People on a VIP observation boat watch as the Confederate submarine Hunley is raised on Aug. 8, 2000. File/Brad Nettles/Staff

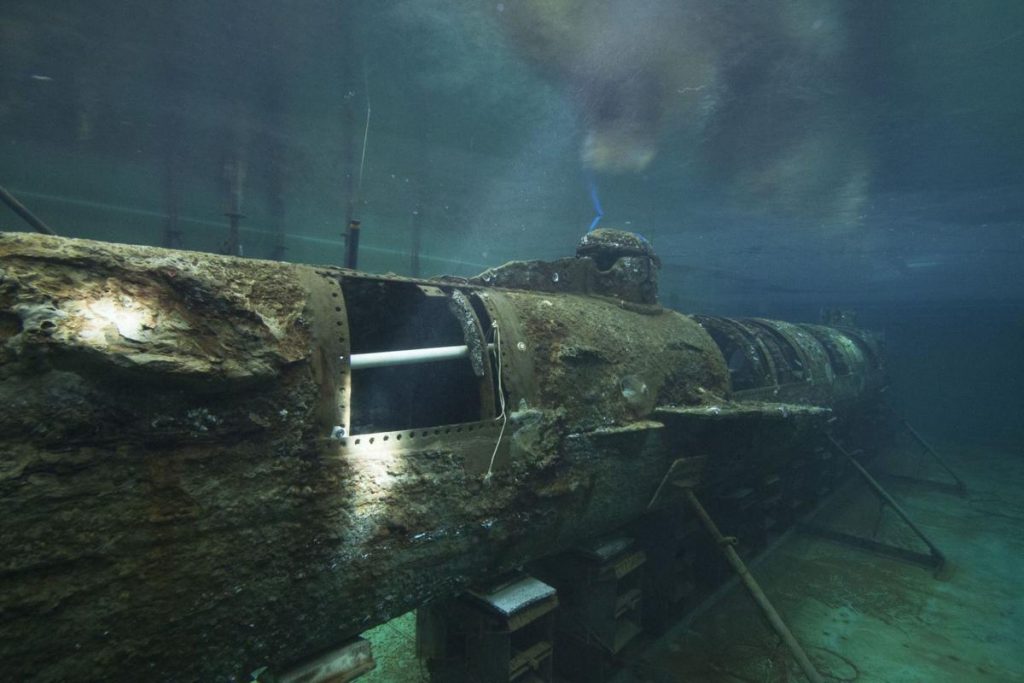

The barnacle-encrusted metal cylinder had languished in mud, seawater and sand for nearly 140 years.

But on Aug. 8, 2000, after decades of research, dives and study, a series of cranes pulled the H.L. Hunley submarine off of Sullivan’s Island to an audience of hundreds in person and thousands more watching TV across the country.

Kayakers treaded water to watch the vessel crest out of the ocean. Pedestrians on the aircraft carrier Yorktown watched through binoculars as it was barged through Charleston Harbor into the air. A boat was filled with reporters who watched and scribbled furiously as history was revealed before their eyes.

When the Confederate submarine was raised from the waters, it was classified by William Dudley, then the director of the Naval Historical Center, as “probably the most important find of the century.”

Kellen Butler, executive director of the Friends of the Hunley, describes the recovery as a flashbulb moment, a significant event that is shared in the collective memory of many.

“We were all kind of blown away,” she said. “If you were here in 2000, you know where you were that day the Hunley was raised.”

But a lot has changed in the 20 years since the first successful combat submarine was recovered from the depths. Charleston County has nearly doubled in population in that time. Some newcomers know the Hunley as a sandwich at some area restaurants, but couldn’t tell you where the sub is located.

The Hunley was the precursor to submarine warfare. Everything from the U-Boats of Nazi Germany to Tom Clancy’s “Hunt For Red October” starts with the first successful combat mission during the Civil War.

And while the discovery of the submarine was revolutionary for the history and military communities, it faces an uncertain future. A final resting place and a permanent museum has been discussed for more than a decade, and some worry that interest in the artifact is starting to fade.

Since the recovery, the sub has been undergoing conservation work at the Clemson University-run Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston on the grounds of the former Naval Base and Shipyard. The lab is open for tours on weekends.

A crowd watches the Hunley as it is raised to be placed in its tank at the Warren P. Lasch Conservation Center in 2008. File/Staff

At first, North Charleston agreed to become the future site of the Hunley Museum in 2004 by pledging $13 million toward creating a showplace for the Confederate submarine, but the city later withdrew the promise of funding. Work to restore and preserve the vessel continues.

Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant has been eyed as a final home for the submarine, but no major movement has happened.

Ralph Wilbanks, leader of the Clive Cussler dive team that found the H.L. Hunley, has been discouraged by the lack of progress.

“The public has lost interest, and you have to strike when the iron is hot,” he said. “The Hunley is a unique thing to Charleston, but it has national and worldwide significance. It really needs to be in a place like the Smithsonian.”

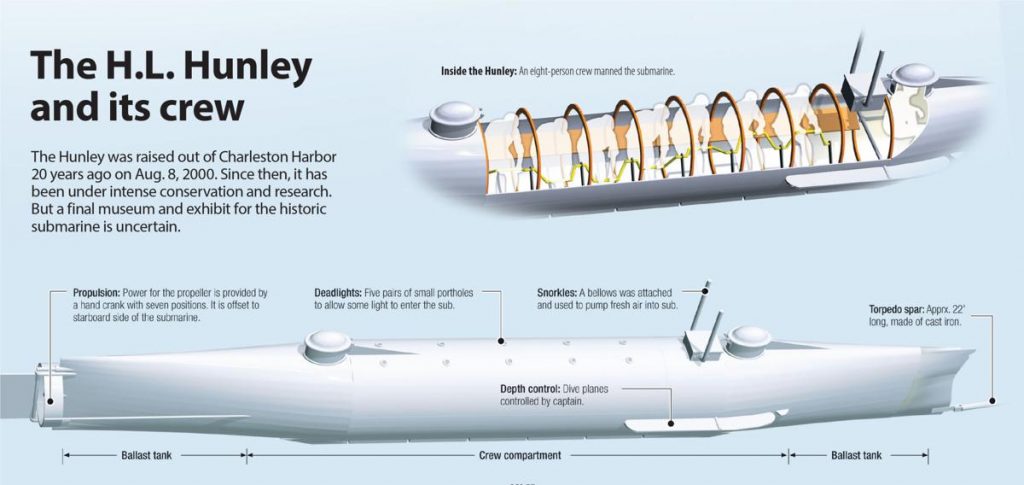

The H.L. Hunley became the first submarine to sink an enemy ship when the hand-cranked vessel rammed the USS Housatonic with an explosive black powder charge and sank the Union blockade ship off Sullivan’s Island the night of Feb. 17, 1864.

The Hunley, with a crew of eight, also sank. The remains of the ship were found in 1995 and five years later, it was pulled from Charleston Harbor.

This led to years of research, conservation and speculation among academics, scientists and historians. But what led to the death of the men is still shrouded in mystery.

In the aftermath of the attack, the Hunley would have been forced underwater by gunfire from the Union. The vessel was sealed shut and there were only two ways to get air, opening the hatch or using snorkels.

In 2019, Clemson researchers found an unused pair of snorkel hoses tucked under a crew bench. Additionally, one the pipes leading to the ballast tanks used to dive and surface the sub was broken. The chaos of the attack may have been too much, and the crew might have been in a hurry to get away, ultimately leading to the men’s demise. It’s also possible the gear wasn’t usable or maybe dismantled just to make room.

In 2004, the eight-man crew was buried in Magnolia Cemetery alongside the other men who lost their lives during testing and development of the submarine. Forensic and genealogical research to discover who they were has been successful, with a majority of the crew now identified.

One of the men, Capt. George E. Dixon, carried valuable golden and diamond jewelry with him. Civil War legend said he was given a $20 gold coin by his sweetheart when he left for war. During the Battle of Shiloh, Dixon was shot and the bullet struck the coin in his pant pocket, absorbing the blast.

A dented coin was found on his hip bone by researchers. The findings and artifacts by experts has been exhaustive. But there is a balance between research and public interest, Wilabanks said.

Researchers think a broken pipe might have sunk the Confederate submarine Hunley. File/Friends of the Hunley/Provided

“The world was interested in the Hunley,” Wilbanks said. “I was glad to see it come up. I’m kind of sorry to see it in its 20th year in conservation.”

Now mostly cleaned, the sub will sit in a conservation bath for about four years to preserve the metal and ready the vessel for permanent public display some day.

For those who first caught a glimpse of it in 2000, they hope that day comes sooner rather than later.