In Arlington National Cemetery’s Section 1, you’ll find a diverse mix of grave markers, from basic white headstones to massive, ornate monuments commissioned by generals and other U.S. leaders. Among them, you’ll also find the graves of 23 pioneering female Civil War nurses.

In the 19th century, nursing was a male profession. But by the middle of the century, U.S. leaders were intrigued by what women like Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole were doing overseas for British soldiers during the Crimean War. So, when the Civil War began, Congress authorized the hiring of female nurses to assist the Army. Other non-official nurses volunteered with local units, too, having been recruited by state or local officials. Many more followed their husbands to war to help soldiers in their units.

Very few of these nurses had professional medical training because it simply wasn’t available to women back then. Instead, they had on-the-job training on how to care for injured and ill patients.

“They would feed, clothe and wash soldiers, do their best to make them physically comfortable, and they would tend to their mental and spiritual needs,” explained Army historian Kathy Fargey, who recently gave a public tour of the Civil War nurses’ area of Arlington’s Section 1 to commemorate Women’s History Month. “They helped [soldiers] write letters, and they would read to them, talk with them and pray with them.”

During the tour, Fargey highlighted five women buried in Arlington’s Section 1 who helped set the stage for future generations of female nurses.

Anna Platt

Anna Platt was born in 1820 in New York. She made her way south in February 1863 to help at Armory Square Hospital, a 1,000-bed war hospital in Washington, D.C., where she stayed through the end of the war.

Nurses at the hospital who documented their work at the Armory said they started their days at 6 a.m., feeding and giving patients medicine throughout the day, as well as changing their bandages and offering them comfort. They also arranged evening entertainment.

“Anna had a friend who sent her an accordion, so she played accordion music for the soldiers in the evening,” Fargey said. “They all had singing and music and public readings. Then the night watchers would finally arrive at 8:45 p.m. to take over from the nurses.”

Platt’s pension records were submitted to Congress in 1891. According to those records, the Army nurse suffered “a severe attack of typhoid and brain fever” while working at Armory Square, “from the effects of which she has never fully recovered.” Platt is one of 21 of the nurses buried in Arlington’s Section 1 to receive what was called an invalid’s pension — an antiquated term for a disabled veteran’s pension.

Platt died in November 1898. She was the first Civil War nurse to be buried in Arlington specifically because of her wartime service.

Adelaide Spurgeon

Adelaide Spurgeon was born in England in 1829 and immigrated to the U.S. around 1860. She lived in New York City and was recruited in the early days of the war to go to D.C. to help as an Army nurse. When she arrived in Washington, she discovered there was only one hospital in which to work, and it was for smallpox patients.

“The other nurses said, ‘No thanks,’ and Adele was the only one to say, ‘I’ll take the risk’,” Fargey said.

Spurgeon became well-known for her skills. According to Fargey’s research, the nurse complained of the lack of medical supplies and the quality of food at the hospital, so she went back to New York and enlisted her friends to help her collect better supplies, which she brought back for the patients. Spurgeon eventually became sick herself, being diagnosed with blood poisoning at some point during the war. However, that led to a second career for her.

“Adele had to quit nursing when she got sick but took a job with the Army Provost Marshal as an undercover agent,” Fargey said, referring to the wartime bureau that dealt with enlistment and desertion issues. “She would go to places where soldiers gathered and she would find out who was away from their company without leave, or who was a deserter.”

Spurgeon also received an invalid’s pension for her sacrifices. She died on March 4, 1907.

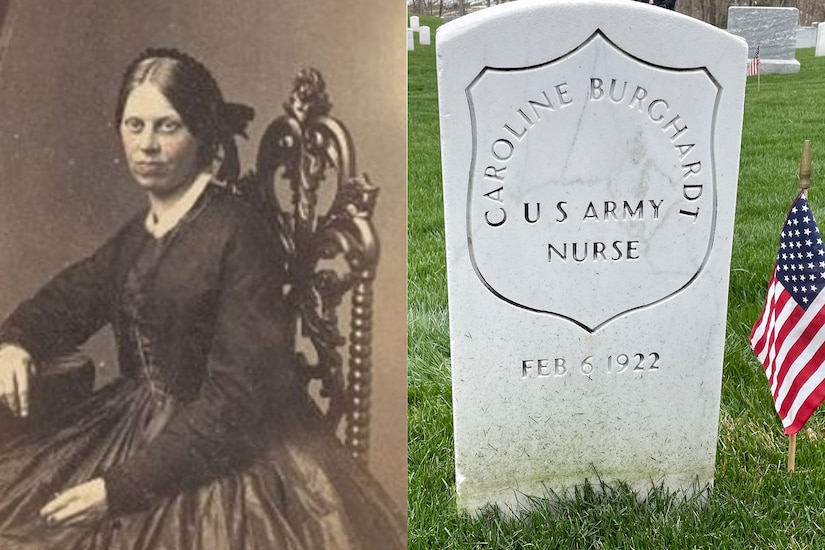

Caroline Burghardt

Born in 1833 in Massachusetts, Caroline Burghardt was a distant cousin of Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and joined the war effort in June 1861. Since she was under 30, which was the age requirement to become an Army nurse, Burghardt had to get a waiver from a doctor who endorsed her. However, unlike most female nurses of the time, she had received some training at Bellevue Hospital in New York.

Burghardt worked at several D.C.-area hospitals before travelling to battlefield sites, including Gettysburg and Antietam. During her years of service, she contracted smallpox and yellow fever, which allowed her to receive an invalid’s pension as well. Dorothea Dix, the superintendent of Army nurses and ardent advocate for the work of female nurses, said Burghardt earned the respect and confidence of surgeons and prolonged the lives of hundreds of soldiers.

After the war, Burghardt attended Howard University — one of few schools that allowed female medical students — and earned a medical degree in 1878 that allowed her to practice as a doctor in D.C. for many years. She also worked for the U.S. Treasury and Commerce departments for more than 50 years, retiring in 1920 just before she turned 87.

Burghardt died on Feb. 6, 1922, at age 88.

Sarah E. Thompson

Sarah E. Thompson was born Feb. 11, 1838, in Greene County, Tennessee. Unlike Platt, Spurgeon and Burghardt, she didn’t begin her Civil War service as a nurse. When she was about 16, she married Sylvanius Thompson and they had two daughters. When her husband joined the Union Army as a recruiter, she worked alongside him, even though they were in a predominantly rebel area.

In 1864, Thompson’s husband was ambushed and killed by a Confederate soldier — an act that only made her work harder for the Union Army. One night, when Confederate Gen. John H. Morgan and his soldiers spent a night in Greeneville, Tennessee, Thompson managed to sneak away, find Union forces and bring them back to deal with Morgan. She’s given credit for pointing out Morgan, who was hiding from Union troops behind a garden fence, before he was shot and killed.

After that incident, Thompson served as an Army nurse until the end of the war. According to Duke University’s Special Collections Library, she then supported herself and her daughters by giving lectures in northern cities about her experiences during the war.

Thompson went on to marry two more times and have two more children. When her third husband died, she took several temporary jobs with the federal government and fought to get an invalid’s pension, which she was eventually granted in 1897.

Thompson died on April 21, 1909, after being struck by a streetcar in Washington.

Emma Southwick Brinton

Emma Southwick Brinton was born in 1834 in Massachusetts. During the Civil War, she first worked as an Army nurse in the Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, before working at Armory Square Hospital in D.C. Records show she was one of three nurses who were sent to Fredericksburg, Virginia, to care for 10 buildings filled with wounded men. While there, the nurses slept on the floor in the slave quarters of one of the houses.

At one point, due to the unsanitary conditions in which she often worked, Brinton contracted typhoid fever. She was sent back to Massachusetts to recover. Afterward, she returned to D.C. and various battlefields to continue nursing. She also received an invalid’s pension.

After the war, Brinton married a Civil War surgeon. When he died in 1894, she became a newspaper correspondent, Fargey said, as well as an international traveler. Newspapers said she crossed the Atlantic more than 20 times and visited several World’s Fairs.

Brinton died on Feb. 25, 1922, at age 88. She was the last of the 23 female nurses to be buried in Arlington’s Section 1.

The Defense Department honors all of these pioneers and their contributions in setting the stage for future nurses and medical aides.