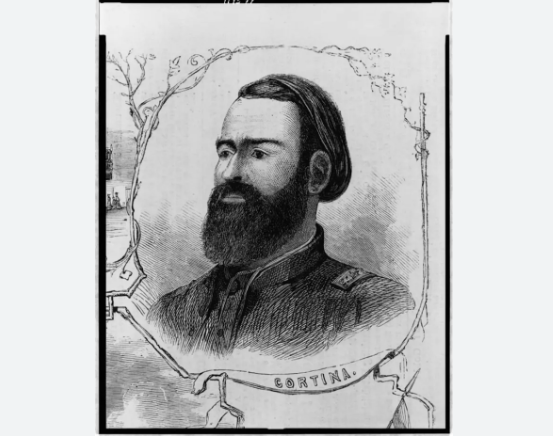

Juan Nepomuceno Cortina’s reputation as a Mexican bandit, murderer of U.S. citizens, and incessant raider won him heroic stature among Tejanos (Mexican-American residents of Texas). Yet his actions generated disdain from Americans nationwide from 1859 to 1877. He became the target of a joint civilian-military campaign along the Rio Grande, yet the Civil War and French intervention in Mexico made him an indispensable Federal ally.

Cortina’s family were long-tenured and wealthy inhabitants of the Rio Grande region. He was born in Camargo on the southern bank in 1824, yet possessed citizenship in both countries. Cortina served in the Mexican-American War as a scout in his home territory before experiencing fierce combat at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma as a cavalryman.

The cessation of hostilities brought Cortina’s home into Texan territory and American jurisdiction. Anglo-American settlers supplanted Hispanic culture in the borderland, and in response Cortina created a political resistance crusade called the Cortinista movement. The Cortinistas kept their composition a secret, standing on the principles of community aid and Hispanic unity. They sought to restore Tejanos’ socioeconomic standing and halt the seizure of their land. Their mission was to protect the impoverished through intimidation of unjust Anglo politicians and officials, and acts of cattle rustling and other thievery. Enthusiastic veterans lent their martial, spycraft, and guerilla experience to the cause.

Brownsville, Texas, rested on the border fronting the Mexican town of Matamoros across the river. Cortina moved to Brownsville in early adulthood and encountered ethnic tension over peonage laws and economic policies passed by the Texas state legislature, which impacted the livelihoods and civil rights of Mexican-Americans. Peonage was a form of debt bonded labor where an employee was compelled to work to pay off exploitative debts. Some acts restricted the ability of Tejanos from starting or operating businesses, or confiscated portions of their property. They were largely excluded from the societal upper class and positions of authority. On July 13, 1859, Cortina saw a Brownsville lawman physically abusing a Tejano laborer. Cortina demanded that the aggressor stop, and when he did not, Cortina shot him in the shoulder and fled across the river.

There, he assembled a seventy-man posse that attacked Brownsville on September 28. The town was defended only by local militia, and Cortina’s expedition quickly freed twelve Mexicans from prison and killed three allegedly corrupt Americans. The raiders raised the Mexican flag over the town and declared the formation of the Republic of the Rio Grande. At daybreak, representatives from the Mexican garrison at Matamoros met with Cortina. They informed him that his actions earned no support from their army, which was inclined to oppose him unless he left Brownsville immediately.

Cortina retired to the family ranch, yet maintained that he aimed to kill Anglo settlers harming Mexicans. At the ranch, he wrote two proclamations, the first addressed to Anglo Texans, specifically residents of Brownsville. Cortina assured law-abiding citizens that they had nothing to fear and explained the murder of the three officials. On September 30, the other letter, addressed to Mexicans in Texas appeared in a Brownsville newspaper. He addressed the Mexican residents, “Many of you have been robbed of your property, incarcerated, chased, murdered, and hunted like wild beasts…”[1]

Cortina characterized himself as a heroic figure who fought to help the less fortunate despite his banditry. Although he never used the Robin Hood analogy, modern scholarship identifies the mythical bandit as similar to how Cortina saw himself. Accounts from various sources differ as to the extent of his thievery. While there is no doubt of his prolific cattle rustling, some note he did not stoop to outright pillaging. After the Mexican-American War, Cortina saw the incorporation of Texas as led by immoral individuals and now wanted to endear commoners to his cause. Despite his fervent Mexican nationalism, Cortina continued to exercise his American citizenship and did not advocate for returning Texas to Mexico. Instead, he called upon U.S. state and federal officials to correct the injustice along the Rio Grande.

Mexican Gen. José María Jesús Carvajal sent a detachment of Matamoros militia who, alongside their American counterparts from Brownsville, attacked Cortina’s camp at Rancho del Carmen on October 24. The battle left only a few dead on either side, yet the Cortinistas captured two cannons, allowing them to claim victory. Soon, recruits poured into Cortina’s ranks, among them Tanpacuaze Indians, Mexican soldiers, and Hispanics living in Texas, all hoping to gain a more favorable status on the borderlands.

Further incursions into Texas horrified members of the American press, who misreported Cortina’s campaign as an attempt to wipe out Anglosettlers. Reports of John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in October 1859 drew editorialists to claim that Cortina worked with Brown and abolitionist factions from northern states to bring war to the South. Hardin R. Runnels, the lame-duck Texas governor, overheard a rumor that Cortina captured Corpus Christi and ordered the deployment of a company of Texas Rangers to apprehend him.

Major Samuel P. Heintzelman also took arms to pursue Cortina, his task force supplemented by additional Rangers. Heintzelman reached Brownsville on December 5 with a single company of U.S. cavalry under Capt. George M. Stoneman, sixty-six men of the First Artillery, and two companies of the First Infantry. Plans to dispatch more Army personnel were scrapped when it became apparent that the Cortinistas numbered only a few hundred. Heintzelman assumed overall command of the expedition, numbering around 150 Federals and 200 Texas Rangers, some of whom were equipped with privately purchased breech-loading Sharps carbines.

On December 27, the expedition advanced to Rio Grande City, where Cortina coordinated an intricate defense. Cortina protected his left and center with infantry and artillery, rested his right on the river, and kept a small cavalry force in reserve. One column of rangers was to attack from the rear, while one was attached to the right flank of the Federal force, which advanced directly on the main road with the artillery. The first column of rangers found most of the Cortinistas camped a half mile outside of the city and wound up attacking the camp head-on. Intense combat ensued, but when the Federal Army came into sight, the Cortinistas flew into retreat. A nine-mile pursuit ended with the regular troops capturing Cortina’s artillery pieces and supply wagons as his command dispersed into Mexico. This brief expedition demonstrated the possibilities of coordination between Federal and civilian troops. Texas Rangers displayed superior horsemanship and borderland experience in conjunction with the army’s logistics and firepower.

Cortina’s men fired from the Mexican side of the river toward a body of Texas Rangers on February 4, 1860. In response, forty-nine rangers crossed into the camp, killing twenty-nine and injuring forty. In the engagements and raids to this point, Heintzelman estimated that Cortina suffered 151 killed, compared to thirty-eight American combatants. Roughly eighty Hispanic and fifteen Anglo residents perished as well.

The search for Cortina continued as Stoneman engaged in a battle in Mexico on March 17 before discovering that he was fighting Mexican troops also looking for Cortina. Colonel Robert E. Lee attained authorization to pursue the raider and to do so into Mexico if necessary. Yet Lee recognized it would be impossible to catch Cortina without Mexican cooperation. On April 2, Lee issued a letter to the governor of the State of Tamaulipas, Andrés Treviño, demanding that Mexican authorities apprehend Cortina and any bandits planning to attack American territory. Treviño assented, and Mexican forces escalated their own campaign against Cortina, pushing him to flee into the mountains.

Upon reaching his San Antonio headquarters in May, Lee learned that Cortina had resumed his actions. The momentary cooperation between American and Mexican officials restored temporary order to the borderlands and seemed to promise continued relations. Yet the coming American Civil War and French occupation of Mexico in December 1861 reignited the lawlessness and bloodshed that gripped the region.

During the secession crisis and the Civil War, Cortina strongly supported the Union cause. Despite his recent clashes against the U.S. government, his lifelong tormentors donned the Confederate gray, and he foresaw Federal forces bringing stability and justice to the borderland. In April 1861, the residents of Zapata County, according to officials, voted unanimously to secede, yet Unionist support persisted. Antonio Ochoa, a Cortinista, gathered several fellow armed Union men who advanced upon Carrizo, the county seat. They sought to compel local authorities not to swear oaths to the Confederacy, and after tense negotiations, Ochoa’s men backed down. On May 22, Cortina assaulted a nearby Zapata ranch. Confederate soldiers from Fort McIntosh, commanded by Captain Santos Benevides, defeated the raiders in a forty-minute battle. The rebels forced the raiders back to Mexico and then executed eleven captives.

As the Civil War progressed into 1862, France, Spain, and England landed at Veracruz to coerce Mexican President Benito Juarez to repay his debts. The French revealed their intent on occupation, and the other European powers left. Cortina fought with Juarez against the French imperials, earning the rank of lieutenant colonel. North of the Rio Grande, his band harassed the Confederates by intercepting supplies and killing civil officials. When Federal forces captured Brownsville in 1863, Cortina cheered across the river and later hosted Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks in Matamoros. Several of his men joined the Union army, to which Cortina smuggled arms.

On September 6, 1864, Cortina dispatched 300 men, who, armed with three cannons joined forces with Federal troops and attacked Confederates near Palmito Ranch, losing twelve men captured. The rebels succeeded in forcing a Union retreat three days later, but the unprecedented fighting demonstrated Cortina’s support for the Union, soon to be returned in kind.

A French imperial advance resulted in the surrender of Matamoros, and Cortina briefly served in their army, possibly under duress. By April 1865, he returned to the Juarista forces and continued diplomatic relations with the United States. After the Civil War, he created a U.S. Army recruiting station in Brownsville. United States Army command turned its attention to the French intervention, and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman met with Cortina and began supplying the Juaristas. The last French forces evacuated Mexico on March 12, 1866. Five years later, Cortina found forty-one signatories, including a former Brownsville mayor, to sign a petition pardoning his crimes due to his service alongside the Union. The Texas legislature rejected the measure.

Cortina returned to his outlaw life, leading a group of cattle rustlers who raided Texan farms. Mexican authorities arrested him in Mexico City in 1877, and he languished in prison until 1894, released right before his death. Through his many escapades, he earned the moniker “Robin Hood of the Rio Grande.”[2]

Some historians argue whether Cortina truly acted for the benefit of the Tejano and Mexican commoners or if his actions were motivated by personal greed and revenge. The sustained chaos he maintained for nearly twenty years escalated ethnic tensions and incited violence toward those he purported to represent. His career spanned overlapping roles as a revolutionary, bandit, soldier in the Mexican and French armies, enemy and ally of U.S. forces, and experience as an occupier and victim of occupation.

The complicated figure of Juan Cortina enriched himself along the way, yet never faltered in his conviction to defeat the class of elite, prejudiced Texans who had wronged him initially. He left a legacy both as a folk hero and a villain; all that is certain today is that Juan Cortina is a legend along the borderlands.

Aaron Stoyack is a historian, museum specialist, and writer employed as a Park Ranger at Pamplin Historical Park. He graduated Summa Cum Laude from West Chester University with a B.A. in History and a Minor in Museum Studies. Aaron has served on local commissions and presented at regional and national public history and education conferences. He enjoys researching and interpreting all aspects of history, from local to global scale.

–emergingcivilwar.com

Bibliography

Cohen, Barry M. “The Texas-Mexico Border, 1858-1867: Along the Lower Rio Grande Valley During the Decade of the American Civil War and the French Intervention in Mexico.” In More Studies in Brownsville History, edited by Milo Kearney, 175-190. Brownsville: Pan American University at Brownsville, 1989. https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=regionalhist#page=186.

Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee: A Biography, Volume I. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934.

H.R. Exec. Doc. No. 52, pgs. 70-82. 36th Cong., 1st sess. (1860). https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2564&context=indianserialset.

Jennings, Nathan. “The Army’s Rio Grande Campaign of 1859: A Total Force Case Study.” In Infantry, Apr-Jun 2018. Fort Benning: United States Army Infantry School, 2018. https://www.moore.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2018/APR-JUN/PDF/11)Jennings-TotalForce_txt.pdf.

Johnson, Benjamin H. “Reconstructing North America: The Borderlands of Juan Cortina and Louis Riel in an Age of National Consolidation.” In Remaking North American Sovereignty: State Transformations in the 1860s, edited by Jewel L. Spangler and Frank Towers, 200-219. New York: Fordham University Press, 2020. https://ecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1089&context=history_facpubs.

“Juan Nepomuceno Cortina and the American Civil War.” The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.utrgv.edu/civilwar-trail/civil-war-trail/cortina-civil-war/index.htm.

“Juan Nepomuceno Cortina and the ‘Second Cortina War’”. The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.utrgv.edu/civilwar-trail/civil-war-trail/cortina-second-war/index.htm.

Larralde, Carlos. “Josiah Turner, Juan Cortina, and Carlos Esparza: Veterans of the Mexican War Along the Lower Rio Grande.” In Papers of the Second Palo Alto Conference, edited by Harriet Denise Joseph, Anthony K. Knopp, and Douglas A. Murphy, 119-127. Brownsville: Department of the Interior, 1997.

McCaslin, Richard B. “Rangers, ‘Rip’ Ford, and the Cortina War.” In Tracking the Texas Rangers: The Nineteenth Century, edited by Bruce A. Glasrud, 170-189. Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2012.

Rippy, J. Fred. “Some Precedents of the Pershing Expedition into Mexico.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 24, no. 4 (1921): 292-316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30234809.

Thompson, Jerry. Cortina: Defending the Mexican Name in Texas. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2007.

Weber, David J. Foreigners in Their Native Land: Historical Roots of the Mexican Americans. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1973.

Yanez, Edward. The Mexican Robin Hood: Antebellum-Era Texas Identity Politics. [Unpublished Bachelor’s Thesis] Wesleyan University, 2021. https://digitalcollections.wesleyan.edu/_flysystem/fedora/2023-03/24213-Original%20File.pdf.