SOUTH CAROLINA: The Miniature Man: Richard Lushington, his Jewish Militia, and Charleston High Society

It was no small feat to locate the miniature double portrait and get it to Charleston. And the visage on one side of the medallion-sized object, that of Richard Lushington, recalls an extraordinary slice of Revolutionary War history.

It’s a story that, like many others of the period, had to be pieced together by a sleuth.

Now the portrait is on display at the Charleston Library Society, Lushington’s story is documented, and the story of the story — well, that’s for us to entertain right now.

It begins a few years ago when the South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust secured property near Beaufort: the site of the 1779 Battle of Port Royal Island. Research done during that project brought to light a certain volunteer infantry regiment that participated in the victorious land battle against British forces. The regiment, it turned out, was comprised of men from Charleston, dozens of whom were Jewish merchants with shops on King Street.

This Company of Free Citizens was commanded by Richard Lushington, according to a partial muster roll discovered by the researchers.

Doug Bostick, president and CEO of the S.C. Battleground Preservation Trust, scratched his white beard and wondered: Who was this fellow? Maybe a Jew himself? Maybe a Charlestonian of the particularly courageous sort?

Bostick, who knows a lot, didn’t know. So he and his team started to dig.

“We searched through the archives here in town, sent a staff member to the New York Public Library, searched the National Archives — essentially pulled on every thread we could find,” he said. “Slowly, the real significance of Richard Lushington began to emerge.”

Bostick assigned historian George McDaniel Jr. the task of plucking Lushington and his regiment from the obscure regions of American history and illuminating their particular contributions. It turns out their contributions were significant.

Commander

During the late-Colonial period, militias consisting of city dwellers were formed according to residential district. Lushington’s district ran from Boundary Street (today Calhoun Street) down King Street to Broad Street.

This was a mercantile area, as it is today. Shops lined the street level; families who owned the shops lived above them. A number of Charleston’s early merchants were Jewish immigrants in search of freedom and opportunity across the Atlantic Ocean, where a country was about to be born. They were committed to their new home, eager to participate in society as full-fledged citizens — and that included signing up for war.

McDaniel said about 40 percent of Lushington’s regiment was comprised of these Jewish merchants.

The unit was deployed to confront British troops near Beaufort in January 1779, a battle that bolstered the morale of Patriot forces everywhere. They joined the failed Siege of Savannah that September. And they helped to defend Charleston against the successful British siege of the city in 1780.

After the fall of Charleston, Lushington was one of about three dozen prominent Charlestonians arrested by the British and sent to St. Augustine. Joining him were Christopher Gadsden, Alexander Moultrie, Edward Rutledge and Josiah Smith, who kept a diary of those months of imprisonment.

The American officers weren’t treated badly. They were allowed to rent villas, wander through orange gardens and keep their enslaved servants with them, McDaniel said.

Gadsden, a firebrand, refused to sign his parole papers, effectively admitting he was wrong to fight the British, so he was kept in the fortress stockade for the 10 months or so that elapsed before a prisoner exchange set them all free.

Lushington quickly returned to South Carolina and took command of a garrison at Georgetown, where he finished out the war. Now, finally, he could go home to Charleston and continue where he left off.

Social climber

What was he doing before the Revolution interrupted his efforts? Claiming his place in Charleston society.

Lushington, it turns out, was neither Jew nor landowner. He was a Quaker. A slave-holding Quaker undaunted by the battlefield, willing to produce and sell alcohol, and eager to climb the social ladder.

Weren’t Quakers abolitionists? Weren’t they opposed to violence? Didn’t they reject religious hierarchies and elaborate rituals, abstain from alcohol consumption and strive to uphold high moral standards?

Quakers, who trace their origins to 17th century England, settled in the North American colonies as early as the 1650s. Lushington’s parents had come to Charleston from Kent, England, in time to bring their son into the world in, or very near, 1750.

At that point, the pacifism was merely suggested and objections to slavery nascent, at least in Charleston, McDaniel said.

Lushington grew up to become a prominent merchant who operated a dry goods store, selling all sorts of things. He also ran a rum distillery at his residence, the Still House, located at the corner of Hasell and Bay streets. And he owned 11 enslaved people, which was considered a large amount at the time.

In 1774, he married Charity, the widow of William Ball. The Ball family was among Charleston’s most successful, with multiple rice plantations in the Lowcountry. The fact that this Quaker merchant could marry such a woman is an indication of his successful social climb, McDaniel noted.

In 1780, between wartime engagements, he followed the example of many respected men in town and joined the Charleston Library Society. After the war, he returned to his business, his distillery, his library and his wife. He became a member of the privy council and a warden of the city. At some point, an artist, following a trend of the time, painted miniature portraits of the couple, which were encapsulated back-to-back.

On the first day of summer in 1790, a Friday, he caught the “putrid fever” — typhus. On Monday, he died. And that was the end of Richard Lushington.

He was almost certainly buried in an unmarked grave of the Quaker cemetery, located at the southeast corner of what’s today King and Queen streets, which was just outside the city walls. (The human remains were exhumed and relocated to a plot behind the county courthouse in 1969 to make way for the construction of a parking garage.)

“For a series of years he was honored with the confidence of his fellow citizens, and in the various public stations to which he was called by their suffrage, he acted with the strictest integrity,” stated an obituary printed in the City Gazette on June 23, 1790. “The many important and meritorious services he has rendered to his country must ever claim its gratitude, and a respectful veneration for his memory.”

Apparently, the author of the obituary thought of Lushington not only as a war hero but as a good man.

“His manners were plain and unaffected, his disposition the most benevolent and humane; and to the many virtues of an excellent citizen he united those of an affectionate husband, a generous and uniform friend, and a kind and indulgent master.”

He had largely achieved his goals, McDaniel said.

“Who knows where he would have gone had this disease not struck him down so quickly,” he said.

Thanks to McDaniel’s sleuthing, we know where Lushington’s miniature portrait ended up, though.

Recovery!

As he was digging through the documentation, gleaning bits of information about the Quaker merchant, McDaniel came across black-and-white photographs of the portraits, snapped in 1936 for a show at the Gibbes Museum titled “Exhibition of Miniatures Owned in South Carolina and Miniatures of South Carolinians Owned Elsewhere Painted Before the Year 1860.”

Beneath the images was a key phrase: “Lent by Mrs. Oemler of Savannah.”

Clues!

Sure enough, McDaniel soon came across a 2007 obituary for a Savannah woman whose surname was Oemler. It mentioned a son who, it turns out, was in Beaufort. The man told McDaniel of a Wilmington Island connection.

McDaniel did what good historians do: Put Google to use. He entered “Wilmington Island, Ga.” And found a Facebook group called “History of Wilmington Island.” Naturally, he joined the group. Then he wrote a long post sharing his identity and mission, and he attached the photos of the portraits.

Twenty minutes later, a response from Elizabeth Adams.

“I have them. I just sent you an email.”

Adams had inherited them from her mother, Constantia Oemler Smith. The portraits were kept in a little china cabinet with other family treasures. Adams had no idea who the two figures were, but she had a hunch the double-sided miniatures were old, and maybe valuable.

Around a decade ago, the PBS TV series “Antiques Roadshow” came to Savannah. A family friend who deals in antiques urged Adams to go get the little paintings appraised. Someone on the show’s staff knew the object dated to the Revolutionary War period but couldn’t identify the faces.

In the summer of 2022, Adams read McDaniel’s Facebook post, noticed the name Oemler, then scrolled down to the bottom and saw the photos.

“I’m an Oemler,” she wrote to McDaniel in the email.

The two got to talking, and Adams was impressed with the historian’s knowledge and enthusiasm, she said. She learned about Lushington’s exploits, his connection to the Library Society, his unquakerlike Quaker ways.

It didn’t take long for her to reach a conclusion: The miniatures needed to go home to Charleston.

Back in Charleston

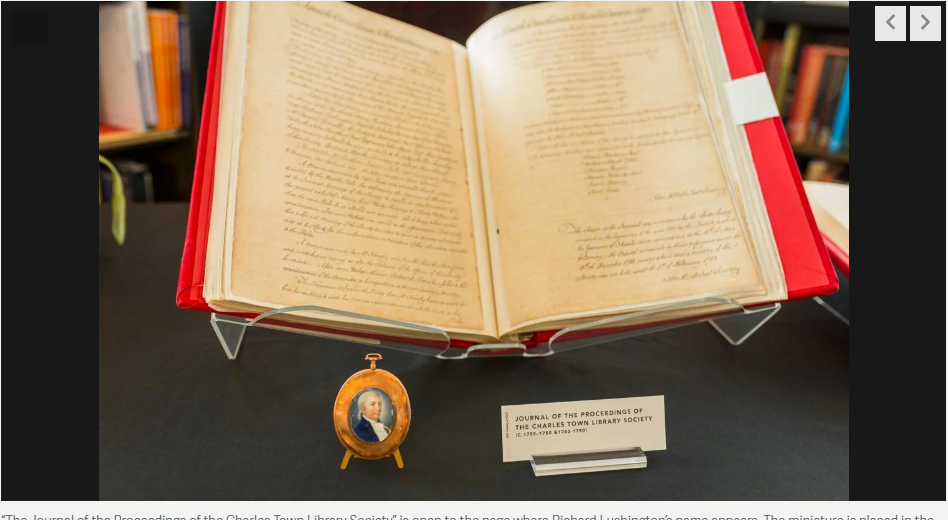

Lushington’s name appears in the Library Society’s “Journal of the Proceedings” and in the “Book of Committee Minutes.”

He was a member during a difficult phase, Special Collections Librarian Lisa Hayes said. He joined in 1780, just two years after a devastating fire destroyed hundreds of structures in the old city, including the Library Society’s leased warehouse in Kinloch Court (today Philadelphia Alley).

“The Charles Town Library Society’s valuable collection of books, instruments and apparatus for astronomical and philosophical observations and experiments, etc., etc., is almost entirely lost,” the South Carolina and American General Gazette noted at the time.

So Lushington’s tenure came during a period of rebuilding, which proceeded haltingly because of the war for independence. Membership was at a low point, just 50 or so people propping up what remained of the organization, Hayes said.

Lushington served on the book committee and was almost certainly concerned with growing the collection. By 1790, the year of his death, only about 150 books had been purchased, bringing the number of volumes in the collection to 342 — about 7 percent of its size before the fire.

Today, the Library Society — the oldest cultural institution in the South and the second-oldest library in the country with continuous circulation — is located in a lovely Beaux Arts building on Lower King Street and boasts a collection of 110,000 volumes. It also has four exhibit cases in the corners of the main room devoted to the history of the institution. The first, which contains 18th-century objects, now includes the miniature portraits, which Adams decided to donate.

The visages of Lushington and his wife, Charity, are positioned by the opened “Journal of the Proceedings,” which includes the Quaker merchant’s name.

“(The miniature) just fits so nicely knowing that he was a member here,” Hayes said. “And it fits so nicely in that particular case. It all came together really well for us.”

Adams said she was glad to reunite the portraits with the city of their origin.

“It makes a lot more sense for (Lushington) and his wife, Charity, to be on display at the Library Society, and for people to know about his history, than for him to be sitting in the china cabinet in my house,” she said.

Bostick, accustomed to history of the messier kind, was thrilled to see this chapter fleshed out and reach a happy ending.

“To have the miniature donated to the Library Society was a seminal moment,” he said. “Richard Lushington came home.”

Epilogue

After her husband’s death at 39 years old, Charity found a new man, according to McDaniel’s research. In 1794, she married George Forrest. Two years later, Forrest paid a visit to the bank, cleared out the accounts and disappeared. Call it Charity’s charity.

She was left alone and bereft. Her brother-in-law, Daniel Latham, a Quaker famous for carrying the news of the 1775 Patriot victory at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, provided help.

As the new nation forged ahead, it grappled with the issue of slavery. Quakers joined the abolitionist cause, rejected religious dogma and disavowed warfare. The miniature portraits of Richard and Charity Lushington were passed along through the generations until they ended up in a china cabinet near Savannah.

The commander of a largely Jewish militia, dead at 39, soon was a faint memory, then mostly forgotten. He became but a faceless footnote of the American Revolution.

Now, his face is there for all to behold.

Today, Lushington’s legacy is restored.

–postandcourier.com