There are plenty of things that can trip up a development project in the District, but the Civil War probably isn’t the first one that comes to mind for most people.

But that’s what happened with the Emory United Methodist Church more than a decade ago, when the congregation’s leaders first floated the idea of rebuilding the aging house of worship along Georgia Avenue in the Brightwood neighborhood and adding on a multipurpose building that would be known as The Beacon Center.

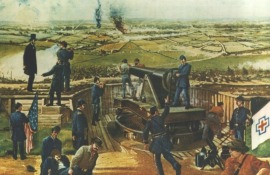

Fort Stevens is the only Civil War battlefield in the nation’s capital. Seen towards the back of this image is Emory Methodist Church, which is moving ahead with plans for The Beacon Center, a five-story building that will surround the church and offer community space and affordable housing.

The rear of the church faces Fort Stevens, the only Civil War battlefield in the nation’s capital. That fact prompted a fierce, years-long fight over the project that only ended last week, when church and city officials joined together to break ground on the $42.5 million, 175,000-square-foot facility that will include 99 units of affordable housing.

During the years that the fight went on, Civil War buffs argued that the planned five-story building would tower over the fort, diminishing the site’s historical significance. But church officials and their partners said they only wanted to use their land to further their mission. As the fight dragged on, they feared that the Ward 4 project — and the affordable housing it will bring — would never get off of the ground.

“There was absolutely some fear that there would be so much control by external factors over a site that’s controlled by the church,” says Jacqueline Alexander, the development director at The Community Builders, a nonprofit developer partnering with Emory on The Beacon Center.

A little history is in order

Here’s the (somewhat) quick rundown: Emory Methodist was founded in 1832, and built its church along what is now Georgia Avenue in 1855. In 1861, the church was demolished by the government to make way for Fort Massachusetts — later renamed Fort Stevens — one of the 68 forts built to protect the nation’s capital during the Civil War.

The fort was the site of a daylong battle between Confederate and Union troops on July 11-12, 1864. It wasn’t a particularly dramatic or bloody battle, spare one fact: President Abraham Lincoln came under enemy fire during the fighting. After the war ended and Fort Stevens was decommissioned, the portion that had once belonged to Emory was returned. By 1922, a new church was being built.

By the late 1960s, the demographics of the congregation had flipped: What was once an all-white church became almost all black, much like the neighborhood around it.

In the mid-2000s, the Rev. Joseph W. Daniels, Jr. laid out his vision for not only a new church for Emory, but also a building that would surround it and serve as community space and residences. In 2009, the church started on the winding regulatory path for the project, which included getting approval from the D.C. Board of Zoning Adjustment.

By 2010, the church had its approvals in hand, but rumbles of discontent were gaining in volume. The National Park Service had opposed the project, largely because the new building would block the view from Fort Stevens to Georgia Avenue, where Confederate troops had marched against the Union encampment.

Opposition from Civil War groups

The Beacon Center also drew fire from the Civil War Preservation Trust, which added Fort Stevens to its list of the nation’s most endangered battlefields. The new building, it opined, “would tower over the fort, significantly degrading the visitor experience.” That same year, the issue was given a national platform by New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, who had grown up near Fort Stevens.

A number of delays hit the project, and it wasn’t until late 2014 that things seemed to be moving forward, so much so that the congregation decamped from the church in preparation for the construction to come. In early 2015, the church applied for a raze permit, which would allow it to demolish everything but the house of worship’s facade.

In response, the D.C. Preservation League applied to have the church designated a historic site, a designation that offers buildings and structures additional protections from being altered. The league, backed by a number of Civil War groups, argued that the structure was historically significant, and razing the majority of it would do irreversible damage to the site.

The historic designation — which the D.C. government granted in May — caught church officials by surprise, delaying construction, threatening their financing and sending them back to the drawing board.

“It did add some additional costs and it did delay because we essentially had to redesign the project,” Alexander says. Redesigning the project cost an additional $4 million, say church officials, and delayed the project by two years. It also threatened the project’s financing, leaving many church officials worried about whether The Beacon Center would ever come to be.

It also prompted feelings of anger that a Civil War battlefield that for years had been ignored eventually could derail a project the church wanted.

“You’re always going to have folks who are really committed to preserving Civil War history and just want things to stay the way they are. And here you have a church that has been around since 1832 really saying, ‘We want to make sure that we are relevant today, in 2016, that we want to make sure that we have a church and a facility that can complement the needs of people today,'” Alexander says.

And historic preservation groups had their own frustrations. They say they warned that the designation application would be filed if the church applied for a raze permit, and expressed anger over the church’s rejection of a proposed land swap engineered by the National Park Service. Under the swap, The Beacon Center would be built on NPS land across the street from the church. But church officials said it would be too expensive, since they would have to redesign the entire building.

“All they have to do is put it across the street and we’ll be happy. I would support them,” says Loretta Neumann, a Ward 4 resident and president of the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington. “If they need a fundraising drive to help them raise money for something, I’d be the first to help them. I’m not against them, I’m not against the church, I’m just against the location of where they want to build this massive building.”

The battle comes to an end

But work continued towards making The Beacon Center a reality. A historic mitigation plan was drafted, which includes an archeological dig on the site for any Civil War-era artifacts. And church officials agreed to keep the majority of the church intact — the interior will be fully renovated — and give up one of the two levels of underground parking they had planned for the site.

And NPS will even get something out of it: space in the building for a visitors center for Fort Stevens.

Financing eventually came together, including a $17 million investment from D.C.’s Housing Production Trust Fund, which will help pay for the affordable housing units. Of the 99 being built, 91 will be set aside for renters making 60 percent or less of the Area Median Income. For a two-person household, that’s roughly $45,000 per year.

Despite the historic designation, Civil War buffs still feel the project is a mistake, and remain frustrated that church leaders rejected the land swap proposed by NPS.

“It’s one of the most historic sites in all of Washington,” says Neumann. “We have no problem with the church. It’s this massive development around the church.”

But for church leaders, the fight is now behind them. Speaking at the Friday groundbreaking, the Rev. Daniels sounded a note of God-given relief that The Beacon Center would be built.

“Over 12 years and over four mayoral administrations, there must be a God somewhere, and that God is here right now,” he said, to loud cheers from the crowd.

–wamu.org