Waiting for the slave ship United States near the New Orleans wharves in October 1828, Isaac Franklin may have paused to consider how the city had changed since he had first seen it from a flatboat deck 20 years earlier.

The New Orleans that Franklin, one of the biggest slave traders of the early 19th century, saw housed more than 45,000 people and was the fifth-largest city in the United States. Its residents, one in every three of whom was enslaved, had burst well beyond its original boundaries and extended themselves in suburbs carved out of low-lying former plantations along the river.

Population growth had only quickened the commercial and financial pulse of New Orleans. Neither the scores of commission merchant firms that serviced southern planter clients, nor the more than a dozen banks that would soon hold more collective capital than the banks of New York City, might have been noticeable at a glance. But from where Franklin stood, the transformation of New Orleans was unmistakable nonetheless.

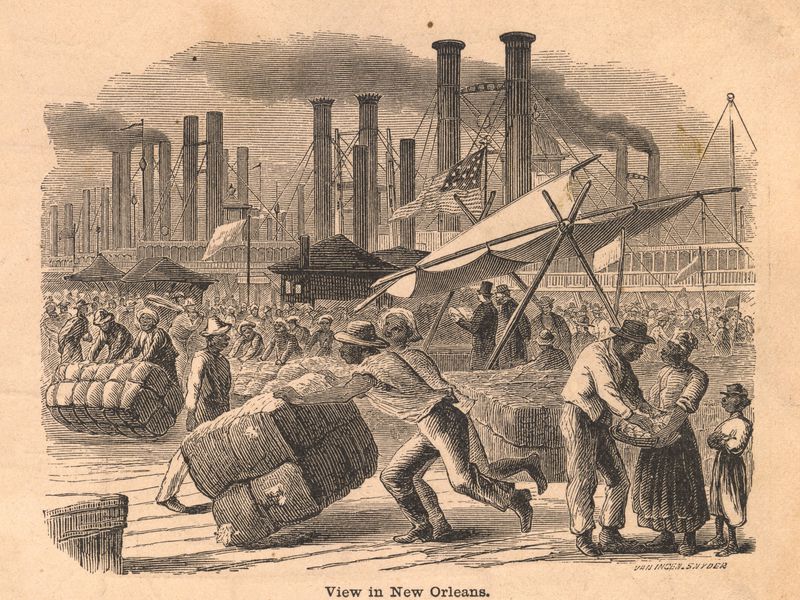

The pestilent summer was over, and the crowds in the streets swelled, dwarfing those that Franklin remembered. The change in seasons meant river traffic was coming into full swing too, and flatboats and barges now huddled against scads of steamboats and beneath a flotilla of tall ships. Arranged five or six deep for more than a mile along the levee, they made a forest of smokestacks, masts, and sails.

Coming and going from the forest were beef and pork and lard, buffalo robes and bear hides and deerskins, lumber and lime, tobacco and flour and corn. It was the cotton bales and hogsheads of sugar, stacked high on the levee, however, that really made the New Orleans economy hum. Cotton exports from New Orleans increased more than sevenfold in the 1820s. Pouring down the continental funnel of the Mississippi Valley to its base, they amounted by the end of the decade to more than 180 million pounds, which was more than half the cotton produced in the entire country. Nearly all of Louisiana’s sugar, meanwhile, left the state through New Orleans, and the holds of more and more ships filled with it as the number of sugar plantations tripled in the second half of the 1820s.

The city of New Orleans was the largest slave market in the United States, ultimately serving as the site for the purchase and sale of more than 135,000 people. In 1808, Congress exercised its constitutional prerogative to end the legal importation of enslaved people from outside the United States. But it did not end domestic slave trading, effectively creating a federally protected internal market for human beings. As Franklin stood in New Orleans awaiting the arrival of the United States, filled with enslaved people sent from Virginia by his business partner, John Armfield, he aimed to get his share of that business.

Just before dawn on October 2, Armfield had roused the enslaved he had collected in the compound he and Franklin rented on Duke Street in Alexandria. He had sorted the men, most of the women, and the older children into pairs. He had affixed cuffs and chains to their hands and feet, and he had women with infants and smaller children climb into a wagon. Then he had led them all three-quarters of a mile down to the Potomac River and turned them over to Henry Bell, captain of the United States, a 152-ton brig with a ten-man crew.

On October 21, after 19 days at sea, the United States arrived at the Balize, a dismal place where oceangoing ships often stopped to hire one of the boat pilots who resided there and earned a living ushering larger vessels upriver. As Henry Bell brought the United States around the last turn of the Mississippi the next day and finally saw New Orleans come into view, he eased as near as he could to the wharves, under the guidance of the steam towboat Hercules.

Franklin was not the only person waiting for slaves from the United States. The brig held 201 captives, with 149 sent by John Armfield sharing the misfortune of being on board with 5 people shipped by tavernkeeper Eli Legg to a trader named James Diggs, and 47 shipped by Virginia trader William Ish to the merchant firm of Wilkins and Linton. But none of them could collect what they came for until they took care of some paperwork.

In an effort to prevent smuggling, the 1808 federal law banning slave imports from overseas mandated that captains of domestic coastal slavers create a manifest listing the name, sex, age, height, and skin color of every enslaved person they carried, along with the shippers’ names and places of residence. One copy of the manifest had to be deposited with the collector of the port of departure, who checked it for accuracy and certified that the captain and the shippers swore that every person listed was legally enslaved and had not come into the country after January 1, 1808. A second copy got delivered to the customs official at the port of arrival, who checked it again before permitting the enslaved to be unloaded. The bureaucracy would not be rushed.

At the Customs House in Alexandria, deputy collector C. T. Chapman had signed off on the manifest of the United States. At the Balize, a boarding officer named William B. G. Taylor looked over the manifest, made sure it had the proper signatures, and matched each enslaved person to his or her listing. Finding the lot “agreeing with description,” Taylor sent the United States on its way.

In New Orleans, customs inspector L. B. Willis climbed on board and performed yet another inspection of the enslaved, the third they had endured in as many weeks. Scrutinizing them closely, he proved more exacting than his Balize colleague. Willis cared about the details. After placing a small check mark by the name of every person to be sure he had seen them all, he declared the manifest “all correct or agreeing excepting that” a sixteen-year-old named Nancy, listed as “No. 120” and described as “black” on the manifest, was in his estimation “a yellow girl,” and that a nine-year-old declared as “Betsey no. 144 should be Elvira.”

Being examined and probed was among many indignities white people routinely inflicted upon the enslaved. Franklin was no exception. Appraising those who were now his merchandise, Franklin noticed their tattered clothing and enervated frames, but he liked what he saw anyway. The vast majority were between the ages of 8 and 25, as Armfield had advertised in the newspaper that he wanted to buy. Eighty-nine of them were boys and men, of whom 48 were between 18 and 25 years old, and another 20 were younger teens. The 60 women and girls were on average a bit younger. Only eight of them were over 20 years old, and a little more than half were teenagers. It was a population tailored to the demands of sugarcane growers, who came to New Orleans looking for a demographically disproportionate number of physically mature boys and men they believed could withstand the notoriously dangerous and grinding labor in the cane fields. They supplemented them with girls and women they believed maximally capable of reproduction.

Now that he had the people Armfield had sent him, Franklin made them wash away the grime and filth accumulated during weeks of travel. He stripped them until they were practically naked and checked them more meticulously. He pored over their skin and felt their muscles, made them squat and jump, and stuck his fingers in their mouths looking for signs of illness or infirmity, or for whipping scars and other marks of torture that he needed to disguise or account for in a sale.

Franklin had them change into one of the “two entire suits” of clothing Armfield sent with each person from the Alexandria compound, and he gave them enough to eat so they would at least appear hardy. He made them aware of the behavior he expected, and he delivered a warning, backed by slaps and kicks and threats, that when buyers came to look, the enslaved were to show themselves to be spry, cheerful and obedient, and they were to claim personal histories that, regardless of their truth, promised customers whatever they wanted. It took time to make the enslaved ready to retail themselves—but not too much time, because every day that Franklin had to house and feed someone cut into his profits.

Exactly where Franklin put the people from the United States once he led them away from the levee is unclear. Like most of his colleagues, Franklin probably rented space in a yard, a pen, or a jail to keep the enslaved in while he worked nearby. He may have done business from a hotel, a tavern, or an establishment known as a coffee house, which is where much of the city’s slave trade was conducted in the 1820s. Serving as bars, restaurants, gambling houses, pool halls, meeting spaces, auction blocks, and venues for economic transactions of all sorts, coffee houses sometimes also had lodging and stabling facilities. They were often known simply as “exchanges,” reflecting the commercial nature of what went on inside, and itinerant slave traders used them to receive their mail, talk about prices of cotton and sugar and humans, locate customers, and otherwise as offices for networking and socializing.

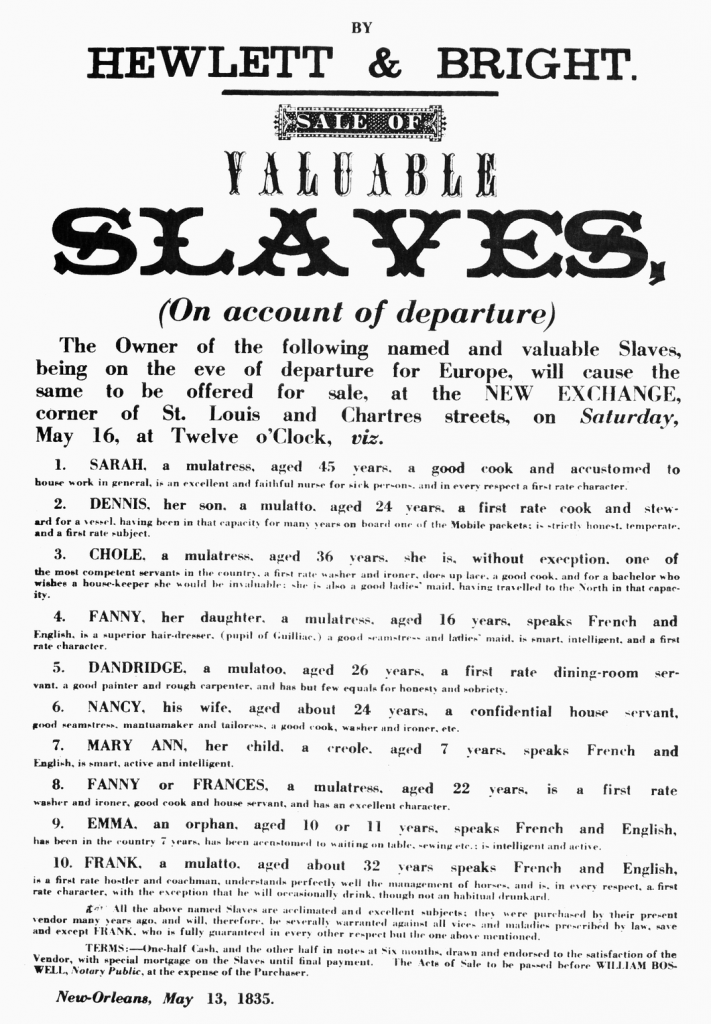

Broadside announcing the sale of slaves at New Orleans, Louisiana, 1835.

Franklin is especially likely to have spent time at Hewlett’s Exchange, which held slave auctions daily except on Sundays and which was the most important location of the day for the slave trade. Supply met demand at Hewlett’s, where white people gawked and leered and barraged the enslaved with intrusive questions about their bodies, their skills, their pasts. Hewlett’s was where white people came if they were looking to buy slaves, and that made it the right place for a trader like Franklin to linger. Hewlett’s was also proximate to the offices of many of the public functionaries required under Louisiana’s civil law system known as notaries. No slave sale could be entirely legal in Louisiana unless it was recorded in a notarial act, and nearly all of the city’s dozen or so notaries could be conveniently found within a block of two of Hewlett’s Exchange.

Before the year was out, Franklin would conduct 41 different sales transactions in New Orleans, trading away the lives of 112 people. He sold roughly a quarter of those people individually. He sold others in pairs, trios, or larger groups, including one sale of 16 people at once. Felix DeArmas and another notary named William Boswell recorded most of the transactions, though Franklin also relied on the services of seven other notaries, probably in response to customer preferences.

In a few instances, Franklin sold slaves to free people of color, such as when he sold Eliza and Priscilla, 11 and 12 years old, to New Orleans bricklayer Myrtille Courcelle. But nearly all of Franklin’s customers were white. Some were tradesmen—people like coach and harness maker Charles Bebee, goldsmith Jean Claude Mairot, and druggist Joseph Dufilho. Others were people of more significant substance and status. Franklin sold two people to John Witherspoon Smith, whose father and grandfather had both served as presidents of the College of New Jersey, known today as Princeton University, and who had himself been United States district judge for Louisiana. Franklin sold a young woman named Anna to John Ami Merle, a merchant and the Swedish and Norwegian consul in New Orleans, and he sold four young men to François Gaiennié, a wood merchant, city council member, and brigadier general in the state militia. One of Louise Patin’s sons, André Roman, was speaker of the house in the state legislature. He would be elected governor in 1830.

We rarely know what Franklin’s customers did with the people they dispersed across southern Louisiana. Buyers of single individuals probably intended them for domestic servants or as laborers in their place of business. Many others probably put the enslaved they bought to work in the sugar industry. Few other purposes explain why sugar refiner Nathan Goodale would purchase a lot of ten boys and men, or why Christopher Colomb, an Ascension Parish plantation owner, enlisted his New Orleans commission merchant, Noel Auguste Baron, to buy six male teenagers on his behalf.

Franklin mostly cared that he walked away richer from the deals, and there was no denying that. Gross sales in New Orleans in 1828 for the slave trading company known as Franklin and Armfield came to a bit more than $56,000. Few of John Armfield’s purchasing records have survived, making a precise tally of the company’s profits impossible. But several scholars estimate that slave traders in the late 1820s and early 1830s saw returns in the range of 20 to 30 percent, which would put Franklin and Armfield’s earnings for the last two months of 1828 somewhere between $11,000 and $17,000. Equivalent to $300,000 to $450,000 today, the figure does not include proceeds from slave sales the company made from ongoing operations in Natchez, Mississippi.

Even accounting for expenses and payments to agents, clerks, assistants, and other auxiliary personnel, the money was a powerful incentive to keep going.

Isaac Franklin and John Armfield were men untroubled by conscience. They thought little about the moral quality of their actions, and at their core was a hollow, an emptiness. They understood that Black people were human beings. They just did not care. Basic decency was something they really owed only to white people, and when it came down to it, Black people’s lives did not matter all that much. Black lives were there for the taking. Their world casts its long shadow onto ours.

Excerpted from The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America by Joshua D. Rothman. Copyright © 2021. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

–smithsonianmag.com