Legend has it that the city of Laurens owes its existence to a brandy bottle.

One day in the early 1800s, a group of men took a drinking break while looking for a place to build a new courthouse. One of them tossed an empty bottle, which landed on a hill. Upon closer inspection, the woozy group found the spot to be the ideal location for their new building.

A new courthouse soon grew from the site, forming the center of what would be the public square. From there, the fledgling city spread out in all directions to form what many consider to be the most perfect shape: a circle.

Circles have long been revered for the elegant symmetry of their curvature. They symbolize wholeness, unity, continuity. Their shape is utilitarian, used for wheels, roundabouts, coins and clock faces. And so too do they provide the basis from which to build a community.

Pulling out a map of South Carolina, you can count 30 towns formed in the shape of a perfect circle. If you put your imagination to use, you can find several more that share a roughly similar symmetry.

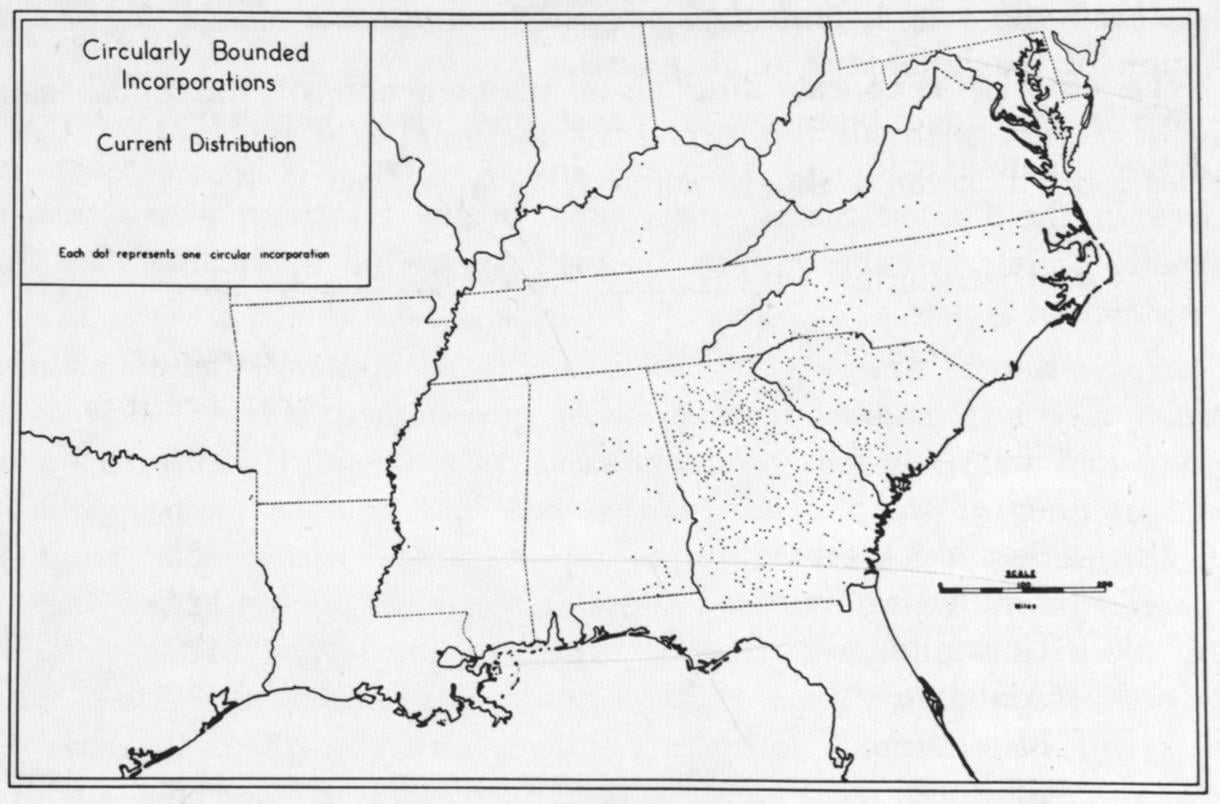

No other place in the world has as many circle towns as the South. And there used to be many more.

Of the 317 towns incorporated in South Carolina between 1783 and 1938, The Post and Courier found 184 towns that used a circular shape to define their original boundaries.

The Palmetto State shared an affinity for round towns with one of its neighbors. Of the 620 circle towns that existed nationwide by the middle of the last century, four out of five were in either Georgia or South Carolina, University of Georgia researcher Howard Schretter noted in his 1957 paper Round Towns.

But just how did they come to be, and why? And what happened to some, like Laurens, which lost their perfect curvature over time, taking on the dimensions of omelets and other odd shapes?

To find those answers, one must follow a trail through history, a path now buried in dusty archives, crinkled maps and research papers long ago shelved in the annals of academia. It is a tale of southern destiny, of steam-powered progress opening thick forests and rugged backwaters to settlements that would become the cities and towns we know today.

It is a tale very much our own.

A mysterious Southern Style

Circle towns first appeared in the Piedmont region of northeast Georgia. Warrenton, the county seat of Warren County, in 1810 became the first to establish circular boundaries. Other towns soon followed suit, including Sandersville and Lincolnton, according to a 1977 study by Mineaki Kanno, another University of Georgia researcher.

The trend jumped across the Savannah River in 1829 to Barnwell County, which neighbors Georgia. The village’s incorporation paperwork speaks to its circular shape, describing its boundaries as extending “three-quarters of a mile from the place where the courthouse now stands.”

Barnwell was one of the first 11 circle towns incorporated in South Carolina before 1850. Others included Edgefield, Lancaster and Laurens. All were county seats that recognized the courthouse as their center.

This wasn’t a coincidence. People were moving into South Carolina’s interior, but these remote outposts had small populations with limited public services or amenities. The courthouses served as more than a place to address legal disputes. They became trading spots and centers for civic life.

As they grew, these communities opted to formally incorporate into cities and towns as their residents sought urban services such as law enforcement, sewer lines or road maintenance.

One 1827 petition from a Barnwell resident, for example, sought incorporation to allow for law enforcement that could address “many evils to the morals and good order of society frequently occur.” The act that incorporated Barnwell allowed it to form a council “for preserving health, peace, order, and good government” within the village.

But why circles? Why squares?

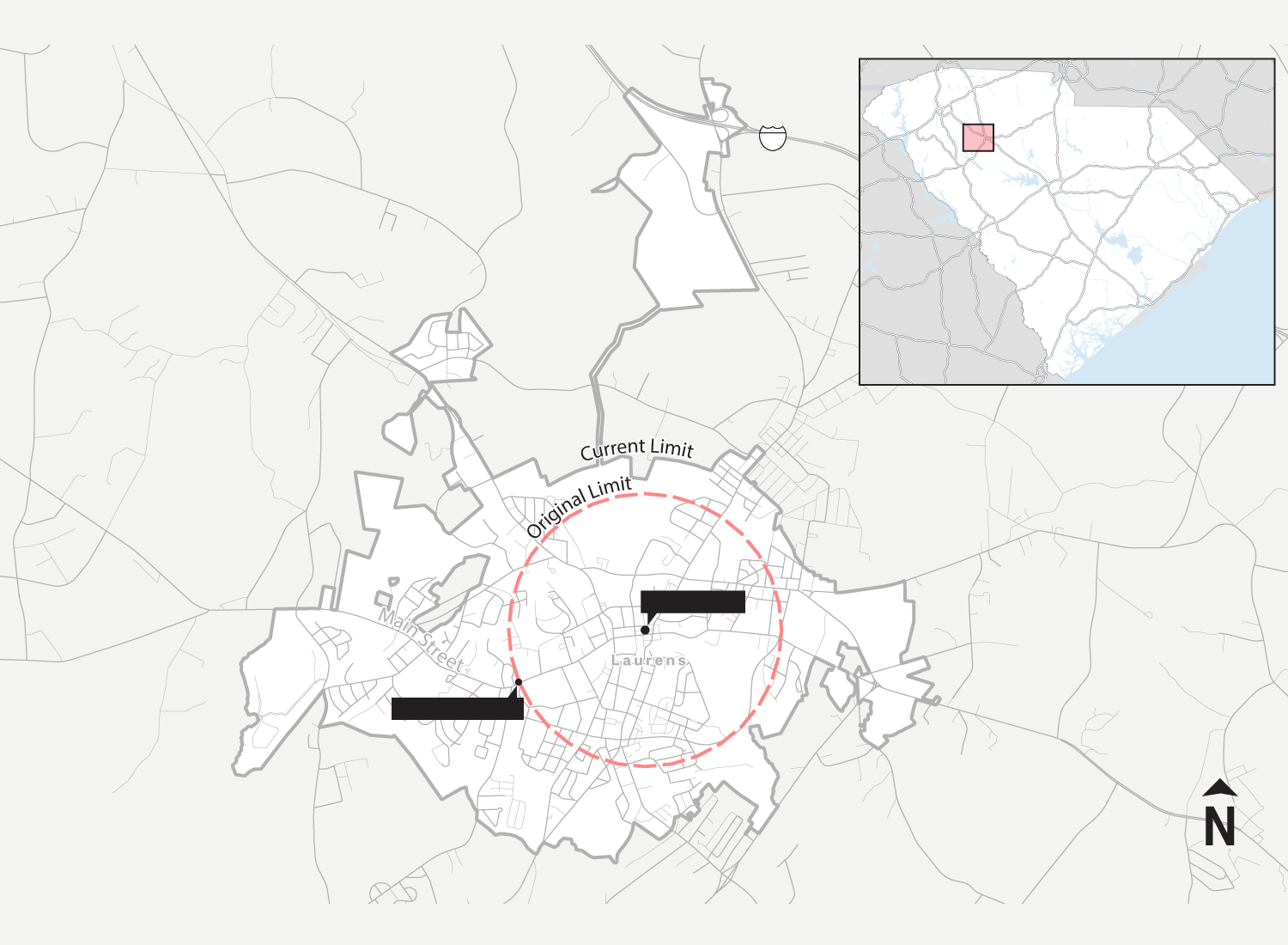

In Laurens, a lone granite marker stands between the pavement and sidewalk at the intersection of West Main Street and Todd Avenue. The number “1” engraved on it has worn away over the years and is now almost impossible to read.

The marker once stood among many milestones erected after the city’s incorporation in 1845 to mark its circular perimeter, Mayor Nathan Senn said. The worn stone is now the last marker standing.

When it incorporated, Laurens established borders that “extend one mile in each and every direction from the Court House.” The paperwork doesn’t explain why it did so, but Senn believes the decision was rooted in fairness, with the founders giving equal measure to all parts of the city.

Laurens had a limit extending one mile from the courthouse

N.C.

385

S.C.

Ga.

Courthouse

Laurens

Granite Marker

HONGYU LIU/STAFF

SOURCE: SCDOT

Schretter, the UGA researcher, found no legal mandate requiring towns to incorporate with circular limits. He believed their founders adopted the shape because it was easy to lay out and describe in documents, without the need for an expansive land survey. Circles also provided a way to give equal measure to all parts of town, since its territory all radiated from a central point, he said.

“To such communities the one requisite of a boundary is that it encompasses the towns’ urban core, that area to which urban type services will be provided and from which taxes will be collected,” he wrote. “Since a circular limit can readily satisfy this need and still meet legal boundary requirements, it is ideally suited to the smaller community.”

However, some cities and towns, including Patrick in Chesterfield County, found similar benefits in establishing their borders as perfect squares. And others, such as Brunson in Hampton County, appear to borrow a little from both shapes, overlaying a square center within the constraints of a round border.

Towns with square and rectangular borders became fairly common across the United States as the country spread west. Chopping up parcels along a grid was a simple way to divide territory and make it all fit together.

Circle towns, over time, became a phenomenon largely unique to the South, Schretter wrote in his 1957 study. They simply didn’t make sense in other regions, he found.

Towns in New England, for instance, sprung up in small, dense states and tended to have irregular shapes as their borders crowded up against one another, he stated.

South Carolina had more room within its borders to spread out. And that would play a key role in the growth of circle towns as a new breed of iron horses charged forward into the state’s untamed interior in the name of progress.

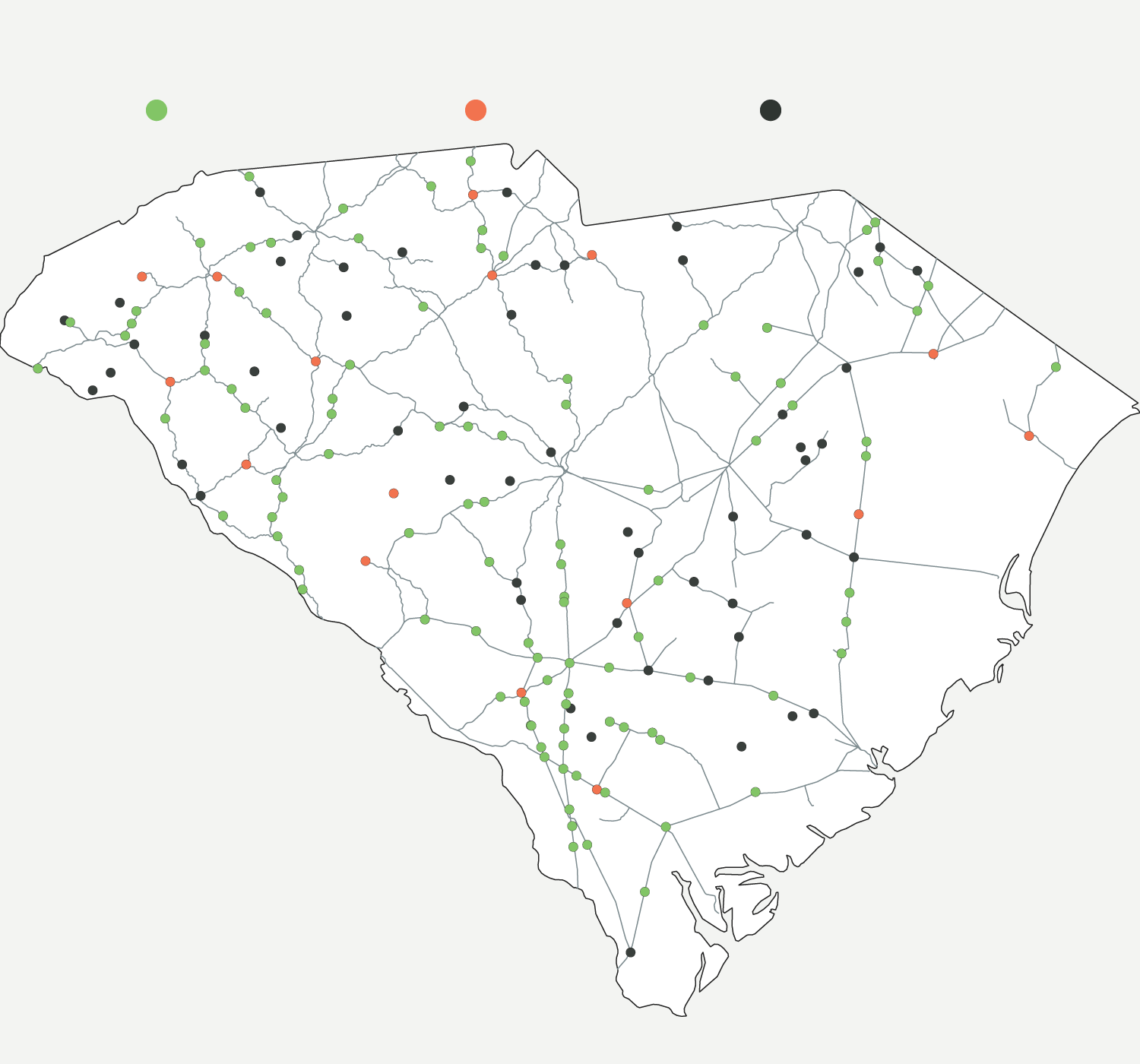

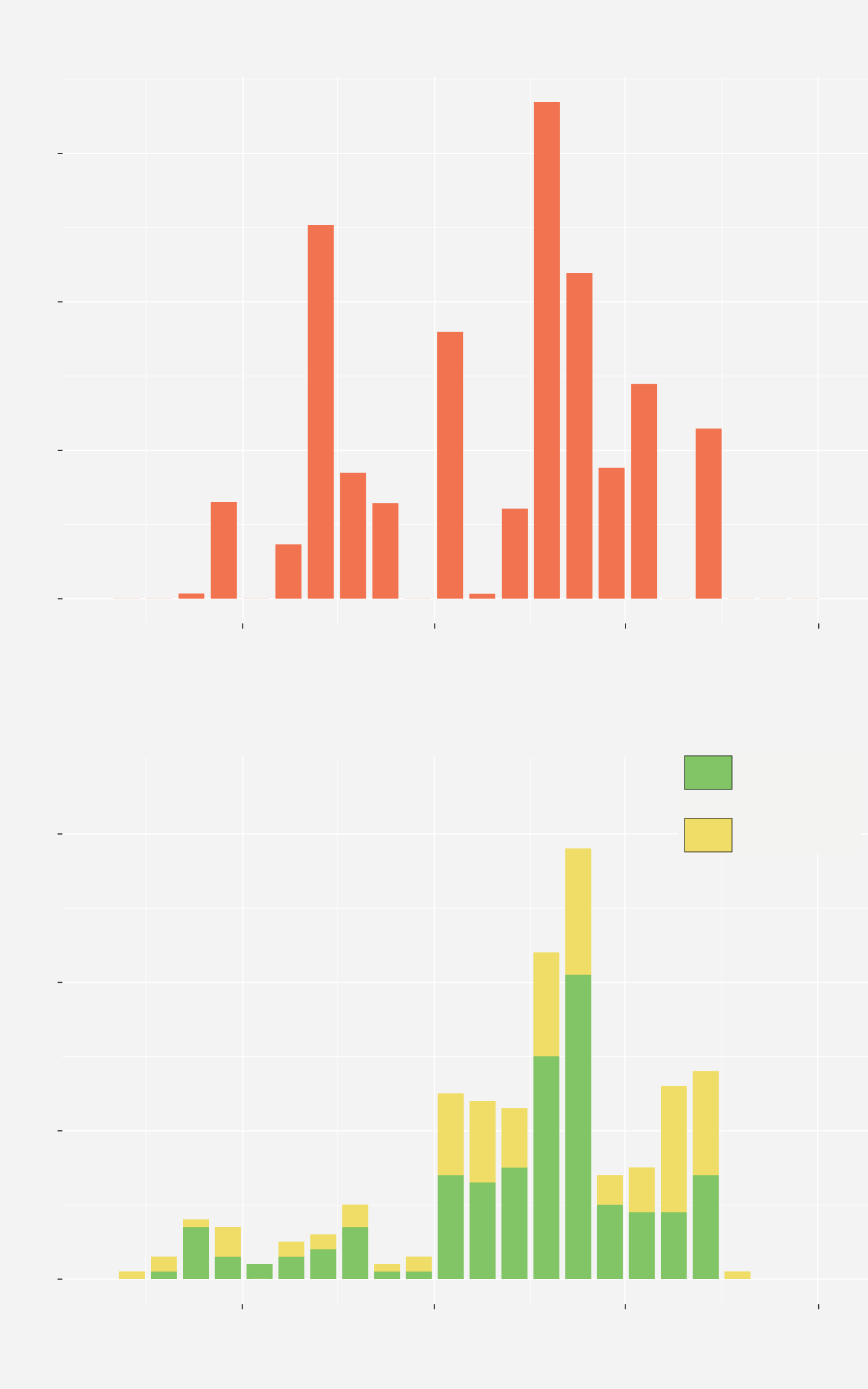

Railroad facilities are the most common center for circle towns

Types of structures recognized as center

Railroad depot or crossing

Courthouse

Other

*Data incomplete due to lack of information for some disincorporated towns

SOURCE: ANALYSIS BY THE POST AND COURIER

HONGYU LIU/STAFF

Boom of circle towns in the golden age of railroad

South Carolina was quick to embrace the emergence of railroads as drivers of transportation and commerce, and new lines soon spread across the state.

Among them, the 136-mile line from Charleston to Hamburg was said to be the longest in the world when it was completed in 1833. The new lines, along with others, would hasten the birth of circle towns across the state.

Aiken, incorporated in 1835, was among these new additions. The town was surveyed during the construction of the Charleston to Hamburg line. It took its name from William Aiken, president of the South Carolina Railroad Company. Unlike earlier circle towns, it recognized the railroad depot as its urban core.

After the General Assembly created a revolving fund to provide state aid for railroad construction in 1847, South Carolina experienced a “railroad mania,” as described by John McRae, a railroad engineer at the time. This allowed railroad companies to acquire rights of way with minimal or no costs. Total miles of rail line more than tripled over the next decade, and the state saw nearly 800 miles of new track being built in the 1880s alone.

Circular towns booming as new railroads opened in South Carolina

Miles of new railroads built in South Carolina

600

Miles of track built

400

200

0

1825

1840

1855

1870

1885

1900

1915

1930

SOURCE: VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY

New towns incorporated in South Carolina

Circular boundary towns

Non-circular boundary towns

60

50

Number of new towns incorporated

40

30

20

10

0

1825

1840

1855

1870

1885

1900

1915

1930

SOURCE: ANALYSIS BY THE POST AND COURIER

*All bars represent sum of every five years.

HONGYU LIU/STAFF

New towns sprung along the rail lines, with most placing a bullseye around their local depot to mark their centers. Of the nearly 200 towns incorporated between 1870 and 1900, 126 of them were formed as circles.

The Greenville and Columbia Railroad, completed in 1853, was the first to reach the Upstate. Along its route, the circle town of Williamston was incorporated in 1852 as a popular mineral springs resort in Anderson County. Less than 10 miles down the line, another circle town of Belton centered on the railroad depot after being incorporated in 1855 as a future junction. The village of Honea Path, initially a water stop for steam engines, was incorporated in 1855, also with a circular boundary.

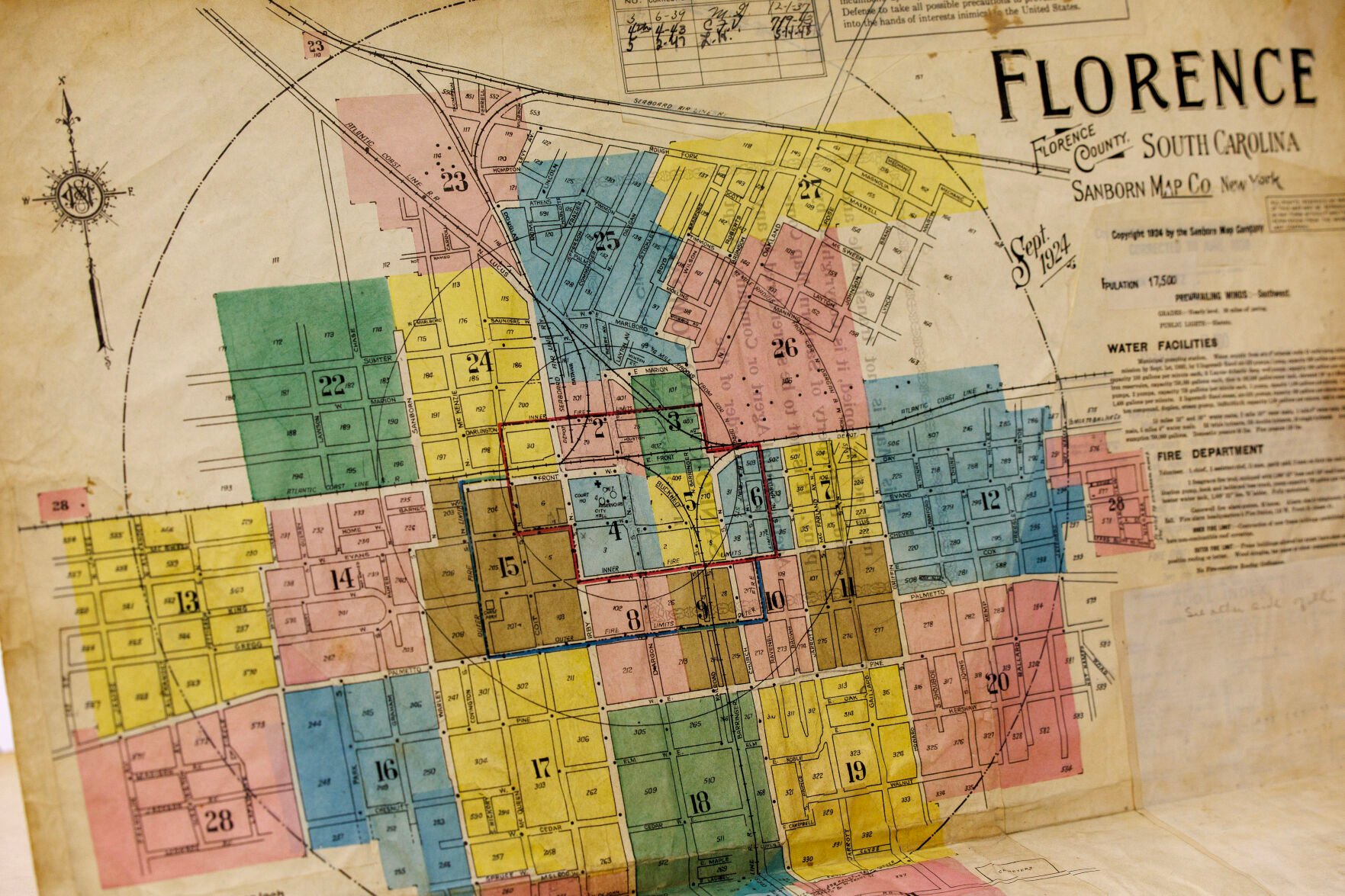

On the opposite side of the state, the city of Florence was planned as the junction for two major railroads completed around the 1850s: the Wilmington & Manchester and the Northeastern. Florence, named after the daughter of the president of W&M, was chartered in 1871 and later incorporated in 1890 as a circle town.

“People liked to call us the ‘Magic City’ as it seemed to come out of nowhere,” said Clint Moore, assistant city manager of Florence.

This unbridled growth came to an abrupt halt with the Panic of 1893, the most severe economic crisis before the Great Depression. It damaged the financial health of railroad companies nationwide. And, in turn, it put a marked crimp in the expansion of round towns whose fortunes closely followed the rails.

Circle towns enjoyed a brief resurgence due to an 1896 law that lowered the minimum population requirement for town incorporation from 1,000 to 200, enabling smaller communities to obtain charters.

But by 1912, the bump in bubble towns was over. No more communities would choose the so-called perfect shape to define themselves.

And things were about to get messy for the round towns that remained.

The disappearance of round towns

These days, it takes more than describing a set of lines on paper to create a town. Surveys, maps and blueprints replaced sentences, and modern geographic information systems have digitized municipal boundaries with uncanny precision since the 1980s.

No more would someone toss a brandy bottle onto a hill and count steps in all directions to see where the town’s boundaries lie. And if they did, they would find themselves some odd new corners along the way.

Over time, many of the original circle towns have acquired new land through annexation, looping a number of square parcels into the mix. In doing so, they eventually lost their roundness.

For some towns, the original centers have little to do with their modern identity, as development has drastically changed the surrounding landscape.

Florence has expanded significantly to the west – so far that its original circle appears like an odd attachment to its northeast corner. The Florence Mall and Magnolia Mall, located a few miles west of downtown, became the center for trading of the region due to their proximity to Interstate 95.

In the historical downtown, specifically the road junction of East N.B. Baroody and Dargan streets, which used to be considered the city center, now only marks the very end of a busy business district. The closed stores that pepper this intersection stand in stark contrast to the bustling restaurants and shops on Evans Street, just a few blocks down.

Some smaller circle towns have vanished from maps altogether as their charter expired or became invalid for various reasons.

Others, such as Laurens, soldier on with new borders that jut out in each direction. The county courthouse still stands at the original spot where the brandy bottle reportedly landed, surrounded by red-brick store fronts from the late 1800s. But its shape more closely resembles a splattered egg than a perfect sphere.

A Christmas tree lit up the town square on a recent evening. Add in some frosty precipitation and it could have passed for a scene from a snow globe.

Senn, the mayor, sees the storefronts and the town square as a gift that grew from the town’s circular shape. Through holding events in the square and renovating surrounding structures such as the Capitol Theatre, he hopes to make Laurens a walkable city with a strong community as its center.

“Nobody falls in love with a town because of its big box stores,” he said.

Residents shuffled in and out of storefronts and restaurants around him. Few seemed to realize that the town was once shaped like a globe. As with many round towns sprinkled across the state, that fact seems largely relegated to history books.

But those long-ago boundaries helped frame the stories of how these towns came to be and stood the test of time – closing a loop between past and present.

How we got our data

Obtaining a complete list of round towns can be arbitrary and subjective as maps were not widely used when many of these towns were incorporated. We used the “Towns of South Carolina,” a pamphlet published by the Research, Planning, and Development Board in 1947, as our reference on the name, county and date of incorporation for all towns that existed from colonial times to 1947.

We then studied the descriptions for town limits contained in the incorporation acts (for towns incorporated before 1896) or incorporation petitions (for 1896 and later). These files can be found at the S.C. Department of Archives and History. About 40 towns were dropped from our initial list during this step because the agency no longer kept their founding paperwork once they ceased to be incorporated.

To determine if a town has a round border, we looked for two main attributes in the language describing their boundaries:

- If the town recognizes a structure as its center and extends a certain distance from that point.

- If the description specifies that its shape is a circle.

This method leaves open a potential margin for error in the total count but represented the most reliable and accurate method based on available documentation.

Separately, the shapefile for historic railroads came from Jeremy Atack’s historical transportation shapefiles of Vanderbilt University.

–postandcourier.com