History never remembers who the quartermasters were: That was Nathanael Greene’s retort when George Washington pressed on him the job of quartermaster of the Continental Army in 1778. And though Greene yielded to Washington’s plea, he was right. Despite doing a near-miraculous job in rebuilding the fragile supply network of the American Revolution, he is most remembered for his handling of Continental troops in the battle at Guilford Court House in North Carolina in 1781, the set-piece of Mel Gibson’s movie “The Patriot.”

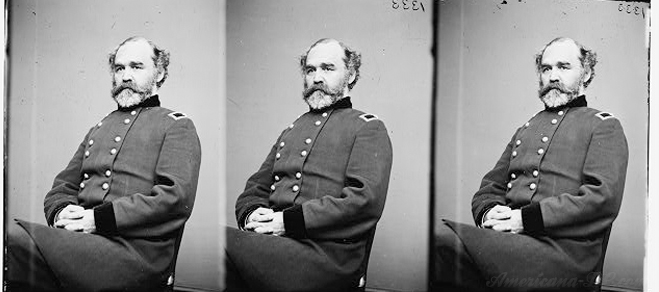

The same rule applies to the Civil War. The name of Montgomery Cunningham Meigs is today likely to show up only in Civil War versions of “Jeopardy!” as a late-round stumper. Meigs was, after all, only the quartermaster general of the U.S. Army from the outbreak of the Civil War until his retirement in 1882. Still, the fighting end of war tends to go badly unless the business end is rightly managed. Grant and Sherman might have won the battles, but they could not have done so without Meigs.

Curiously, Meigs came into the job of the nation’s military supplier with no prior experience in business. He was the son of a Philadelphia physician and graduated from West Point. His high class standing there earned him a commission in the coveted Corps of Engineers, which meant that he spent his first decade and a half in the Army supervising construction projects and dredging rivers and harbors.

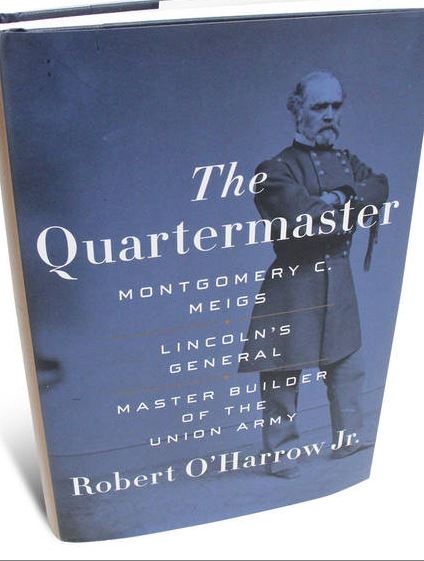

His mentor in the Corps, Joseph Totten, was responsible for his breakthrough assignment in 1852—to build an aqueduct to bring fresh water to Washington, D.C. He was not finished with that project before he was handed an even bigger one, rebuilding the Capitol dome. He succeeded in combining the high artistry of an architect with the nose-down application of the office toiler—which, together, made Meigs the available man when Abraham Lincoln needed a quartermaster general for the Union armies at the outbreak of the Civil War. Robert O’Harrow Jr.’s “The Quartermaster” is the lively story of the Civil War’s most unlikely—and most uncelebrated—genius.

Mr. O’Harrow is a staff reporter with the Washington Post, where his specialty has long been reporting on federal contracting. This makes him an ideal teller of Meigs’s story, since so much of Meigs’s life was bound up with the ins-and-outs of contract and supply. For the Post, Mr. O’Harrow often finds himself chronicling fraud and bid rigging. Not so with Meigs, who was the straightest of straight arrows and, as Mr. O’Harrow concedes, something of a prig. Meigs was “short-tempered” and “rigid,” with all the appeal of “an irritable, burly accountant whose battles were mostly with his ledgers and meddlesome politicians.” But he was also “a mix of hard work, ingenuity and inspired logistics” and well-suited to grapple with the massive increase in government spending triggered by the Civil War.

Meigs was appointed quartermaster general in June 1861. During the preceding fiscal year, the U.S. government devoted only $29.7 million to the combined military—Army and Navy. Meigs’s entire staff consisted of 13 clerks. By 1865, the federal budget had swollen well more than 25-fold to $1.9 billion, with $1.1 billion spent on the war. By then, the Quartermaster Department had a Washington-based staff of 591 people, not to mention more than 100,000 civilian personnel.

Not only were the opportunities for graft and enrichment legion in such an environment, but the demands for delivery of indispensable goods like tents, blankets, mess gear, horses, mules and wagons made time rather than cost the most important consideration. A government officer with just a shade less puritanical integrity than Meigs could have made a mint for himself and his cronies, with the needs of the soldiers in the field coming a distant second.

Not Meigs. In 1864 alone he was responsible for providing the armies with 200,000 blankets, 113,684 horses and 87,791 mules (and 400 tons of forage for them every day), as well as hundreds of gunboats steamers, sailing vessels and barges—not to mention boots and shoes and other essential supplies. The U.S. Military Telegraph system strung 15,389 miles of wire and employed 1,500 linemen and operators, all under Meigs’s oversight. During Ulysses Grant’s Overland Campaign in 1864, Meigs kept the Army rolling on 4,300 wagons, 30,000 horses and 23,000 mules. When Sherman’s army marched across Georgia to Savannah, Meigs was waiting at the coast with a complete refit for all of Sherman’s troops. Yet when Meigs’s books were audited at the end of the war, every expenditure, according to Rep. James Blaine, was “accurately vouched and accounted for to the last cent.”

Mr. O’Harrow’s account is short and breezy, relying mostly on the published volumes of Meigs’s journals and the Civil War Official Records, with an occasional dip into Meigs’s papers at the Library of Congress. It will not displace Russell Weigley’s more thorough but more stodgy 1959 biography of Meigs, and it shares with Weigley’s biography a surprising absence of attention to the actual practices of wartime contracting. Nor does Mr. O’Harrow spend much time on how Meigs managed the vast network of subordinate quartermaster officers assigned to each corps, division, brigade and regiment of the Union armies.

Mr. O’Harrow also misses one of the more startling conclusions that Meigs’s tenure as quartermaster general offers—that he handled nearly all of the government’s supply needs through private contractors. Only when it came to organizing a military railroad system did Meigs substitute direct government intervention for the free market. This practice stands in contrast with that of the Confederacy, which preferred to nationalize industries, transport and suppliers, with the result that its armies went to war poorly clad, poorly equipped and hungry. Meigs can be remembered as an unusual soldier with an unusual contribution to make to Union victory in the Civil War, but he might also be remembered as a very unusual American entrepreneur.

Mr. Guelzo is the author of “Gettysburg: The Last Invasion.”

–wsj.com