Civil War medicine did not exist in a vacuum only on battlefields and in hospitals. It began long before armies met in combat or men became ill; it began in classrooms, books, and lectures as surgeons and doctors learned and improved their skills and disseminated knowledge. Nor did it end on the battlefield, as surgeons took detailed records to inform future practice. Perhaps most importantly, it continued on in the form of successfully treated soldiers. Though they survived their wounds or diseases, they carried the side effects of the injury and the treatment for the rest of their lives, sometimes well into the 1900s. While some veterans carried bullet fragments in their bodies or vital organs weakened by illness or disease into civilian life, the legacy of Civil War medicine was rarely more visible than in the form of veterans who had limbs amputated.

John F. Chase began his service in April 1861, joining Company B of the Third Maine Infantry for a short term of service. Though he claimed to have been briefly captured at First Manassas, he escaped and rejoined the unit, going home and mustering out at the end of the term. He reenlisted into the Fifth Maine Battery that fall and was present with them through battles that dwarfed First Manassas in scale. Chase later received the Medal of Honor for his actions at Chancellorsville, where the citation states his deeds: “Nearly all the officers and men of the battery having been killed or wounded, this soldier with a comrade continued to fire his gun after the guns had ceased. The piece was then dragged off by the two, the horses having been shot, and its capture by the enemy was prevented.”[1]

That summer he was with the battery as it moved through Maryland and Pennsylvania towards Gettysburg. The battery was stationed north of the Lutheran Seminary on July 1, 1863 until forced back through town when the US First Corps retreated. On July 2, Chase and the battery were placed along Steven’s Knoll and heavily engaged against the Confederate’s evening assaults on East Cemetery Hill. While the battery fired canister into the flanks of the advancing foe, Confederate artillery opened up with counter-battery fire. One shell exploded near Chase, and he later stated that “forty-eight pieces of it entered my body.” While Chase believed it was Confederate fire that struck him down, others have set forth the possibility that a shell Chase was loading into his gun prematurely detonated. As recorded in Walter Beyer and Oscar Keydel’s 1901 book Deeds of Valor: How America’s Heroes Won the Medal of Honor, Chase claimed that the first words he said when he regained consciousness while being carted away from the field were “Did we win the battle?”[2]

Chase was taken to the Isaac Lightner farm for treatment, where the surgeons attended to other wounded first, believing that he was certain to die. Performing a form of triage, they wanted to expend their efforts on patients they believed they could save. He lived and was eventually taken into to house to heal. From there he was transferred to the hospital at the Lutheran Seminary (now the excellent Seminary Ridge Museum). Chase’s right arm was amputated on July 8, as the severe damage to bone, muscle, and flesh from the shell fragments made it impossible to heal. At some point he may have passed through Camp Letterman, as a case book from that hospital records his injury as “comp[ound] fract[ure] of Right Arm with amputation- loss of Left Eye and Flesh wounds” and notes his struggles with erysipelas, which is a skin infection, and diarrhea.[3] From there he was transferred to a final hospital in Philadelphia. Throughout all this time, except for perhaps when surgeons believed his death a certainty, he was receiving care, wound cleaning, bandage dressings, and wholesome meals to the best of the knowledge and ability of the medical staff.

Veterans at the 5th Maine Battery’s monument on Steven’s Knoll at Gettysburg. It is likely that John Chase is on the left of the group of veterans. Maine State Archives.

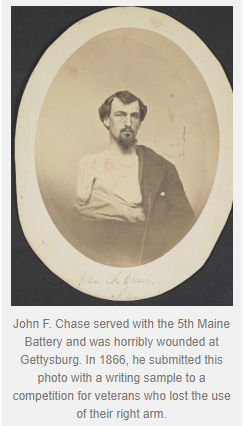

While the image of him without an arm and with visible wounds complete with a false eye is one that evoked shock and pity both in the 1860s and today, rather than a portrayal of failure it actually displays the success of medical practice. Amputations were a necessary procedure that modern Americans often incorrectly view as an unnecessary brutality. Though the wound cost Chase an eye and an arm, the improved methods of Civil War medicine that were in effect by 1863 fought to make sure that it would not cost Chase his life.

He was discharged in November 1863, and went home to Augusta, Maine. He married, had children, and worked as an inventor registering patents. Late in life, he moved to Florida and set forth on various business ventures. Throughout this, he drew a pension to support himself and his family but certainly stayed active. He also gleaned extra income through the sale of images of himself and serving as an occasional guide for the cyclorama of the battle of Gettysburg. Still, the wound and its effects followed him the rest of his life. In addition to the visible difficulties stemming from the loss of his right arm and left eye, postwar medical evaluations stated he suffered from poor eyesight in his remaining eye, pain in his head, a shortness of breath stemming from scar tissue in the lung, and his right chest which is shown heavily damaged in photos was noted as “one vast, oozing scar.”[4]

A postwar image of John Chase wearing a uniform of the Grand Army of the Republic veterans organization. Gulfport Historical Society.

In 1866, Chase wrote about his service, his wounding, and his recovery. Submitting to a writing contest for veterans, what his account lacks in correct spelling it makes up for in spirit. He summarized his Gettysburg injury, stating: “I lost my right arm near the shoulder, and left eye, and have forty other scars upon my brest and shoulder caused by peaces of fragments of a Spherical case shot, at the battle of Gettersburg July the second 1863.” Humbly, he closed with the note “My eye sight is rather poor that is the reason why I do not wright more or better.” He attached an image, shown earlier in this article, so that the scale of his injuries were obvious to the reader.[5]

John Chase died in 1914 in St. Petersburg, Florida. He was 20 years old when he was wounded at Gettysburg and lived for 51 years after his wound. Though he had lived an active and productive life after the war, he had also lived over 2/3rds of his life as a visible testament to the impact of Civil War medicine.

–emergingcivilwarcom

A CDV of Chase telling his story and showing him as an example of what the war cost American soldiers. Maine State Archives. https://digitalmaine.com/arc_civilwarportraits/782/

[1] Congressional Medal of Honor Society. https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/john-f-chase. Chase’s Medal of Honor is now displayed at the Chancellorsville Visitor Center at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

[2] Henry Janes, Camp Letterman Hospital Case Ledger, 1863, Special Collections, University of Vermont, transcribed by Jonathan Tracey, compiled and edited by John Heiser, Gettysburg National Military Park Library, 159.

[3] Walter F. Beyer and Oscar F. Keydel, Deeds of Valor: How America’s Heroes Won the Medal of Honor, Vol. 1 (Detroit: The Perrien-Keydel Company, 1901), 146.

[4] Bert Barnett, “A Past So Fraught with Sorrow”, Gettysburg: The End of the Campaign and Battle’s Aftermath Papers from the 2010 Seminar Gettysburg National Military Park, 2010, 126-127. http://npshistory.com/series/symposia/gettysburg_seminars/13/essay6.pdf

[5] William Oland Bourne Papers, Entry 223, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss13375028/