Across the U.S., monuments to the Confederacy that were decommissioned in the wake of racial violence sit in storage.

Los Angeles-based curator Hamza Walker is traveling the country, both in person and virtually, asking to borrow these monuments for an upcoming art exhibit. In doing so, he is resurfacing old debates in city halls, county headquarters, museum boardrooms and even living rooms.

There are several questions at hand.

How do those in charge of these monuments, whether they are government officials, historic preservationists or families, decide what to do with objects that force Americans to confront a painful part of history that many would prefer to leave in the past?

Does displaying these monuments for public view in museums instead of public parks change them from tools of intimidation to educational opportunities?

Are there aspects of these figures’ legacies that are worth honoring despite their ties with slavery and oppression?

“If history is everything that ever happened, what we do with that is we’re selective,” said Jalane Schmidt, an associate professor at the University of Virginia specializing in the African diaspora. “We select certain moments of history that are worthy of reflecting on, and that’s what these monuments are.”

Walker and his co-curator and project manager Hannah Burstein are not trying to provoke a single answer to those questions, Walker said. They do believe, however, this a conversation that needs to be had.

Tentatively called “Monuments,” the exhibit has been in the works since 2018, Walker said. It gathered new momentum after the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer.

Debuting in the fall of 2023 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, the show will display decommissioned Civil War and antebellum monuments alongside newly commissioned art. Some existing works of art will be incorporated into the exhibit, and it may travel to other museums, as well. So far, he has made requests for nearly a dozen monuments, from New Orleans to Baltimore to Charleston.

“How do you diffuse people’s assumptions of the nature of the contention around these objects and get to a point where they are actually looking and listening rather than taking sides?” he said. “In some cases what you think and what you know will be affirmed, and in other cases it will be radically contradicted.”

Walker recently made a request to borrow Charleston’s statue of John C. Calhoun.

A congressman and vice president, Calhoun died years before Southern states launched the Confederacy, but he is also remembered as a fierce defender of slavery and, to some, represents the city’s dark past. Some push back on the idea that Calhoun’s legacy should be strictly tied to slavery, while others said it is the part of his legacy that has the most impact on the present day.

In June 2020, Charleston leaders voted to take the statue down. For weeks before the announcement, the city saw protests almost daily prompted by Floyd’s death.

City officials are deliberating whether to contribute the statue to the exhibit.

After lengthy discussion, Charleston’s Commission on History voted to recommend City Council approve lending the statue out.

A lawsuit backed by conservative advocacy group the American Heritage Association, however, seeks to keep that from happening. The plaintiffs, descendants of Calhoun and the Ladies Calhoun Monument Association, which erected the statue over 125 years ago, argue the statue was never intended to leave South Carolina.

City Council has not yet voted on the matter.

Debates about the proposal are unfolding across the country and stirring up local sentiments about some of history’s most polarizing figures.

Local decision, national scope

Wade Juandiego, vice mayor of Charlottesville, Va., is aware of the consequences of these debates.

Recently elected to City Council, Juandiego previously served as the superintendent of Charlottesville public schools.

Before classes went virtual due to the COVID-19 pandemic or afterschool activities were canceled, the school district was dealing with the aftermath of another crisis.

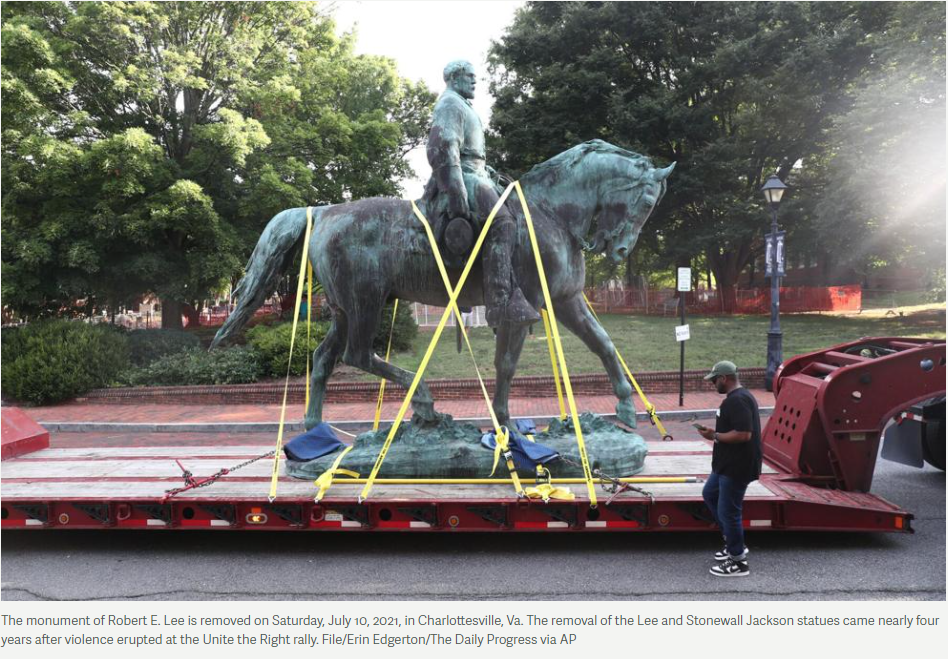

Students were suffering from the aftershocks of the Unite the Right Rally held in Charlottesville in 2017. The rally, which was prompted by the city’s proposal to remove its Robert E. Lee statue, attracted a far-right protest that included white supremacists. Counterprotester Heather Heyer was killed when a man drove through the crowd.

“Many of our students are traumatized by it,” Juandiego said. “We are only 10 square miles. It inundated the entire city. … Many people believed the marches were on their way to a diverse community nearby, and that’s when the young man drove through the crowd.”