The American Revolution (1775-1783), which pitted the powerful British empire against 13 upstart colonies, wasn’t just fought on the North American continent. The “shot heard round the world” in Concord, Massachusetts, also fired the political ambitions of other European colonial empires, drawing them into the struggle. Many of those ambitions played out in the Caribbean islands—which, far from floating offstage from the American conflict, served as an integral theater of the Revolutionary War.

Ever since Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in 1492, the cluster of islands south of America’s eastern coast had attracted European colonizers—Spanish, British, French and Dutch—eager to cultivate the valuable commodity of cane sugar. In 1776, Britain had several colonies in the Caribbean: Jamaica, Barbados, the Leeward Islands, Grenada and Tobago, St. Vincent and Dominica. The war offered Europe’s global powers the opportunity to potentially redraw their colonial maps by scooping up prized Caribbean territories, while knocking the British empire down a peg or two. The region also gave them a base from which to covertly influence the direction of the revolution, with the French and Dutch supplying money, artillery and gunpowder to the Americans by way of their Caribbean territories.

American rebels themselves also conducted war from the Caribbean. Colonial spies flitted from island to island, spreading propaganda and stoking disputes between Britain and its European enemies. By sea, American privateers wreaked havoc on British supply ships, diverting the empire’s military fleet away from the mainland. In fact, these sugar-producing islands became so economically and strategically important that, according to University of Virginia historian Andrew O’Shaughnessy, author of An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean, the British considered withdrawing from the North American conflict altogether to shore up the defenses of its island territories.

The Caribbean Becomes A Nest for Illicit Trade and Espionage

Early on, the French Caribbean territories of Martinique and Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) became crucial to the American war effort. Because Britain banned imports of artillery and powder to the colonies in 1774, the Continental Army was desperate for money and supplies during the war’s first year. The colonies’ only working gunpowder mill could barely sustain the rebels’ firepower needs.

In May 1776, sensing an opportunity to profit, French Foreign Minister Charles Gravier, comte de Vergenne, authorized the covert financing and supplying of American rebels with arms, money and even clothing. Prior to France’s official entrance into the war in 1778, it funneled these goods to American ports via merchant ships from Saint-Domingue and Martinique. It’s estimated the French provided 1.3 billion livres in credit and goods to American rebels.

Martinique also became a base of operations for American spies. One of the most famous, Philadelphia native William Bingham, worked there to cement friendly relations with the French, procure aid (often drawing on French credit arranged for by Benjamin Franklin) and support privateering activity against British ships. The Continental Congress had commissioned more than 2,000 of these freelance ship owners to divert British naval resources away from the mainland. Their strategy: target precious cargo-bearing ships from Britain’s island territories, causing them to need the British fleet’s protection. Thanks to Bingham, harbors in Martinique provided shelter for the booty acquired through privateering activity. And Bingham’s friendly ties with the French governor garnered valuable French maritime protection of goods and arms being ferried to American ports.

The tiny Dutch island of St. Eustatius, which measures only about 12 square miles, also played an outsized role in keeping the American militia armed. Though officially neutral in the conflict, the Dutch saw in the American Revolution an irresistible opportunity to fatten its coffers. In the early 1770s, roughly 2,000 American ships sailed to St. Eustatius annually to trade for sugar. In 1779, however, more than 3,500 American ships, many commissioned on behalf of the rebel government’s Committee of Secret Correspondence, made the journey to the tiny spit of land for stores of ammunition, arms and gunpowder cannily diverted from routes to Africa because of British blockades on European ports.

The illicit gunpowder trade not only amassed enormous profits for Dutch merchants—“in excess of 120 percent,” according to historian Victor Enthoven. Its success at helping keep the American infantry supplied with weapons caused the famous British admiral George Rodney to lament that tiny St. Eustatius “had done England more harm than all the arms of her most potent enemies and alone supported the infamous American rebellion.” After finally intercepting evidence on the illicit trade in 1780, the British officially declared war on the Dutch Republic that year, eventually seizing St. Eustatius.

The Caribbean Becomes a Naval Battleground

The French viewed the American war as an opportunity to regain some of its trade and maritime stature diminished by its stinging losses to the British during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). When France officially entered the American Revolution in 1778, it put greater strategic importance on consolidating its Caribbean holdings and picking off British territories than on engaging in conflict on the North American mainland, according to James Pritchard, former professor of history at Queens University, Ontario, in his article “French Strategy and the American Revolution: A Reappraisal.” And the French weren’t alone. In 1779, they lassoed Spain into the war by promising to support Spanish designs on valuable British territories such as Jamaica.

Having to defend its Caribbean possessions dealt a heavy blow to Britain’s plan to concentrate its forces on blockading the North American coast and countering the American insurgency. In December 1778, for instance, the British government siphoned 5,000 troops from New York to help capture the island of St. Lucia, a necessary venture for monitoring enemy activity in that crucial Caribbean rim.

Despite that win, the French, led by admirals such as Charles D’Estaing and François Joseph Paul, comte de Grasse, racked up a string of successes against the British navy. The French menaced British territories like St. Kitts and Barbados and ended up conquering islands such as Dominica (1778), St. Vincent (1799), Grenada (1799) and Tobago (1781).

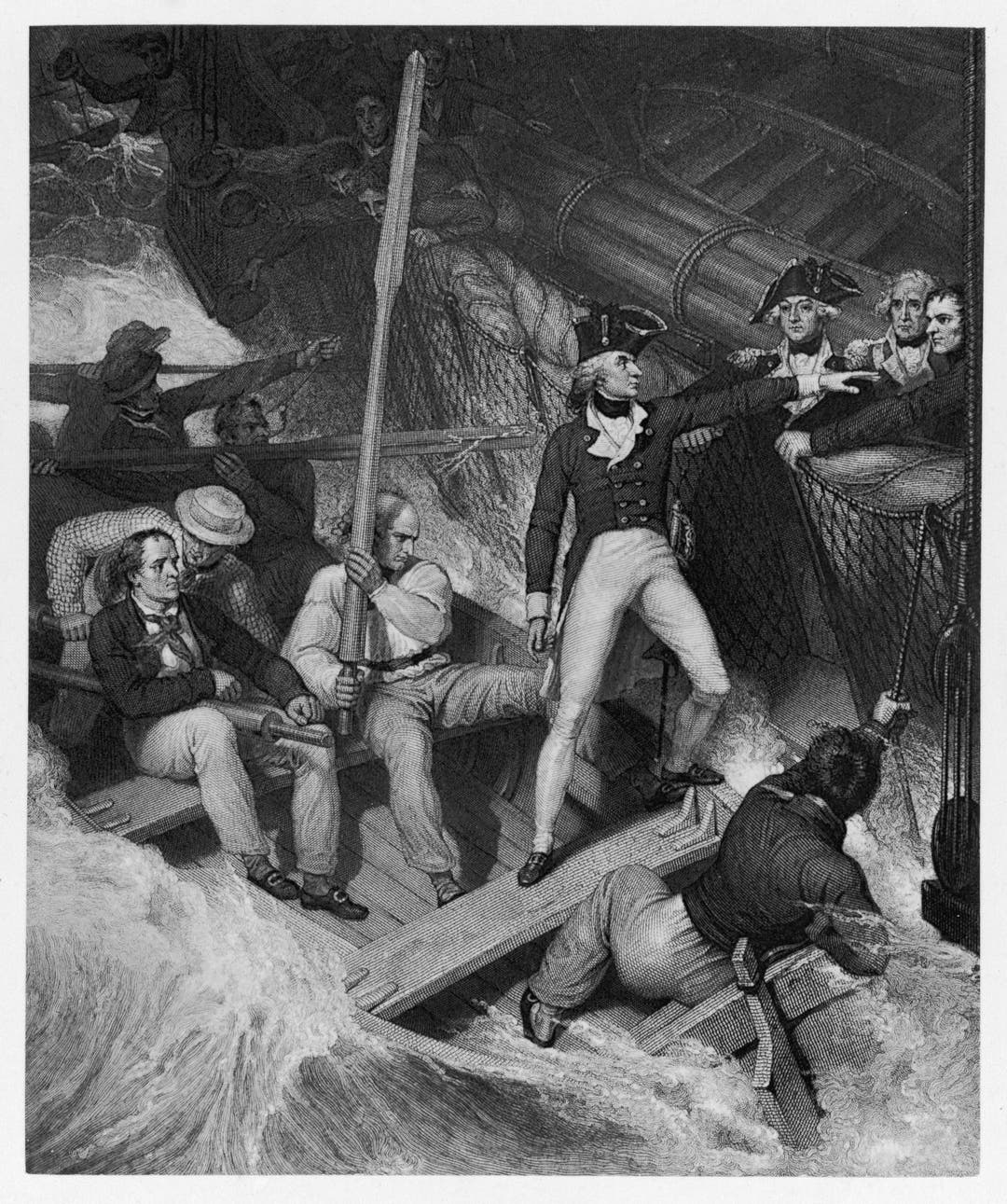

How a Rogue Navy of Private Ships Helped Win the American Revolution

When it came to waging war at sea during the American Revolution, the mighty British Navy had a vast advantage over its small and inexperienced colonial counterpart. But while the Continental fleet had little impact on the outcome of the war, tens of thousands of citizen sailors seeking both freedom and fortune played a critical, yet underappreciated, role in the quest for independence. An armada of more than 2,000 so-called privateers commissioned by both the Continental Congress and individual states preyed on enemy shipping on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, severely disrupting the British economy and turning British public opinion against the war.

In a tradition dating back to the Middle Ages, international law permitted countries at war to license private seamen to seize and plunder enemy vessels. While privateers differed from pirates in that they received legal authorization to operate through an official “letter of marque and reprisal,” the distinction meant little to those who encountered the marauders on the high seas.

Colonial Privateers Were Driven by Both Patriotism and Capitalism

Although the cash-strapped American colonies would never be able to challenge Britannia’s rule over the seas, they did have one advantage over their motherland. “[The British] have much more property to lose than we have,” quipped Declaration of Independence signer Robert Morris. Facing the impossibility of constructing a fleet to rival the world’s most powerful navy, the Continental Congress decided to authorize privateers as guerrilla-style disrupters.

During the siege of Boston at the onset of the American Revolution, George Washington had leased private ships and manned them with uniformed personnel. The Continental Congress went further in March 1776 by permitting private citizens “to fit out armed vessels to cruise on the Enemies of these United Colonies.” Privateers seeking commissions were required to post bonds of up to 5,000 pounds as collateral to ensure captives would not be mistreated and that they would not knowingly raid American or neutral ships.

While Washington offered the crews of his makeshift navy a one-third share of any goods they captured and sold, the Continental Congress appealed to the financial self-interest of the citizen seafarers by decreeing that privateer crews could keep all of their plunder. “That seed of financial incentive mixed with patriotic obligations awakened the independent spirit of capitalism,” says Robert H. Patton, author of Patriot Pirates: The Privateer War for Freedom and Fortune in the American Revolution.

The measure proved instantly popular as merchants, whalers and fishermen converted their vessels into makeshift warships. By May 1776, at least 100 New England privateers were plying the waters of the Caribbean. “Thousands of schemes for privateering are afloat in American imaginations,” wrote John Adams. According to the National Park Service, the Continental Congress issued approximately 1,700 letters of marque over the course of the war, and various American states issued hundreds more. Privateering proved so popular that the Continental Congress distributed preprinted, preauthorized commission forms with blank spaces for the entry of the names of ships, captains and owners.

The proliferation of privateers, however, infuriated Continental Navy commanders such as John Paul Jones. Not only did the reluctance of privateers to take enemy prisoners make it more difficult to negotiate swaps for the return of American sailors, but privateers lured many seamen away from the navy with the prospects of better pay, shorter enlistment periods and engagements with unarmed merchant ships instead of the fearsome warships of the Royal Navy.

Much like investors in the stock market, speculators made vast fortunes by buying shares in and bankrolling privateering enterprises. Ship owners and investors usually received half the value of seized goods, with the other half divided among privateering crews. “Fellows who would have cleaned my shoes five years ago have amassed fortunes and are riding in chariots,” noted New England aristocrat James Warren of those involved in privateering. Morris saw privateering as a numbers game that relied on volume. “One arrival will pay for two, three or four losses,” he wrote. “Therefore it’s best to keep doing something constantly.”

FEATURED

The Appalling Way the British Tried to Recruit Americans Away from Revolt

Patriots forced onto horrific British prison ships were presented with two options: turn traitor or die.

Read more about The Appalling Way the British Tried to Recruit Americans Away from Revolt

Dispatched in 1776 to French-owned Martinique, a hub of international commerce, to secure weapons for the Continental army, the future Continental Congress delegate and U.S. Senator William Bingham also solicited “private adventurers” of any nationality to raid British shipping. Privateering became so prevalent in the Caribbean that, at one point, 82 English ships were anchored at Saint-Pierre awaiting the sale of their pilfered goods—in some cases back to their original owners. Bingham’s cut on a single shipload of coffee and sugar exceed a quarter-million dollars in today’s terms, according to Patton, who writes that “Bingham’s privateering activities vaulted him into the financial stratosphere.”

Privateers Damaged the British Economically and Politically

Not only did American privateers’ hit-and-run attacks severely disrupt British commerce from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Caribbean Sea; they also operated close to British shores, even ambushing merchant ships in the English Channel. The result: Maritime insurance rates and the prices of imported goods in Britain began to soar.

Privateers’ success in looting and hijacking ships angered Britain’s wealthy merchants, as well as consumers facing higher costs. Denying the legitimacy of the Continental Congress or its right to license privateers under international law, many British lawmakers viewed the American commerce raiders no differently than pirates. Parliament passed the Pirate Act of 1777 that allowed American privateers to be held without trial and denied them the rights of prisoners of war, including the possibility of exchange. The measures spurred an anti-war movement among the segment of the British public that saw the country compromising its moral values in its treatment of enemy combatants and its decision to license its own privateers and revive the forced conscription of British citizens into the navy.

In the wake of the Pirate Act, the Royal Navy captured or destroyed hundreds of American privateers. Most of the 12,000 seamen who died in British prison ships during the war were privateers, and the losses left behind a generation of widows and orphans in some New England seaports. In Massachusetts, according to Patton, Newburyport lost 1,000 men in the destruction of 22 privateering vessels, while Gloucester lost all 24 of its registered privateers, cutting the population of adult males in half over the course of the war.

Still, despite the British crackdown, there were more than 100 privateer strikes in British waters in 1778 and more than 200 in 1779, according to James M. Volo’s Blue Water Patriots. This delighted Benjamin Franklin, who from his diplomatic post in Paris issued letters of marque to Irishmen sailing around the British Isles and encouraged American privateers to sell captured goods in French ports to create a diplomatic crisis between the British and the French. “Franklin used privateers to drive a rift between France and Britain, who had an uneasy peace,” says Patton. “The war was not really decided until France came into it, and Franklin’s manipulation of privateers was a huge element of that.”

While the Continental Navy captured almost 200 ships as prizes over the course of the war, Patton reports that privateers brought in 2,300, according to conservative estimates. “Privateers not only had an economic impact upon the enemy, but in the political sense they turned the tide of the civilian population in Britain against the war effort,” says Patton.

–history.com