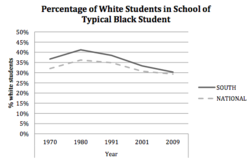

Despite declining residential segregation for black families in the United States, school segregation for black students remains very high — and it is increasing most dramatically in the South, which has led the nation in desegregation thanks to the victories of the civil rights movement.

Those are among the findings of research released last week by the Los Angeles-based Civil Rights Project, which found persistent and serious increases in segregation of public-school students by race and poverty. The changes are most dramatic in the South and the West, where youth of color now constitute a majority of public school students.

“These trends threaten the nation’s success as a multiracial society,” says project co-director Gary Orfield.

The project released three separate studies looking at school segregation in the nation overall and in the South and West specifically. Among the key findings for the South:

* The South is a majority-minority region in terms of school enrollment, second only to the West as the nation’s most diverse, with whites making up 46.9 percent of the South’s students.

* Latino students account for almost the same share of the South’s school enrollment (23.4 percent) as black students (25.9 percent).

* In 1980, just 23 percent of black students in the South attended intensely segregated schools, defined as those with 90 to 100 percent minority students. By 2009-2010, that number had risen to 33.4 percent — close to the national figure of 38.1 percent.

* The share of Latino students attending intensely segregated minority schools has increased steadily over the past four decades, from 33.7 percent in 1968 to 43.1 percent in 2009. Today more than two out of five Latino students in the South attend intensely segregated schools.

* Black students experience the highest levels of exposure to poverty in nearly every Southern state, while in the rest of the United States Latino students experience higher exposure to poverty.

The report also looks at racial segregation in schools in the South’s metro areas. It found that black students in the Raleigh, N.C. area had the highest exposure to white students, though that exposure is on the decline due to the ending of a longstanding socioeconomic diversity policy by the previous school board’s Republican majority. Tampa, Fla. and Memphis, Tenn. have experienced sharp increases in school segregation, while black-white exposure in schools is on the rise in two places where it has historically been lowest: Birmingham, Ala. and New Orleans.

The researchers offer several South-specific recommendations to reverse the troubling trends, including continued or new court oversight of the region’s school districts, the development and enforcement of comprehensive post-unitary plans, and making a strong commitment to pursuing voluntary integration policies.

The Civil Rights Project is also concerned that the issue of school segregation is not getting attention in the current presidential election.

“We are disappointed to have heard nothing in the campaign about this issue from neither President Obama, who is the product of excellent integrated schools and colleges, nor from Governor Romney, whose father gave up his job in the Nixon Cabinet because of his fight for fair housing, which directly impacts school make-up,” Orfield says.

A supporter of the civil rights movement, George Romney was named secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development by President Nixon and proposed an ambitious housing program to promote desegregation. But his plan was met with hostile reactions from local communities and a lack of support from Nixon, who pressured Romney to resign.

By Sue Sturgis, the Institute for Southern Studies