holdings include a family investment vehicle with a name that echoes his family’s ancestral plantation: “New Gascony Company, LLC”.

Powerbrokers and the Leisure Economy

In 1820, Francis Hopkins enslaved 183 people on his cotton plantation along the coast of Georgia. The son of a British naval officer, Hopkins also was a member of the state legislature. He is the great-great-great-great-grandfather of U.S. Representative Dina Titus – and the single largest slaveholder among the ancestors of America’s political elite identified by Reuters.

Titus, in her seventh term in Congress representing the state of Nevada, is the direct descendant of at least seven slaveholders, Reuters found. Five of those ancestors lived in Georgia, where Titus was born and raised.

After the Civil War, the son of Francis Hopkins reached out to the local branch of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the agency set up to assist the formerly enslaved during Reconstruction. Thomas S. Hopkins, who had also been a slaveholder, lodged a complaint, bureau records show. “The ‘Freedman’ on his plantation refuse to work,” it read, and “he wishes them removed.”

The message was a sign of things to come for the Hopkins family and the place they called home: Thomasville, a town in the deepest reaches of south Georgia.

Many Southern landowners clung to farming, but this branch of the Hopkins family was largely forsaking agriculture. Thomas Hopkins was a physician, and by 1871 the mayor of Thomasville. Three years later, he presented a paper to the Medical Association of Georgia.

Dr. Hopkins contended that his town was the ideal place to recover from “consumption,” as tuberculosis was then called. In an 1882 letter published in the Atlanta Medical Register, he extolled the virtues of Thomasville’s “dryness of the climate” and the city’s distance from the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, with their dangerous “saline vapor and moisture.”

His pitch, made through travel advertisements and testimonials to medical journals, effectively rebranded Thomasville as a destination for the ailing. The city was highlighted in a Harper’s magazine article in 1887, which described it alongside winter resorts that included the south of France, Switzerland and the Adirondacks.

The son of Dr. Hopkins continued those efforts. But as Henry W. Hopkins himself became a prominent political figure, he used the family name and influence to launch an even greater transformation of Thomasville – one that in some ways capitalized on recreating elements of the antebellum South.

Often referred to as Judge Hopkins for one of the many offices he would hold, Henry married the daughter of a former U.S. congressman, who had also been a slaveholder. For parts of five decades that followed the end of Reconstruction, Judge Hopkins was one of the most influential men in the region.

From the mid-1880s through 1900, Hopkins spent nine terms as Thomasville’s mayor. When he wasn’t at city hall, he served in the state legislature – for 17 years between 1894 and 1926. Family papers reviewed by Reuters show Judge Hopkins traded favors with newspaper editors and politicians. He helped wealthy Northerners and Midwesterners, including Standard Oil heirs, acquire land, then hosted elaborate hunting trips. In the off-season, he often managed the plantations they bought.

In and around Thomasville, he built a social dynasty by brokering the sale of these plantations to monied outsiders, drawn to hunt quail and experience the old South.

Southerners like Hopkins “basically ran these places like their fiefdoms,” said historian Hahn. “And poor white people and poor Black people were expected to bow down to them.”

These were “big families who wielded an enormous amount of patronage and either occupied local offices or had clients who did,” he said.

Through his law firm and real estate brokerage, Judge Hopkins “compiled, and eventually sold, almost every one of the original plantations that now are such a wonderful part of our southern life,” according to a book written by his great-grandson.

In the world Judge Hopkins helped create, the old plantations became country lodges. Well-to-do white people attended Christmas fox hunts and “fancy dress” balls where they danced the Virginia reel. Black families worked on those properties as servants and hunting guides. Part of the allure for some Northerners came in touring the homes of the county’s poorer Black residents.

“When it becomes clear that there is interest in vestiges of the old South … there’s a real sense that you can sell this,” said Julia Brock, a history professor at the University of Alabama who co-wrote a book about Thomas County and surrounding areas.

“There was a real interest in Black life,” Brock said. But that interest was in the nostalgia of the antebellum South, “not Black life as it was emerging into freedom.”

The economic success of the country-lodge plantations recaptured some of the Hopkins family’s standing as “part of a gentry,” Brock said, conferring upon him “a central place in a new social world.”

The system that now offered leisure for the wealthy still depended on Black labor, from tending dogs to driving carriages to serving supper to making sure quail nests were safe from natural predators.

It was “a feudal-type thing” for Black people, said Titus Brown, a history professor at Florida A&M University.

Brown, who co-wrote a book built around interviews with former employees of area plantations, said working on the leisure plantations was like living in a bubble. That leisure economy provided Black families with jobs and other benefits, including medical care and access to education. And it granted them “some protection, as long as they are not violating the social conduct or etiquette,” Brown said.

Judge Hopkins’ life and livelihood exemplified the nature of that social contract.

After a school for Black students burned down in a neighboring county, Hopkins donated land for a new location in Thomas County. He also connected Black people whom he knew to the white families who owned the plantations, recommending them for plum jobs.

But Hopkins had also been an early member of the Ku Klux Klan, and he sought to reassure white people that his vision for the region wouldn’t upset their primacy.

In 1905, for instance, state lawmakers debated whether to create a new county by peeling land from Thomas County and an adjacent county. Critics argued doing so would give Black residents an electoral advantage in two of the counties. Hopkins favored the move, and he testified before state lawmakers. According to The Atlanta Constitution, Hopkins “devoted his time to answering the argument of the opposition relating to negro domination,” and “closed with an eloquent reference to the fact that in Georgia the white race intended to dominate the negro race and control the government of the state, no matter how large the negro majority.”

Judge Hopkins was in his 80s when sociologist Arthur Raper visited Thomasville in the early 1930s. Raper sought to explore the reasons behind lynchings in America, and two had taken place in Thomas County in 1930.

In one case, a Black man was accused of attacking a 9-year-old white girl. The man was jailed, and a mob gathered. When authorities tried to move the man to a different location, the mob wrenched him from the sheriff and told the man to run. Then they shot him repeatedly from behind.

The mob tied the man’s body to the back of a car and dragged him through town, his corpse almost hitting a pedestrian, Raper wrote. The killers did not bother covering their faces, according to Raper’s account. Still, no one came forward to identify them.

Raper wanted to learn more about the leaders of a town where such a thing could happen. Among those he interviewed was Judge Hopkins.

Hopkins and other leading citizens of Thomas County, Raper wrote, saw themselves as above poor white people. The sociologist referred to them as the “local landed aristocracy” and wrote of their paternalistic attitude toward Black people. Raper paraphrased it as: “Why you know, that fellow’s grandmother belonged to my mother’s father.”

Hopkins, he wrote, called lynchings the work of lower elements of white society: “I’ll give anybody a thousand dollars who’ll find either a son or a grandson of a slaveowner participating in a lynching.”

Raper found that Hopkins had once been a member of the Klan – using the phrase “the original Ku Klux Klan.” He was referring to the group’s first incarnation, when the Klan rose during the federal occupation of the South in the Reconstruction years. Writing in 1932, Raper said Hopkins had recently declined to join the reconstituted Klan.

Hopkins’ great-grandson later wrote of watching Judge Hopkins meet with “a group of hooded and sheeted figures” assembled on the lawn. They had come to ask him to “join in some sort of mission or action.” Judge Hopkins, according to his great-grandson, told the men to contact the police if a law had been broken. Otherwise, Hopkins told them, “you men must go home and hang up your robes for good.”

Judge Hopkins had no need to circumvent state power. He and others like him now were in control. Hopkins lived into his 90s, dying in 1945.

His great-great-granddaughter, Dina Titus, was born in Thomasville and grew up in Tifton, a town about 50 miles to the north. She graduated from the College of William and Mary, earned a master’s degree from the University of Georgia, then got a doctorate at Florida State University. She taught government for more than 30 years at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Like her forebears, she pursued a career in politics. In 1988, she was elected to the Nevada State Senate, where she served as Democratic minority leader for 15 years. In 2008, she was elected to Congress.

Disclosure forms and real estate records show her net worth at between $978,000 and $2.5 million. The median U.S. family had a net worth of $193,000 in 2022, according to a survey for the Federal Reserve Board.

The Paralyzing Debt of Sharecroppers

The farm fields of Catahoula and Concordia parishes made white men rich and Black men miserable for many years in central Louisiana. Fed by a sprawling set of waterways, Concordia’s floodplains turned into what some call “million-dollar soil,” sprouting rows thick with cotton that were flanked by towering plantation homes.

Central Louisiana is where the ancestors of U.S. Senator John N. Kennedy came to secure their fortunes. In 1840, less than 30 years after Louisiana became a state, Kennedy’s great-great-great-grandfather enslaved 120 people in Concordia Parish. His estate in 1860 was worth about $57 million in current day dollars. His ancestor’s brother, a farmer and politician, enslaved 55 people on his Mississippi land in 1860. He then used cash from that estate – worth some $68 million in today’s dollars – to buy nearly 1,800 acres in neighboring Catahoula Parish.

After the Civil War, when the Black people they had enslaved were freed, the forebears of Kennedy were never again as rich. But they remained monied and powerful – a lineage of doctors, politicians and landowners surrounded by poor Black families.

Marriages between the descendants of slaveholders further grew their holdings. Among the senator’s direct ancestors was his great-grandfather, Leonidas Calhoun, who controlled large swathes of land along or near the Mississippi River Delta.

Calhoun went to medical school in Kentucky in the 1880s, then returned to live on a family plantation in Catahoula Parish. From there, he practiced medicine and oversaw hundreds of acres of farmland in Catahoula and adjacent Concordia Parish. He died in 1903 at age 44.

At the time of his death, estate records examined by Reuters suggest that the Calhoun family was both sharecropping its land and also renting out larger tracts to tenant farmers.

In sharecropping, landholders typically gave farmers the right to live on and farm their land in exchange for a portion of the crops they produced. Farmers – those around the Calhoun land were typically Black and illiterate – often needed credit from their landlords simply to put a crop in the fields. Owners would front them everything from food and clothing to seeds and tools, typically provided at inflated prices and sold at stores on the plantations themselves.

After harvest, whatever was borrowed was deducted from the sharecropper’s earnings. In bad years, many may have owed more than they earned. Until those debts were repaid, laws forbade sharecroppers from leaving.

“During the end of the year, when it’s time for settlement, (landowners) would then pull out these accounting records to say, ‘Oh, you and your family almost made it out of debt,’” said Cassie Sade Turnipseed, a history professor at Jackson State University who has studied sharecropping in the Mississippi Delta.

Using the appraisal of Calhoun’s assets and matching them with census records, Reuters identified at least two Black farmers who owed Calhoun money at that time.

One was Granville Swift. Records show he owed $20 to Calhoun, and the debt was already at least six months past due. The 1900 census shows that Swift, a 23-year-old Black farmer, lived with his 22-year-old wife, who was a farmhand. Both were illiterate. Swift is also listed as a farmer in Catahoula Parish in the 1910 census, and records indicate he died there in 1918, at age 42. Reuters could find no evidence that he ever owned any of the land he farmed.

Another Black farmer who owed Calhoun money was Ben Polk. His debt was $5, according to estate records. The 1900 census for Catahoula Parish shows 49-year-old Benjamin Polk. He was listed as the head of a household with 10 other mouths to feed: his wife, eight children and one grandchild.

At some plantations, the owners issued their own scrip for use at their stores. Turnipseed, the scholar of sharecropping in the Mississippi Delta, said this meant that, even in profitable years, sharecroppers were unable “to acquire any kind of wealth because your currency would only be honored in very limited ways” on the plantation.

In an interview with Reuters, Ben Polk’s great-granddaughter recounted her ancestors’ description of working the Calhoun land.

Men in the family labored “sun up to sun down” in the cotton fields and had little autonomy, said Bettye Johnson, now 75. She said they were forced to buy food and goods on credit and at inflated prices in a plantation general store. Their debts often dwarfed their earnings, Johnson said.

“It was the Calhouns’ place,” Johnson said, “and they were in charge.” In the 1930 census, the occupation for Leonidas Calhoun’s son, who inherited the family land, was listed as “overseer” of a plantation.

The struggle to earn a living was intensified by violence and racial animus, some that was chronicled by the Calhoun family itself.

Legacy of Slavery

The 1870 census shows the dramatic disparities after the end of slavery between Black and white people in Concordia Parish, Louisiana.

•

•

•

Source: Reuters analysis of IPUMS data.

During Reconstruction, Black residents of Concordia Parish gained power at the voting booth.

In 1860, about 91% of people living there were counted as “slaves,” the third-highest percentage of any county or parish in the United States, according to data from a recent study. After emancipation, Black people outnumbered white people in the parish 9,257 to 720.

Those figures underscore how important slavery was to families including the Calhouns, and how different the post-slavery political landscape became during Reconstruction. In the 1870s, Black men in Concordia were sheriffs and district court clerks. A formerly enslaved man was elected to the state legislature and then founded a newspaper.

A book by a local historian named Robert Dabney Calhoun, a nephew of Leonidas Calhoun, provided a window into how at least some local white people viewed those results. Black officeholders, Robert Dabney Calhoun wrote, were “illiterate, dishonest and sweating” men who carried out “unscrupulous designs.”

“Our substantial citizens were forced to engage in election manipulations,” wrote Calhoun. “They prayed for the dawning of the new day of white supremacy.”

That is what the white people of Concordia and surrounding parishes established for decades, by unleashing a deadly campaign in the 1870s.

“Lynchings, massacres, and terroristic intimidation was absolutely central to how many plantation dynasties reasserted dominance,” said John Bardes, a history professor at Louisiana State University, whose studies focus on slavery in Louisiana. “It was just horrific spasms of violence all throughout the state.”

A recent report by the The Equal Justice Initiative found that Louisiana ranked third in the nation between 1877 and 1950 in what it terms “racial terror lynchings” – killings that were “acts of terrorism” outside of any legal proceedings. The state had 549 such murders in that period, the group found.

Around the time Leonidas Calhoun took control of the land in Concordia and Catahoula parishes, white people across the South had succeeded at reasserting political dominance. Another report by the Equal Justice Initiative notes that, “from 1885 to 1908, all 11 former Confederate states rewrote their constitutions to restrict voting rights using poll taxes, literacy tests, and felon disenfranchisement.”

Near the turn of the 20th century, changes in Louisiana tightly restricted who could vote. In 1897, before the changes, state records show 164,088 registered white voters and 130,344 registered Black voters. After the changes, records show 125,437 registered white voters and just 5,320 registered Black voters in 1900. The year after Leonidas Calhoun died, the number of registered Black voters across all of Louisiana had dropped to 1,718.

Today, the great-grandson of Leonidas Calhoun is the junior U.S. senator representing Louisiana. John Neely Kennedy – his middle name is the surname of two of his slaveholding ancestors – was president of his senior class at Vanderbilt University. He graduated from the University of Virginia School of Law, and earned a degree in civil law from Oxford University in England. Before being elected to the Senate in 2016, he spent five terms as Louisiana’s treasurer.

Real estate records and Kennedy’s latest public financial disclosures show his net worth is between $8.3 million and $22.6 million.

Kennedy doesn’t live in either Concordia or Catahoula parish. But after his mother died, he was named as one of the inheritors of her estate. Among her possessions listed in a 2005 probate document was hundreds of acres in Catahoula – family land that once belonged to one of Kennedy’s slaveholding ancestors.

A REUTERS SERIES

PART 1

INTERACTIVE

PART 2

PART 3

PART 6

–reuters.com