Roughly 2,300 steps link the circuitous walk from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian to the stately entrance of the United States Capitol. This walkway along the National Mall is a historic part of Washington, D.C., heavily trafficked by sightseers stopping to admire and photograph some of the city’s most iconic structures.

On Friday, some 1,500 Native veterans will travel that route in a distinguished processional of former service members from every branch of the military to celebrate the newly installed National Native American Veterans Memorial. Descended from tribal communities and cultures that predate any building or structure in the area by hundreds of years, they will be the icons.

Native Americans’ service to the U.S. is a most enduring and complicated sacrifice of self, framed in a promise to uphold a government that has historically targeted, swindled and decimated their communities several times over. And still, Indigenous people have served valiantly in every major conflict, every capacity, every generation since a formalized military was raised in 1775 for what became the Revolutionary War.

The celebration around the National Native American Veterans Memorial—the first national landmark in the nation’s capital to commemorate the military contributions of American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians—doesn’t dodge the truth of that problematic history. Those 2,300 steps will be part of a journey Native veterans have taken communally, connected as a people with equal parts pride in their heritage and pride in the fortifying service that has bolstered the U.S. military.

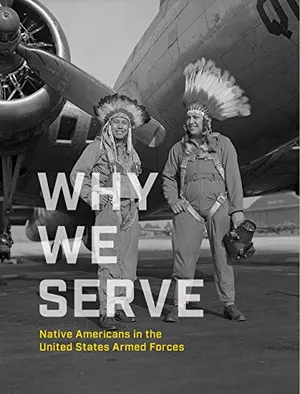

Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces

Why We Serve brings fascinating history to life with historical photographs, sketches, paintings, and maps. Incredible contributions from important voices in the field offer a complex examination of the history of Native American service.

The military mindset burden

“It’s not necessarily that we believed in Vietnam or any of the wars. It was a time that our people came forth to earn their rights—that’s right up there with respect,” explains Boye Ladd, a former Army Ranger from the Ho-Chunk and Zuni Pueblo tribes who served in more than 30 combat missions during Vietnam. Wounded in battle in 1971, he has since traveled the country as a member of the prestigious Red Feather Society, giving keynote speeches, dancing in powwows and leading Indianizing workshops, educating participants about the traditions, etiquette and beliefs of Native people.

At the end of a presentation, he says, someone will often approach him in tears, overwhelmed with fresh empathy or understanding for a father or uncle or brother who hadn’t returned from the military the same as he went in, broken by the trauma of killing other humans. The burden of maintaining a wartime mindset gets heavy, says Ladd, who connects Native Americans back to their traditional faith practices as a healing source.

“According to the original teachings of our people, there’s a relationship between the warrior and the enemy and the creator. When you take the enemy, it becomes a part of your life for the rest of your life. It becomes like a monkey on your back. You have to take care of them. You have to feed them throughout your lifetime. Through ceremonies, through our faith, through our religion, through powwow, we honor that belief of always feeding the enemy, taking care of the enemy or giving in their honor. You know, you try to help other people through the experience,” he says of the sometimes emotional responses he encounters, “because that’s a relationship that’s gone on for centuries among our people.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a8/29/a829428a-91b8-4bb5-8b9f-b506d8b12d32/gettyimages-161106951.jpg)

Artist Harvey Pratt, a Marine Corps veteran and member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma, infused that dynamic into the design for the National Native American Veterans Memorial, respecting the distinctions that exist among the approximately 574 federally recognized American Indian tribes but incorporating the commonalities that culturally thread them together.

Pratt’s concept was chosen from 120 submissions, and the resulting structure, completed in 2020 and nestled in a scenic living landscape complete with an urban wetland, incorporates an interactive gathering space with water for ceremonies, benches that invite visitors to be still and reflect, and four lances where veterans, their families, tribal leaders and community members can tie prayer cloths used by many Native people as a symbol of spirituality.

To wholly appreciate the sacrifices and contributions of Native veterans is to dismantle the antiquated stereotypes that have followed them into service since the Revolutionary War. Native soldiers are not especially adept at navigating jungles or brush, nor is every Native American a natural-born warrior.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/d7/0cd79d47-7de7-4cf7-843f-812300028a23/nnavm_2020ak23_223_a.jpg)

Myth of the warrior tradition

In fact, not all Native American cultures even have a military tradition, according to Alexandra Harris, senior editor at the National Museum of the American Indian and co-author of Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces.Some, like the Hopi in northeastern Arizona, have historically taken up arms only if attacked. Contrary to the unilateral portrayal and perception of American Indians that has been pervasive in movies and media, there is a vast diversity of Indigenous traditions surrounding war, Harris explains.

“The darker side of a ‘warrior tradition’ is that non-Native people have assumed that Indigenous service members have a sort of innate, supernatural ability in warfare, particularly for scouting. This means that Native people have been placed in positions of greater danger and have suffered higher mortality rates than other ethnicities in some cases,” she says. The adage that Native Americans serve in the military more than any other racial or ethnic group is complicated, she says, and adjusted for data, not necessarily true, but institutions including the United Service Organization report that since 2001, 19 percent of Native Americans have committed to the armed forces, compared to 14 percent of all other ethnicities.

The numbers suggest a higher rate of service among American Indians, but enlisters are driven by the same impetuses as people of other groups—to see the world, to get out of poverty or a bad situation, to get an education. Yet there is a purely Indigenous influence that goes back to the cultural commitment to serve others, Harris adds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a9/ad/a9adcd33-da19-4aa8-b3ac-2aee66da580c/mitchelenebigman.jpeg)

“Often there is great family and community influence to join the military, but not always. Sometimes we are all inclined to explain Native American service in the military simply, when the reality is more complex and may ask more questions than history’s evidence answers. The fact that Native people have served a government that historically misused and mistreated them may be the most confusing aspect of this history,” she continues, “but when you look at it from the perspective of Native peoples’ commitment to serving their peoples, communities and homelands, it becomes clearer. For most of the veterans I interviewed, they hadn’t considered their service to be part of their Native identity. But their service often was a reflection of cultural values, which differed between Native Hawaiian, Alaska Native and American Indian cultures. A common thread was protection of homelands and community.”

The bravery to make corrections

That protection has required the bravery to demand the correction of injustices and defend the sanctity of Native culture as much as it has to enlist and engage in conflict.

In a room full of men, some categorically outranking her on the personnel hierarchy, Mitchelene BigMan has not shrunk or made herself invisible to avoid calling out wrongdoing, even in the homogeneity of the military.

Once, after her troop had been practicing battalion formations under the crisp instruction of a commanding officer and the cadets were preparing to be dismissed, he announced his final directives before the room erupted into a swirl of movement and inattention. “I want to see all the NCOs,” she remembers him saying, “because we’re gonna have a powwow.”

It was a verbal gut punch to BigMan—a proud member of Crow Nation—and from the back of the room, she raised an immediate and unapologetic protest. “I yelled ‘as you were, Sergeant Major,’” a command usually leveled from superior to subordinate, not the other way around, and certainly not in front of a roomful of witnesses and, at the time, even more certainly not by a woman to a man in charge. “Everybody heard me and turned around like, ‘I can’t believe you said that,’” BigMan remembers.

“But he was wrong. I said, ‘I’m going to tell you something. I’m going to school all of you NCOs right here. This is what a ‘powwow’ means: It’s a spiritual gathering. It’s where you meet friends. It’s part of us. So when you use that it in that context, you’re wrong. It’s called a ‘disparaging term.’ And I find it offensive as a Native American.”The moment did not turn on her—the officer apologized to BigMan and advised her fellow cadets in the room to be mindful of colloquializing a term that is sacred to another.

Activism would go on to define BigMan’s 22-year military career. She first joined the Army when she was 21 to escape the stunning rates of domestic abuse and chronic unemployment on the Montana Crow Reservation she grew up on. Her work as a track mechanic often made her the only woman in her battalion—“a challenge in itself,” she says—but her advocacy for women as a survivor of sexual abuse both outside of the military and in it compelled her to do something specifically for women in her community.

In 2010, she founded Native American Women Warriors, the first recognized color guard comprising solely Native American women. The group has traveled extensively, performing at inaugurations for Presidents Joe Biden and Barack Obama, and in a full-circle moment, the ceremonial dress she wore for the latter is part of the collections at the National Museum of the American Indian. The color guard will also lead this week’s processional on the Mall. For BigMan, representation is an important part of preservation—of the Native culture and of the Native people themselves.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4d/b1/4db123fd-fd2d-4eb1-b2f7-c885dbcb7946/bigman.jpg)

“I used to tell people, ‘Don’t get caught up in the Hollywood Indian, because Natives come from various lifestyles. You got Southern, you got Northern, you got East Coast, you got West Coast, and every tribe is different. We don’t all have the same language. Not everybody lives in a teepee.’ I think the hardest thing was the disparaging terms and disparate treatment that we received as Native Americans,” she remembered of her military trajectory. “Because for some reason, society’s got the thought that we have everything. I’m like, no we don’t. A lot of these tribes are below poverty level. Some of us are struggling. Why do you think we join the military to make a better life for ourselves?”

Mainstream American culture tends to focus on a select few heroes in any group not composed mostly of white men. In women’s suffrage, it’s Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In abolitionist history, it’s Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass. In the history of American Indians who’ve served the country in the military, those outside of that immediate community tend to only think of the Navajo Code Talkers, the roughly 400 soldiers who become prominent in World War II for remixing their Indigenous language into a hard-to-crack code. There are so many other names and heroic acts to celebrate.

The ceremony on November 11, Veterans Day, signals the start of a weekend-long tribute to Native service. The hundreds of veterans who will line the sidewalks from the museum’s home on Fourth Street and Independence Avenue to the Capitol will both represent those who came before them and quite possibly inspire Native American service members of the future.

The Native Veterans Procession begins Saturday, November 11 at 2 p.m. at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. The dedication ceremony of the National Native American Veterans Memorial takes place at 4 p.m. The exhibition “Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces” is on the museum’s second floor.

smithsonianmag.com