FLORENCE COUNTY — On the walls of the South Carolina Statehouse hangs a moment marking the end of the Revolutionary War — and the conclusion of a bloodstained episode in the state’s history.

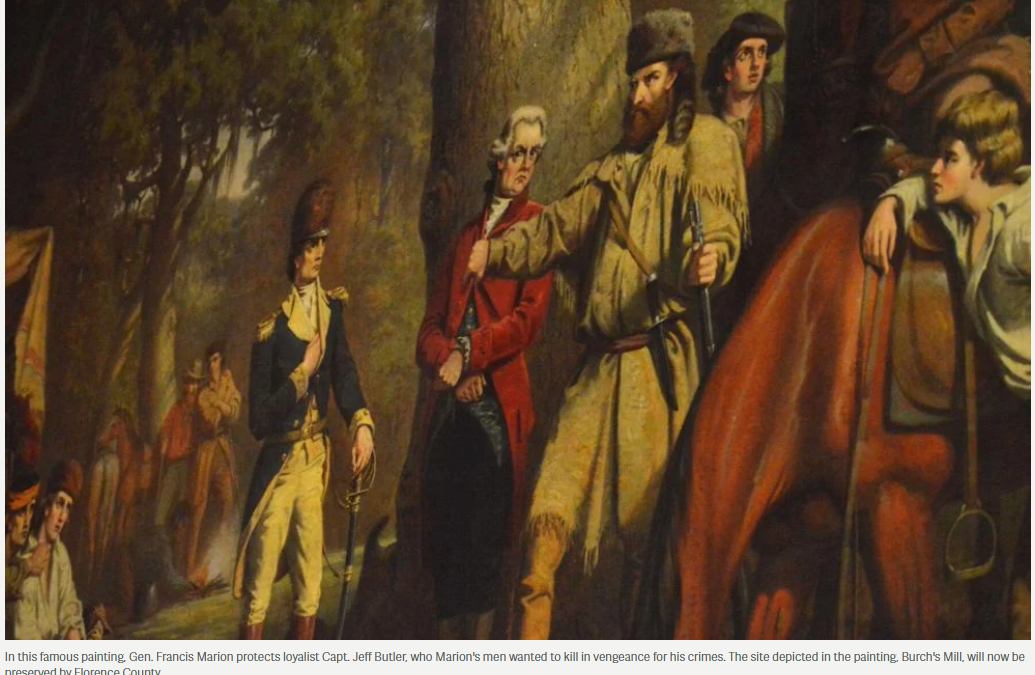

The painting depicts a real-life event in which Gen. Francis Marion granted mercy to British soldiers he’d fought tooth and nail to defeat. It’s a moment that helped grow Marion’s myth and symbolizes the reunification of a state torn apart by the Revolution.

243 years later, the location depicted in the painting, known as Burch’s Mill, will be preserved for the public after Florence County purchased the historic site.

“It creates a great opportunity to tell the whole story of Florence County,” said Ben Zeigler about Burch’s Mill. Zeigler is a local attorney, chair of the Archaeological Institute for the Pee Dee and longtime advocate for the preservation of the area.

Florence County Council members unanimously agreed to spend $3.5 million to preserve the roughly 375-acre property on the Pee Dee River. County Administrator Kevin Yokim said plans are in their earliest stages, but the county is exploring how to use the site for archeology, historic education or other recreational uses.

Burch’s Mill not only played a role in the Revolutionary War, it’s also the site of an important geological formation, an example of early life in colonial South Carolina and one of the few stretches of publicly-owned land along the Pee Dee River in Florence County.

Aside from Snow’s Island, it’s one of the county’s most historic sites, Zeigler said.

“There’s all kinds of cool stuff there that needs to be protected,” he said.

Burch’s Mill’s most famous episode occurred at the end of the Revolutionary War.

The war tore apart backcountry communities in South Carolina, according to Zeigler.

American and British forces clashed in battles that sometimes saw neighbors face to face in combat. When they weren’t fighting, the two sides pillaged the countryside, collecting supplies, exacting revenge on fellow South Carolinians and keeping the backcountry on edge.

On one side was Marion, who crisscrossed the Pee Dee harassing British troops. On the other was Maj. Micajah Ganey, the leader of a loyalist militia and one of the men charged with putting a stop to Marion’s activities.

Burch’s Mill was a strategic point during the war, and both British and American troops camped at the site, Zeigler said.

The mill’s significance didn’t begin then, though.

The mill is the site of a unique geological formation that contains numerous marine fossils — shark teeth and fish fossils and belemnites, a type of cretaceous squid. It’s the site of Native American activity dating back thousands of years. And it’s one of the first sites settled by Europeans in the early 1700s.

By the time of the Revolution, colonists had built a ferry, a store and a grist mill in the area, among other structures, Zeigler said. Joseph Burch purchased the land in the mid-1700s.

It’s the role Burch’s Mill played at the end of the Revolution that makes the site particularly significant, though.

In the spring of 1782, as the war came to a close, Marion and Ganey agreed to meet at Burch’s Mill. They planned to negotiate an end to the years of violence, according to a historic marker that once stood at the site.

On June 8, after extensive negotiations, Marion and Ganey signed a final treaty. In return for their freedom, the loyalists agreed to lay down their arms, return civilian property and serve in the patriot militia for six months.

As loyalists arrived to surrender, Marion remained at Burch’s Mill, Zeigler said.

One day, one of the most infamous loyalists arrived at Marion’s camp: Captain Jeff Butler.

Butler was responsible for the Lynches Creek Massacre, according to William Dobein James’ 1821 biography of Marion.

During the massacre, Butler surprised a patrol of Marion’s men and trapped them in a home near modern-day Johnsonville. Butler set the house aflame to drive out the patriots. Promised they would be treated mercifully, the men surrendered. As soon as they laid down their arms, Butler ordered them killed, according to James.

When Butler arrived in Marion’s camp, Marion’s men wanted to treat him with the same level of mercy he had given them, according to a 1959 biography of Marion by Robert Bass.

Marion refused.

“Both law and honor sanction my resolution to protect him with my life,” Marion reportedly told his men. Even as other patriots threatened to drag Butler from Marion’s tent, Marion stood resolute.

That’s the scene now depicted in a painting outside of the South Carolina Senate.

The painting, by William Washington, shows the militia standing beneath a broad tree. They are dressed in ragged, mismatched clothing, each staring angrily at Butler. Butler stands with his hands tied. Marion stands next to the loyalist, protecting him.

“It’s become one of those scenes … that is painted in the 19th century to help expand and expound upon the myth of Francis Marion as the quintessential American soldier, (the) people’s soldier, but also a man of decency and dignity and honor,” Zeigler said.

Zeigler’s father, state Sen. Eugene “Nick” Zeigler, campaigned for the state to purchase and hang the painting in the Capitol.

After the war, activity at Burch’s Mill declined. Today, there’s nothing left above the surface.

But below the surface there’s likely telltale signs of colonial life and the trials of the Revolutionary War, Zeigler said.

He hopes the site will be preserved and explored by historians and archaeologists to reconstruct what life was like and educate the public on the story of Florence County.

“(There’s) a lot of great things to tease out of the story of Burch’s Mill, but it’s going to be a wonderful addition to the resources that the county offers,” Zeigler said.

–postandcourier.com