KENTUCKY: Where Are Kentucky’s Confederate Statues?

On the grassy lawn outside the Anderson County courthouse, along with monuments honoring Anderson countians who served in World War I, World War II and the Mexican-American War, stands a marble statue of a Confederate soldier.

The mustached man wears a broad-brimmed hat and holds his rifle in his hand. The stone base on which he stands is inscribed with the names of dozens of men who died or were injured while serving with the Confederacy in the Civil War.

The base of the Confederate statue outside the Anderson County Courthouse lists the names of Confederate soldiers who were injured or died during the Civil War. Other markers in front of the courthouse honor those who served in the Mexican-American War, World War I and World War II. Karla Ward kward1@herald-leader.com

“It is the county’s statue,” said Lawrenceburg Mayor Robert Goodlett. “I grew up here and it was just there all the time.”

Anderson County First District Magistrate Rodney Durr said he has not heard any local concerns about the statue.

Likewise, Jessamine County Judge-Executive David West said he has heard no complaints about Jessamine County’s bronze Confederate statue, which was dedicated in 1896.

“You couldn’t find two people out of 10 that would know what that was,” West said. “I think that’s probably because it’s not a (specific) person who participated.”

The statue in Nicholasville was one of many mass produced at Louisville’s Muldoon Monument Co., said Anne Marshall, a Lexington native who is an associate professor of history at Mississippi State University.

Interestingly, she said it was originally commissioned by a locale that wanted a Union soldier, but when that buyer backed out, the figure’s belt buckle was recast to say “CSA,” for Confederate States Army.

The statue honors “Our Confederate Dead” and bears an inscription on the front that says, “Who they were few may know, What they were all know.”

Rather than focusing on the Confederate marker, West said Jessamine County is choosing to highlight Camp Nelson Civil War Heritage Park, which has been designated a National Historic Landmark. It was the Union’s third-largest recruitment and training center for black troops, and more than 10,000 trained there, often accompanied by their families.

Barren, Calloway, Caldwell, Daviess, Graves and Hopkins counties also have Confederate statues and monuments outside their courthouses.

In most of those places, there appears to have been little recent discussion about the markers.

Two exceptions are Daviess County, where officials are considering whether to move their statue, and McCracken County, where the future of a statue in Paducah’s Fountain Square has become a matter of public debate.

In Danville, a statue of Confederate Capt. Robert D. Logan that was dedicated in 1910 stands adjacent to a historic Presbyterian Church on Main Street.

As is common, the base says the monument was erected “to the Confederate dead” by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and veterans of Boyle County.

The UDC was responsible for spearheading many of the campaigns to erect such monuments between 1895 and the 1920s, Marshall said.

Marshall, the author of Creating a Confederate Kentucky, said such monuments are the last, most visible, reminder of a celebration of “the Lost Cause.”

Marshall said the UDC worked to make sure history books didn’t have a bias against the Southern interpretation of the Civil War and succeeded in getting a state statute passed that banned the performance of “racially incendiary” plays such as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” a popular traveling show at the time.

For a while, she said, the Fayette County courthouse had a “Confederate Room” where groups like the UDC met.

“This monument stuff is just what we see today,” she said. “That was just one piece of this Lost Cause puzzle.”

In Kentucky, there are many more Confederate monuments than those honoring the Union cause.

Perryville Battlefield State Historic Site and Butler County’s courthouse are among the few places in the state where both Union and Confederate soldiers are memorialized.

State historian James Klotter, a professor of history at Georgetown College, said that as the Civil War dragged on, Kentuckians grew weary of Union occupation and became more sympathetic to the Confederacy.

After the war, he said, “they joined the defeated side.”

For years, he said, Kentucky’s Democratic party was dominated by former Confederates, and all of Kentucky’s governors until 1895 were Confederate sympathizers.

“Kentucky was very much like a Southern state in its racial views,” he said.

Now, he said, “it’s a different time and a different state and a different mindset.”

“It’s hard to find a compromise that everybody can agree with,” Klotter said.

Many people hold the monuments dear for a variety of reasons.

An online petition was created on Change.org last year by “Kentuckians for Kentucky Values” in an effort “to preserve all monuments of every war, especially Union, and Confederate.” More than 20,000 people have signed the petition, which is addressed to Gov. Matt Bevin.

Klotter and others said it’s important to try to find a way of bringing peace to all involved.

“People were complaining about it before, but we ignored them,” said Brian McKnight, a professor of history at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise. “Whites ignored that kind of complaint. Black people knew better than to complain.”

Last year, the Southern Poverty Law Center compiled a list of more than 1,500 public symbols of the Confederacy throughout the country. While the monuments, road names and other public Confederate references are concentrated in the deep South, about 40 are in Kentucky.

The statues of John Hunt Morgan and John C. Breckinridge at the old Fayette County courthouse building of course made the list, along with the statue of Jefferson Davis that stands in the state capitol building.

And then there is the Jefferson Davis State Historic Site, a state park outside Hopkinsville that marks the birthplace of Davis with a 351-foot obelisk.

In Central Kentucky, monuments honoring Confederate soldiers are located in cemeteries in Georgetown, Versailles, Cynthiana and Mount Sterling. A monument in Eminence marks the resting place of Confederate soldiers who were executed by the Union.

The Unknown Confederate Dead Monument erected in a private cemetery in Perryville is also on the list. It marks the site on private land where an unknown number of Confederate soldiers who died at the Battle of Perryville were buried.

McKnight said it’s important to consider the context in which each Confederate memorial was erected.

“You’ve got to figure out if the Confederate monument symbolizes the cause or the people who died,” he said.

WEST VIRGINIA: History Meets Beauty at Harper’s Ferry

The view from the top was more incredible than I ever could have imagined.

I was standing at Jefferson Rock in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. That point is one of the best spots to see the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. I also stood on a portion of the Appalachian Trail, which is another pursuit on my adventure bucket list.

Harper’s Ferry was the site of the infamous raid by abolitionist John Brown and a Civil War battle in 1862.

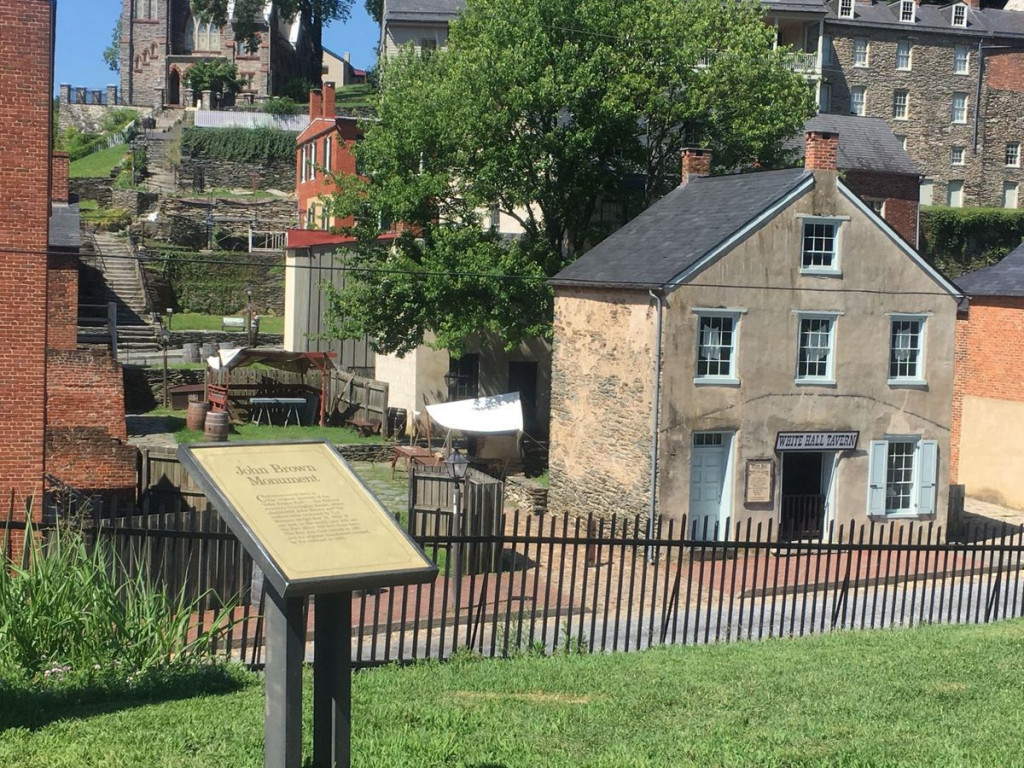

There is nothing quite as breathtaking as the Blue Ridge Mountains where Harpers Ferry National Historical Park is located. There is a visitors center, and shuttle buses take you to what is called Lower Town, which has the fort and armory site, period shops, films, exhibits and restaurants in the historic buildings.

This obviously is a special edition to a regular Cruisin’ column because Harpers Ferry is about a five-hour drive from our area. The trip also included Antietam, the site of a 12-hour battle in 1862, the bloodiest one-day confrontation of the Civil War. The Battle of Antietam killed 7,650 soldiers.

Harpers Ferry remains much as it did years ago. Robert Harper started a ferry across the Potomac here in 1747. By the early 1800s, the rivers powered the armory complex and commercial mills.

It’s a sleepy little community that thrives especially on the weekends when kayakers, rafters, hikers, historical buffs, sightseers and school groups descend. Parking is limited. That’s why it’s best to shuttle in.

But the name is probably most associated with a man named John Brown. An early abolitionist, he was determined, along with followers, to arm enslaved people and spark rebellion. His group seized the armory but the raid failed. Brown was tried and executed, which focused attention on the issue of slavery and propelled the nation toward civil war. Brown’s fort stands near its original location and the John Brown Museum is not far from there.

The valley town is snuggled in by mountains on either side. The train station is on one side of the village and is used by many who commute to the Washington, D.C. area.

From the point where the two rivers meet, we rested from walking and met many people. Some were walking the Appalachian Trail. Another group from Butler had taken the Capitol Limited from D.C. and biked 60 miles to Harpers Ferry. The next day, they traversed the footbridge to the C&O Canal, through a tunnel and up the side of a mountain to Maryland Heights, which took three and a half hours.

The homes and buildings are in themselves, historic and impressive. Many are built from stone and a few were repurposed into restaurants and taverns. Equally imposing is St. Peter’s Catholic Church, which is about the halfway point to Jefferson Rock. Built of stone, it features spires and stained glass windows.

The visit also included a dry goods store where there are guides dressed in period costumes offering information.

It’s definitely where the past meets the present.

At Antietam, we took the self-guided tour, starting at Dunkers Church. Fighting took place all around that small brick place of worship. We walked the Sunken Road also known as Bloody Lane where 2,200 Confederates fought 10,000 Union soldiers, finally collapsing after suffering too many casualties.

This day at the Lower Bridge, where water enthusiasts casually floated by with onlookers above, it was hard to believe that such a peaceful spot was once the scene of such violence.

West Virginia and Maryland are lovely states. Beyond history, there is so much to do in this beautiful part of the country.

The vistas and the natural settings, in themselves, are rewarding.

###