The harlequin bug arrived in Texas in 1864, coinciding with increased Federal operations in the state. Earning nicknames such as the “Lincolnite” or “Sherman-bug,” its sudden appearance and proclivities appeared to make it the perfect weapon.[1] It feeds on the juices of various leafy greens, root vegetables, and fruit trees, propagates rapidly, and primarily ranges south of Philadelphia.[2] Attaining sustenance by sucking on the plant’s sap, it can destroy a crop quicker than devouring vegetation whole.[3] These attributes prompted Southerners to allege that Union agents deliberately spread the insect, the first time in history a government was denounced for using bugs to attack their adversary’s agriculture.[4] Its convenient appearance did little if anything to hamper the Confederate war effort, but there is no proof of a plot to deploy it. In fact, there appears to be no primary source evidence for accusations at all.

The above claim that Confederates accused the Yankees of intentionally planting the bug is repeated on popular history websites and in academic papers. These references stem from a single secondary source, by which the researcher can follow the chain of citations to find an original account if one exists. What began as an article about this potential weapon shifted focus due to the lack of contemporary records of the allegations. Before investigating the source’s primacy, it is logical to ground the occurrence with others from the historical record.

Entomological warfare refers to using insects against an enemy force to spread disease, cause pain and discomfort, or consume and destroy crops. Rarely applied in modern warfare, it is an effective tactic that provides plausible deniability for its user. Indeed, many allegations of its use are difficult to prove. Many countries conducted experiments in the 20th century, but only Imperial Japan is known to have used it in recent times. During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), they released crawling and flying beasts knowingly infected with deadly illnesses.[5]

The role of insects as a disease vector is well-known to any student of the Civil War. Union forces alone suffered 46,920 deaths from insect-borne diseases. If one includes dysentery, usually caused by impure water but which can be spread through bug bites, the number expands to 91,478.[6] Estimates place the Confederate death toll at well over 40,000.[7] Masses of men and animals, the waste they generated, stagnant water, and exposed food created prosperous breeding grounds for irritant and deadly insects. Soldiers frequently wrote about the volume and annoyance of these creatures, yet their ability to transport illnesses was poorly understood.[8]

Among the first accounts of using arthropods (invertebrates with exoskeletons and paired jointed appendages) on the battlefield dates to the years 198 and 199, when residents of a city in present-day Iraq flung pots full of scorpions at attacking Roman troops.[9] As one can imagine, the direct battlefield deployment of stinging insects was wholly impractical for a modern conflict such as the Civil War. Nevertheless, one industrious Georgia woman leveraged her rows of beehives against prospective Federal looters. She attached a rope to the hives, which she pulled to agitate the bees every time blue-clad soldiers approached. While an effective deterrent, her case stands isolated in instances of intentional insectile injuries.[10]

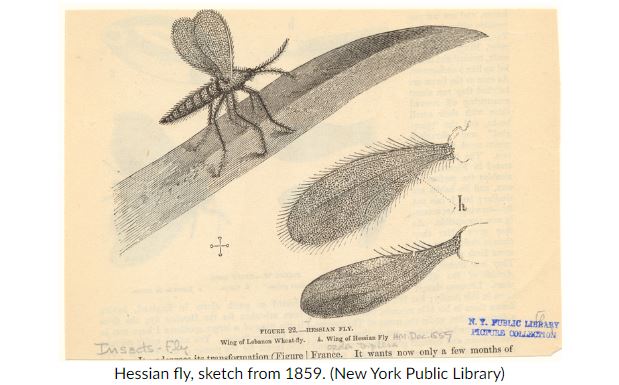

Accusations of six-legged sabotage occurred on the continent before the Civil War. The Hessian fly appeared in New York wheat fields in the late 1770s. No direct evidence linked the new arrivals with the German units hired by Britain to help suppress the rebellion. Yet patriots drew similarities between both foreign invaders. Americans mused that either the ungentlemanly Hessians intentionally imported the creatures to starve their adversary or the unclean nature of their transports and lifestyles created an atmosphere for the bugs to propagate.[11]

The infestation spread, and by 1788 lower-class farmers struggled to provide and survive with insufficient aid from their state or brand-new federal government.[12] The Hessian fly spread as far as Canada and the Upper South, contributing to large-scale devastation several more times during the early republic period.[13] Ultimately, the fly’s origin remains undetermined, with no concrete proof of it being spread by overseas trees and the possibility of it being a native animal that adapted to feed on wheat. The fly and its destruction were not forgotten, providing a basis of understanding that insects had the potential to harm an opponent’s food supply.

Turning again to the harlequin bug, the longstanding scholarly consensus is that it independently migrated north from Central America. Its habitat now extends as far as Colorado and Michigan, although it is only an endemic pest in southern states.[14] All proponents of the Civil War connection seem to cite a single source, “Entomological Warfare: History of the Use of Insects as Weapons of War,” a 1987 article from the American Entomologist. The author gleaned the claim from a 1962 edition of a 1928 book, Destructive and Useful Insects: Their Habits and Control.[15]

This, in turn, specifies a Department of Agriculture bulletin from 1920 informing farmers about methods to control the pest.[16] There is no reference to the Civil War therein, and the bulletin tracked the distribution from Washington County, Texas, in 1864 to Louisiana “a year or two later,” then North Carolina in 1867, and Missouri and Tennessee in 1870.[17] The harlequin bug’s potential for ruination is significant, but with its American range seemingly localized in Texas during the war, its outcome on the conflict, if any, would be negligible. With no references in the bulletin, the case for charges of entomological warfare appears unlikely.

Earlier publications similarly offer few leads. A 1915 Texas Agricultural Experiment Station pamphlet points closer to the report of the initial Texan discovery.[18] The 1908 print from the Bureau of Entomology appears to be the originator of the scientific claims, with most subsequent publications paraphrasing the text. Well-referenced for its time, it cataloged the source for the creature’s first account in America.[19] Dr. Gideon Lincecum publicized the animal in 1866, two years after its first appearance. Perhaps as expected, there is again no reference to its deliberate deployment or, indeed, to its supposed depredations during the war.[20]

Searches for all nicknames of the insect in newspapers, the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, and other letters reveal no references to the invader whatsoever. Several cliches, such as ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,’ come to mind. It is not unfeasible that an account exists somewhere condemning the Yankees for entomological warfare. Either way, the chain of provenance for the claim is fractured. The earliest mention dates over sixty years after the war in a scientific rather than historical work. It is the duty of the historian to search for and interpret firsthand accounts whenever possible. The dissemination of this undetermined fact results from various researchers neglecting further investigation. Such a mighty claim as the Civil War featuring the first accusations of entomological warfare against crops now seems tenuous.

Aaron Stoyack is a public historian, museum specialist and writer employed as a Park Ranger at Pamplin Historical Park. He graduated Summa Cum Laude from West Chester University with a B.A. in History and a Minor in Museum Studies. Aaron has served on local commissions and presented at regional and national public history and education conferences. He enjoys researching and interpreting all aspects of history, from local to global in scale.

Endnotes:

[1] John L. Capinera, “Harlequin Bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae),” in Encyclopedia of Entomology (Berlin: Springer, 2008), 1766-1768. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_1264.

[2] Jeffrey A. Lockwood, Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 75.

[3] “harlequin bug – Murgantia histrionica,” Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida, 2015, https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/veg/leaf/harlequin_bug.HTM.

[4] Jeffrey A. Lockwood, Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 75.

[5]Dominik Juling, “Future Bioterror and Biowarfare Threats for NATO’s Armed Forces Until 2030,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 14, no. 1 (2023), 135-136.

[6] Joseph K. Barnes, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 1, Part 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870), data compiled by Robert K. D. Peterson, “Diseases of Entomological Importance,” Insects, Disease and History, Montana State University, accessed September 1, 2024, https://www.montana.edu/historybug/civil_war_disease_table.html.

[7] Lockwood, Six-Legged Soldiers, 66-68.

[8]Gary L. Miller, “Historical Natural History: Insects and the Civil War,” American Entomologist 43, no. 4 (1997): 229. https://www.battlefields.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/historical-natural-history-insects-civil-war.pdf.

[9]Adrienne Mayor, Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World (New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2009), 127-129.

[10] Gary L. Miller, “Historical Natural History: Insects and the Civil War,” reprinted and adapted from American Entomologist 43, no. 4 (1997): 227-245. https://www.montana.edu/historybug/civilwar2/buzz.html.

[11] Philip J. Pauly, “Fighting the Hessian Fly: American and British Responses to Insect Invasion; 1776-1789,” Environmental History 7, no. 3 (2007): 490-492.

[12] Alan Taylor, Continental Revolutions (New York: Norton & Company, 2016), 327.

[13]Lucia C. Stanton, “Analyzing Atoms of Life,” Monticello Keepsake 50 (1991). https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/hessian-fly/

[14] Capinera 1776-1778.

[15] Jeffrey A. Lockwood, “Entomological Warfare: History of the Use of Insects as Weapons of War,” American Entomologist 33 no. 2 (1987): 1.

[16] Clell Lee Metcalf, Wesley Pillsbury Flint, Destructive and Useful Insects: Their Habits and Control (New York: Mcraw-Hill, 1928): 503.

[17] F.H. Chittenden, “Harlequin Cabbage Bug And Its Control,” Farmer’s Bulletin 1061 (1920): 5.

[18] F. B. Paddock, “The Harlequin Cabbage-Bug,” Texas Agricultural Experiment Station 179 (1915): 3.

[19] F.H. Chittenden, “The Harlequin Cabbage Bug,” Bureau of Entomology, Department of Agriculture 103 (1908): 3.

[20] Gideon Lincecum, “The Texan Cabbage-Bug,” The Practical Entomologist 1, no. 11 (1866): 110. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/53045.

–emergingcivilwar.com