SPARTANBURG — When conversations about perseverance during the oppressive Jim Crow Era arise, the topic of stage magic isn’t the first to come to mind.

Despite laws that were in place at the time, many Black entertainers who came from the South traveled across the U.S. to make a living using their talents.

In the case of the Armstrong family of Spartanburg, it was magic.

Now, a Greenville-based filmmaker and genealogical researcher is creating a documentary to tell their story.

The feature, “Going Fine Since 1889: The Magical Armstrongs,” will highlight the family’s contribution to magic history and African American culture during the oppression of the era from the 1870s to 1960s.

“They were really a dynasty, and it’s very unique to have a dynasty of African American performers like that during that era,” filmmaker and researcher Jennifer Stoy said of the family that lived on the Northside of Spartanburg on College Street for more than 50 years.

The Armstrongs’ story is that of a quiet rebellion, Stoy said, and one that isn’t well-known. She came across the family by accident while doing research for another project. Stoy said while gathering information for the documentary, she asked elders in Spartanburg if they’d heard of the Armstrong family, and many did not know of their story.

“It’s really kind of a lost piece of history for Spartanburg that I think needs some telling,” she said.

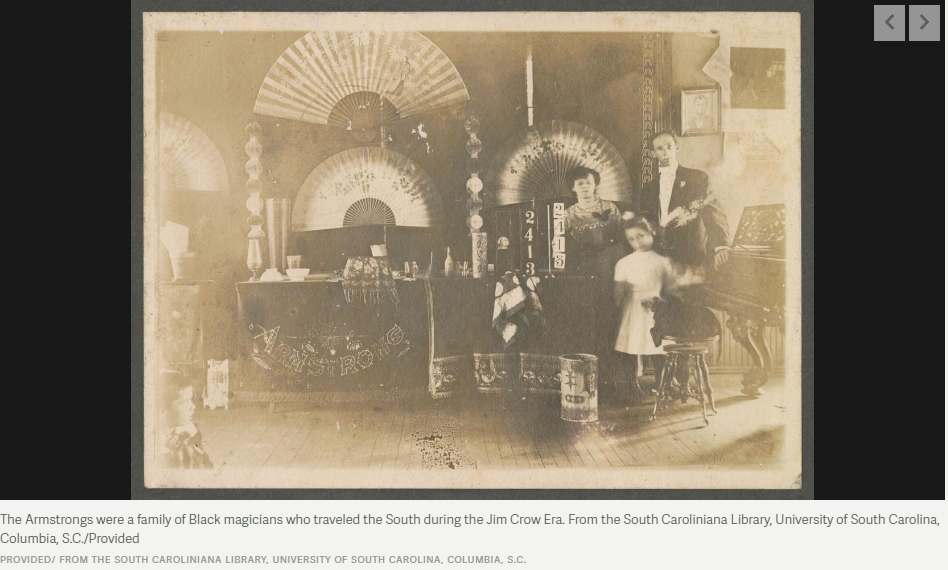

Illusionist John Hartford Armstrong, his wife Lillie Belle Armstrong and daughter Ellen Emma Armstrong performed as “The Celebrated Armstrongs.”

Some details of John’s early life are unknown, but he was born in 1874 and spent many years living in Spartanburg.

In the late 1800s, John and his brother performed together until the their act split for unknown reasons, and John went on to perform with his wife and daughter.

John was previously married to Ida Belle White in 1903, and together they had daughter Ellen. Ida died in 1907 and a year later, John married Lillie Belle, who was a schoolteacher from Spartanburg. John trained Lillie Belle in a two-person magic code act, where she joined his show as a mentalist.

At the age of 6, Ellen began performing with her father and stepmother.

Ellen specialized in a mentalist act. She’d incorporate chalk art animation into the show through chalk talks, where she’d draw while telling a story, and her picture would rapidly change into something else.

After her father’s death in 1939 and her stepmother’s death in 1947, Ellen continued to perform. She was the first Black woman magician to have her own solo act and became known as a “cartoonist extraordinary.”

She went on to perform until the mid 1950s, married later in life and moved to Columbia. She died in 1994.

For Dwain Pruitt, chief equity officer for Wofford College and a historian, the Armstrong family stands out for the longevity of their careers. He said magic is a difficult craft that takes lots of practice and dedication.

Pruitt described the family as having a great deal of imagination and mechanical ability because they built their own sets and performed their own tricks.

“They were exceptional people who had lots of skills, had access to capital and were really, by all accounts, exceptional entertainers,” Pruitt said.

Pruitt said the average Black person living in South Carolina during the 1920s would have been a laborer working on farms or in the city providing domestic labor for low wages, but Spartanburg did have communities of middle- class and wealthy Black families.

“When you read about the expense of their props and what money they were investing, they clearly were putting a great deal of money into their show,” he said. “They probably would have been, based on how much money they had invested in the show, among the wealthier people in the city.”

The Armstrong family primarily performed at Black theaters, churches, schools and universities, as well as venues a part of the Chitlin’ Circuit, a network of dance halls, juke joints, nightclubs and theaters across the U.S. where Black performers could safely put on shows between the 1930s and 1960s.

The documentary is important, Pruitt said, because it shows that there are multiple narratives in African American history.

The documentary, its rough cut expected by the end of this year, will include interviews with historians, magicians, magic collectors and scholars. There will be some animated sequences, historical and archival footage and re-created tricks and illusions that the family performed.

“I think it’s going to be special for the magic community, for Spartanburg and Southern filmmaking in general,” Stoy said.

Throughout the documentary, magician Randy Shine will demonstrate the tricks performed by the Armstrongs in a modern silent movie-type film style.

Stoy was able to connect with historian and magic collector Michael Claxton, whose collection includes original Armstrong props and family scrapbooks. She plans to use photos of Claxton’s collection and incorporate information from the scrapbooks into the documentary.

The family took a lot of publicity photos, and the scrapbooks have testimonial letters and newspaper clippings that helped Stoy put together a timeline of where the family traveled over the years.

One of the family’s scrapbooks from the South Caroliniana Library will be used to help with storytelling.

Once the documentary is complete, Stoy would like to have community screenings across South Carolina. She said the first screening would be in Spartanburg, and then she’d like to host more screenings at places that are still open where the Armstrong family performed.

The hope is to have it aired on the Public Broadcasting Service network.

Producers are still seeking additional funding for the documentary, but some support for the project has come from South Carolina Humanities, The Society of American Magicians and private investors.

Ultimately, the project will involve getting the city of Spartanburg’s permission to construct a monument where the Armstrongs’ house stood on College Street.

–postandcourier.com