VIRGINIA: Recently Discovered Civil War Letters Trove May Be Largest Ever Found

RADFORD, Va. — Southwest Virginia gets limited respect in Civil War history circles, but a recently-discovered cache of letters tied to the Glencoe Mansion Museum may change that.

“In my experience, it is a unique collection,” Virginia Tech history professor emeritus William “Jack” Davis said of the letters. “And I use the word unique in its literal sense. I’ve never seen any other like it.”

Davis, 70, has studied the war for more than four decades. He is a former director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies and has continued to write and lecture about the conflict since his 2013 retirement from the university.

A portrait of Gen. Gabriel Wharton hangs in the home he built with his wife, Nannie Radford Wharton. It is unusual to find so many letters written by a woman during the Civil War, William C. “Jack” Davis said. Because they were carried by soldiers, they were often lost or damaged. But Wharton mailed his wife’s letters back to her, and she sewed the correspondence into books arranged in chronological order. They were stored in the Glencoe Mansion attic for more than a century, then moved to a garage in Florida for many years before Wharton descendant Sue Bell found them.

MATT GENTRY | The Roanoke Times

The collection may be the largest cache of Civil War correspondence found to date, Davis said. The more than 500 Glencoe letters were written between 1863-65 by Confederate Gen. Gabriel Wharton and Nannie Radford Wharton, a founding family of present-day Radford.

Discovered five years ago by Sue Bell, great-great granddaughter of the Whartons, the collection illustrates Civil War-era life in Radford and on the western battlefields of Virginia.

“To have virtually hundreds of letters from Nannie, written from Radford with some commentary on what life was like behind the lines through the war, and to have Gen. Wharton’s letters from … Narrows and Saltville and other such places that we don’t know a lot about really opens a window on a lot of … unappreciated history of the Civil War and of Virginia,” Davis said. “There’s nothing like it in my experience.”

No big battles were fought in the area, but the region provided iron, coal, salt, lead, rail transportation and more that kept the Confederacy going, Davis said. Protecting the region from Union forces was paramount because it was the geographic back door to the Confederate capital in Richmond.

Despite this, Southwest Virginia “hasn’t gotten very much attention either during the war or since,” Davis said.

At first, Bell said she began transcribing the letters as a family history project, but people kept telling her to publish them. So Bell went searching for a historian to help.

She found Davis.

For the past two years, the pair has worked transcribing and annotating the correspondence. They hope to publish the collection as early as 2019.

News from home

Gabriel Wharton, born in 1824 to a prosperous farming family in Culpeper County, graduated from Virginia Military Institute in 1847 and became a railroad engineer. He joined the Confederate Army in 1861 and spent much of the war commanding troops in Southwest Virginia.

Anne Rebecca “Nannie” Radford was born in 1843 to Dr. John and Elizabeth Radford, the family after which the city is named. Following the war, she would run businesses and write for her own newspaper.

Together, the couple would build Glencoe Mansion — today a museum, art gallery and visitor center — beginning in 1874.

Wharton met Radford sometime in 1862 on his way through “The Central,” as the city was then known, and despite a 20-year age difference, they were married the next year. They remained apart for most of the first two years of their marriage, and so began their voluminous correspondence.

“They wrote each other a letter almost every day during the rest of the war, sometimes two or three letters a day,” Davis said.

The early letters mostly show newlyweds getting to know one another.

“You could wish sometimes that there was a little more in his letters about what’s going on out on the battlefield,” Davis said. “He knows everybody, so he has dinner with Robert E. Lee and other famous generals. But about half of each letter is ‘Oh, I miss you so much, Nannie. Let’s get this war over with so we can be together forever.’ ”

But after a while, Bell said, the Whartons began to write more about their daily lives — he describing battles and military tactics, and she giving him career advice and even criticizing the leaders of the day.

“Nannie is not the quiet Southern woman you expect, that the books all say they are,” Bell said. “She is opinionated, educated. She’s only 19, but she is totally advising him.

“He’s only a colonel when they are married, and he’s waiting for his promotion,” Bell said of her grandfather. “She’s telling him: ‘I would advise you that if they offer you a regiment, that’s fine. But if they offer you a brigade, you should not accept it before you’ve gotten your promotion.’ ”

The young woman’s views of one now-venerated Confederate leader might be shocking to some.

“She thinks Robert E. Lee has a glorified reputation that he doesn’t deserve,” Davis said.

Bell said her grandmother was partial to Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

The Whartons also vent frustration with the course of the war.

“At a couple of points, they both talk about if things don’t get better, they’ll just leave the Confederacy and go abroad and suit themselves and to hell with the South, which is something you don’t often see,” Davis said. “[Nannie] is fairly pessimistic about the ultimate fate of the Confederacy. [Wharton] is quite the opposite.”

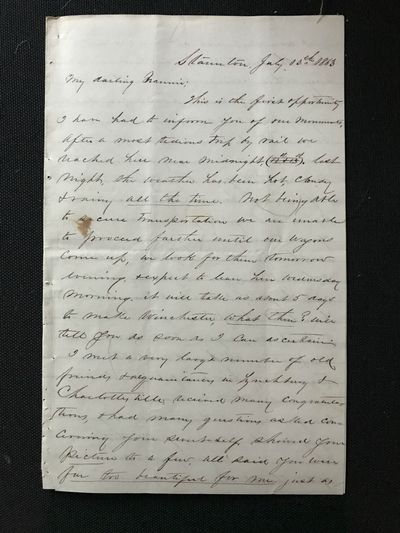

Photograph of an original letter from Gen. Gabriel Wharton to his wife, Nannie Radford Wharton. Sue Bell, great-great granddaughter of the Whartons, has spent the past five years transcribing more than 500 letters the couple exchanged between 1863-65.

Courtesy of Sue Bell

That Nannie Wharton’s letters exist at all makes this collection unusual.

“Typically, in Civil War correspondences, the woman’s letters tend not to survive because they get carried around in the campaign by the solider,” Davis said. “They get wet or read and re-read until they just fell apart. But he saved hers and sent them back to her.”

Nannie Wharton then arranged them in chronological order and literally sewed them together in packets. After the war, they were stored in the Glencoe attic and forgotten for more than a century.

Bell found them in her parents’ Florida garage, where they had been stored since 1981 — the year the family sold the historic mansion to Kollmorgen Corporation. That year, Bell and her mother, Sally Wharton van Solkema, cleaned out the house, which eventually would become a museum.

“I just remember my mother looking at the attic and saying, ‘I don’t know what’s up here, and I can’t throw it out,’ ” Bell recalled. They “threw everything into boxes, haphazardly.”

The mansion became a city museum in 1996.

In 2012, Bell decided to tackle the artifacts packed in the garage, and the task revived a long-buried impulse in the Virginia Tech alumna.

“I remember wanting to be a history major,” Bell said. “And my father said: ‘You’ve got to do something that will get you a job.’ ”

Bell majored in finance and French. She went on to work in computer consulting before raising four children.

After she found the letters, Bell sometimes spent hours a day reading, organizing and transcribing them while her kids were in school. Over the past five years, she estimates, she’s put in up to 20 hours a week on the project.

“It’s ironic; here I am writing a book about history, and that’s really what I had wanted to be,” Bell said. “I got to come full circle.”

People who saw the letters encouraged her to publish them, so she went looking for a historian to help. She found Davis, who unbeknownst to Bell, had searched for those letters 40 years ago.

Bringing the past to life

In the 1970s, Davis said he was researching a book on the Battle of New Market and tracing the descendants of men who fought there, including a Confederate brigade commander named Gabriel Wharton. Wharton had a grandson still living at Glencoe at the time, Davis said. But the descendant told him that the family had no documents.

Meanwhile, in the attic lay not just the Wharton letters but at least 1,000 other important documents, including letters to Wharton from many major Confederate generals of the day.

“A.P. Hill, James Von Street, John Cabell Breckinridge, P.T. Beauregard, Jubal Early — one famous Civil War personage after another,” Davis said.

Getting his hands on such a significant collection has been intoxicating for Davis. On a visit to Bell in Massachusetts, he sat, transfixed, for hours a time, she said.

“It’s the closest I think a historian can come to feeling like Christopher Columbus,” Davis said. “You’re hoping to find something like this for years and didn’t think it was there, and then, boom, it suddenly falls in your lap.”

For Bell, the project has literally brought history to life.

The family has always known that Gen. Wharton fought in the Civil War. Before finding the letters, it was a fact removed from daily life.

“It does make you feel more in touch with them,” Bell said. “These people, I hardly think that they’re dead because they feel so alive to me as I read all these letters.”

The tragedies feel fresh, and they prick compassion, not just for her own ancestors, but for the country.

“So many of Gen. Wharton’s friends were killed in the war,” she said. “Nannie lost two brothers.

“You think about what all these families had to go through, both North and South, … losing their kids, their cousins, their friends. You know, it’s just tragic,” Bell said. “And I don’t know if we can understand that now.”

Bell’s relationship to the museum dedicated to her family’s history has enriched its offerings. She said the family has donated some items, such as furniture. As she finds new information, Bell shares it with museum Director Scott Gardner.

“These were living, breathing people with strengths and faults,” Gardner wrote in an email. “The wealth of information we are learning is doing so much to teach us about the history of our region. … Every region has a unique role in history, and we want to openly portray to people what life was like in the late 19th century in Southwest Virginia.”

The Wharton papers offer a window not just on the war but on Reconstruction in the area and its effect on the family.

“They stay in Radford, and they set about trying to rebuild Southwest Virginia, which is fairly destroyed by the war,” Davis said. Gabriel Wharton “sets about trying to build railroads, factories and foundries.”

The general also served three terms in the Virginia House of Delegates, where he supported legislation that established the state’s land grant college in Southwest Virginia — despite efforts to put it near Richmond. Today that college has grown into Virginia Tech.

Nannie Wharton grew in influence after the war, too.

“She publishes and edits a newspaper, writing editorials about American foreign policy,” Davis said. “She runs a hotel for a time, takes some Radford family property and becomes a developer, dividing it into roads and home sites.”

She also ran the family’s 554-acre farm and a mill, Bell said.

But none of the Reconstruction material will go into the Civil War book, which by itself is more than 350,000 words, Davis said. Despite the size, several publishers are interested.

Davis said he could see several doctoral dissertations coming out of the Wharton collection that look at Reconstruction and beyond.

Bell said that she eventually will donate the entire Wharton artifact cache to an institution where scholars will have access to it.

–roanoke.com