Loyal – unswerving in allegiance[i]

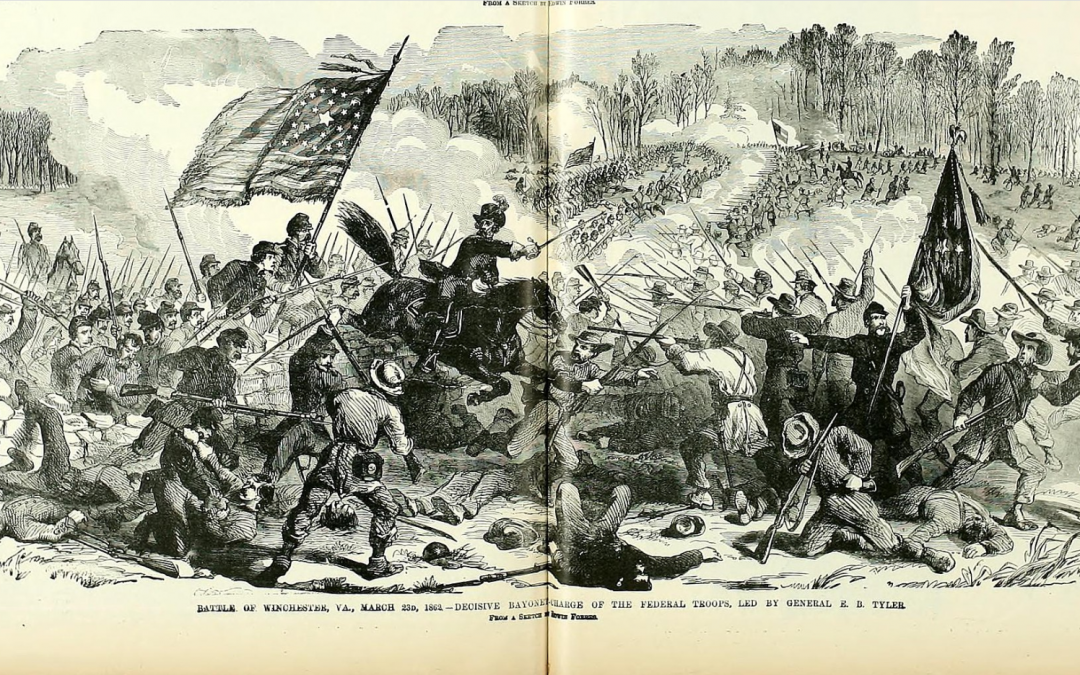

The battle of Kernstown, fought on March 23, 1862, resulted in a Confederate retreat under the cover of darkness and a scored victory for the Union in the Shenandoah Valley. “Stonewall” Jackson’s gamble to regain Winchester had faltered, and he suffered a battlefield defeat. Though the Federals telegraphed proud reports to Washington D.C., the victory sent surprise and alarm. The Union troops slated to shift to McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign or other parts of Virginia could not be spared from the Valley.

One of the things that has long intrigued me about the battle of Kernstown is the concept of loyalty — particularly in the case of Jackson and the Stonewall Brigade. As usual, Jackson commanded without good communication at Kernstown, using two staff officers to carry messages. He tried to respond as the fight unfolded but on several occasions on that March day reacted without complete information, including engaging in battle in the first place. General Richard B. Garnett led the Stonewall Brigade during the battle and had some issues with the unit’s deployment. Eventually the brigade ended up behind an infamous stonewall where they battled and held off Union attacks until out of ammunition. Jackson later charged Garnett and courtmartialed him for six “failings” during the battle, including taking the wrong position and withdrawing the brigade without orders. When Jackson ordered Garnett’s removal from command days after the battle, the Stonewall Brigade and Jackson’s staff officers faced a crisis of loyalty. Would they side with Jackson’s version of the story? Or support Garnett who had been with them during battle? Ultimately, they waver. The real-time primary sources can be divided, but the regimental commanders sided with Garnett. The post-war versions (after both Jackson and Garnett died) tend to be more wavering; many veterans seemed to want to support Jackson but could also see the unreasonable aspects of how he treated Garnett. It becomes a multi-layered story of loyalty, reality, and memory.

On this 160th anniversary of the battle of Kernstown, I wanted to approach the combat history with the lens of loyalty, but look beyond the Jackson/Garnett/Stonewall Brigade incident. What other stories about “unswerving allegiance” to a cause, a personality, or something else could be added to this concept at Kernstown? While studying Gary L. Ecelbarger’s volume on the battle, these six stories particularly caught my attention.

Union General James Shields never set foot on the battlefield on March 23 but would claim the victory at Kernstown was due to his planning and command. In reality, Shields had been severely wounded in a skirmish and lay at headquarters in Winchester, receiving reports of the battle but unable to leave his cot and unwilling to let his surgeon leave. (Nathan Kimble primarily commanded and managed the battle for the Federals.) Despite his unique “command” situation, Shields—an Irish American immigrant—devotedly supported his new homeland. In 1861, he had publicly declared his loyalty to the Union, saying: “There are three things which I am resolved never to do: I will never break my oath of allegiance to this country. I will never betray my trust. I will never fly back upon my adopted country in an hour of peril like this.”[ii]

During fighting around an area of the battlefield known as Sandy Ridge, Company, the 27th Virginia clashed with companies of the 1st West Virginia. Some of these soldiers had been recruited from Wheeling, West Virginia, but some chose to fight for the Union and other for the Confederacy. They had made a choice for their allegiances and now shot at their former neighbors. For at least one family, this moment was “brothers’ war” in all its awful realities. Lieutenant John B. Lacy disagreed with his family’s political beliefs and enlisted for the Confederacy in 1861. His two teenage brothers, Privates David and Columbus Lady, joined the Union unit. It is not known if the brothers were actually on the firing lines at the same time, but they were certainly prepared for action and opposing each other near Kernstown that day. Whether they knew it or not, their loyalties were put to an ultimate test.[iii]

In contrast of loyalty, another pair of brothers fighting in in the 2nd Virginia Regiment refused to leave each other. Both had been wounded and could not keep up as their unit began to retreat in the later evening. George Washington had been badly wounded, the worst injuries of the two; his brother Bushrod C. Washington struggled to carry him off the field. Both young men were captured by Union cavalry, part of the 30% casualty losses sustained by the 2nd Virginia at Kernstown.[iv]

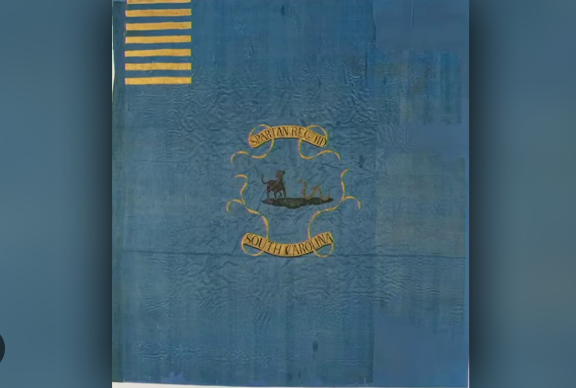

The 2nd Virginia took their loyalty to their regimental standard deadly seriously. At Kernstown, they lost four colorbearers. Ephraim B. Crist, J.B. Davis, Richard H. Lee, a soldier whose name is not known, and James W. Allen all carried the flag and kept it from falling. Lieutenant Lee sprang over the infamous stonewall and defiantly waved the battleflag at the advancing 67th Ohioans. Surprised, the soldiers from Ohio decided to stop firing for a couple of minutes, shouting, “Don’t shoot that man; he is too brave to die.” Then, realizing their ceasefire could have other consequences, they ordered Lee to get back over the wall…and started shooting again. By the end of the battle when the flag left Colonel James Allen’s hands, it bore the marks of 14 bullet holes and the flagstaff had been shot or somehow broken in half.[v]

William G. Murray, Colonel of the 84th Pennsylvania Infantry, had a loyalty and leadership crisis just prior to Kernstown. His regimental officers had actually asked for his resignation on March 21, a result of a mutiny and declaration that he had “yet failed to discover that peculiar genius which qualifies for martial command…. Lives are not to be imperiled wantonly because of inefficiency ascribable to the incompetency of your command.”[vi] Murray refused to resign, leaving it to the State of Pennsylvania and his future conduct in battle to decide his fate. Two days later during the battle of Kernstown, his officers and men followed him into battle, advancing on a Confederate artillery position as directed. Colonel Murray’s horse was shot; his regiment sought shelter lying on the ground, just forty yards from the Confederate guns that pinned them in an exposed position. Murray saw a third of his regiment turn to casualties before his eyes, but he paced his line, keeping the men organized and steady. He told his adjutant “We must either advance or retreat, and we won’t retreat!” Rallying his men, he prepared again to carry out his orders. Murray raised his sword and stood by the regimental flag, shouting above the sound of battle for his men to charge. At that moment, a Confederate bullet struck his forehead. The colonel fell back against his men and his flag, dying on the field. Colonel Murray was the highest ranking Federal officer killed at Kernstown and his regiment also took the most casualties, 36% in forty-five minutes under fire. The questions of Murray’s leadership were put to rest; he had followed his orders at Kernstown, and though the cost had been high, the men stayed loyal on the field and rallied at his command.[vii]

Private G.K. Covert from the 7th Indiana had a tintype of a young woman. In the streets of Winchester, on Sunday morning before the afternoon battle, he showed off this prized possession and claimed the girl was his sweetheart. A comrade snatched the tintype and said the photograph would be his, probably along with other banter or insults of varying humor. Covert took it offense and fist-fought to get his photograph back. His loyalty to the girl in the tintype saved his life later that day. Covert regained his prized photograph and stowed it with his Bible in his left coat pocket. That afternoon Covert charged toward the Confederate’s stonewall, and a bullet slammed into his chest…only to be slowed by the layered pages of his Bible and stopped or diverted by the tintype photograph. For unknown reasons, Covert didn’t marry the girl in the photograph, but his loyalty to her and determination to keep the photograph probably saved his life.[viii]

Unswerving allegiances were questioned and proved at Kernstown. At the command level, regimental level, or individual level, these stories provide a different way to look at the battle experience on March 23, 1862, in the Shenandoah Valley. While the Stonewall Brigade may be at the center of one of the most known “question of loyalty” moments as Jackson removed their commander, there are many other instances of leadership loyalty or personal devotion that resulted in loss or continued military service.

Sources:

Peter Cozzen, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

[i] Merriam Webster “Loyal.” Accessed online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/loyal

[ii]Gary L. Ecelbarger, “We Are In For It!” The First Battle of Kernstown (Shippensburg, White Mane Publishing, 1997) Page 53.

[iii] Ibid., Pages 130-131.

[iv] Ibid., Page 185.

[v] Ibid., Pages 161-162.

[vi] Ibid., Page 79.

[vii] Ibid., Pages 165-166.

[viii] Ibid., Page 136.

–emergingcivilwar.com