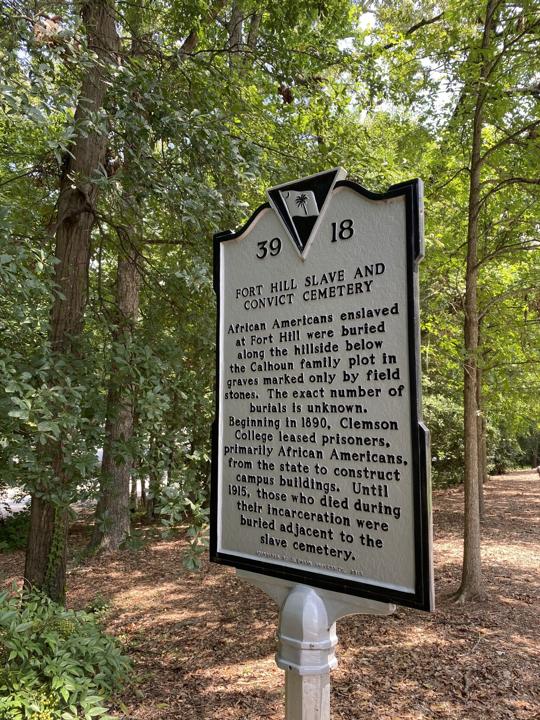

CLEMSON, S.C. – Temporary pink and white flags now dot the western hill of Clemson University’s Woodland Cemetery, marking where researchers have recently discovered that the bodies of hundreds of Black slaves and indentured convicts are among the polished granite headstones of the privileged buried in the shadow of John C. Calhoun’s Fort Hill plantation.

The announcement Monday comes just as a team of university researchers was already making progress in honoring the graves of the people who essentially built the university from the Antebellum era into its founding with a land grant from Thomas Green Clemson in 1889.

The researchers discovered more than they bargained for when they found the scope of unmarked graves extends beyond a known area on the south end of Calhoun’s plantation.

The graves were found using ground-penetrating radar technology to scan the western slope, guided in part by “field stones” placed inconsistently more than a century ago to mark where bodies were buried. The presence of stones can mean a grave exists or the stone has been displaced by erosion.

The scan found 215 instances of disturbed ground about five feet below that would indicate grave sites, including 160 on the 2-acre western slope, said Paul Anderson, the university historian leading the research effort.

Even along a paved walking path, orange circles are painted to mark graves believed to be beneath.

James Bostic, a former member of Clemson University’s Board of Trustees, walks a path in the Woodland Cemetery marked with orange circles to signal where unmarked graves of indentured laborers lie beneath.

The research will continue, and the work will likely find more graves in the coming weeks further down the hill, where thick underbrush will have to be removed to scan for more, Anderson said.

The university has created a website to document the work, which even in its placeholder status provides deep context. A closing note speaks to an investigation into how so many graves could have been moved or forgotten as other, more privileged dead took their place.

“We know, right now, that we do not know more,” the website’s closing note states. “We do not know what, in fullness, happened. We do not know the fullness of why it happened. But what we know now is disturbing enough to raise significant and uncomfortable questions that will likely take several years of research to answer.”

The discovery comes as the history of John C. Calhoun has come under increased scrutiny in the wake of protests across the U.S. over systemic racism following the death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer.

Calhoun, a preeminent South Carolina statesman and former U.S. vice president, extolled slavery as a “positive good.”

The university renamed the Calhoun Honors College to Clemson University Honors College in early June. Later that month, the statue of Calhoun that towered over Marion Square in downtown Charleston was removed.

Long-simmering pressure continues to rename Clemson’s iconic Tillman Hall, named after avowed white supremacist and former state governor Ben “Pitchfork” Tillman.

The state’s Heritage Act, which prevents the altering of monuments, stands in the way. The state Attorney General has asked the South Carolina Supreme Court to issue an opinion on whether the act is Constitutional.

Dating back as far as the end of World War II, documents show the university believed there could be as many as 250 enslaved Black workers and convicted buried in the cemetery.

The school’s building and grounds committee in March 1946 voted “to recommend that some type of permanent marker be established on Cemetery Hill to indicate this colored graveyard.”

But it is a 1960 court order that shows the university knew that graves existed on the western slope, where just through the trees the south stands of Death Valley rise equal to the hill, and sought to move them to a current collection on the south side.

In that court order, the same year Clemson desegregated, the university references “unmarked field stones set in no regular pattern are thought by legend and ancient report to mark the graves of deceased Negro slaves or of prisoner laborers at one time employed in the construction of the works of the College.”

The law required next of kin be notified but in the order the university said it was impossible to know who was buried and where.

A plaque at the entrance of Clemson University’s Woodland Cemetery marks the history of indentured Black laborers buried in unmarked graves.

The remains of some Black laborers were moved to a south-side location known as the “Site of Unknown Burials” where today’s researchers were set to scan.

The south side graves were within a fenced area that in February had been littered and unmaintained until two Clemson students brought the condition to the attention of Dr. Rhondda Thomas, a Clemson professor who focuses on early African-American literature and culture, and leader of the “Call My Name” Black history project.

University historians, with the support of senior Clemson leadership, were in the process of planning a suitable memorial. Then, the day before the radar scan was to be performed, they discovered the 1960 order.

The effort to locate more laborer graves dates back to 1992, then again another effort in the early 2000s. While researchers then were convinced the graves existed, neither effort yielded definitive information.

“My research shows that Black lives hardly mattered at all at Clemson until after desegregation, and the discovery we made in this burial ground tells me that Black deaths mattered even less,” Thomas said Monday. “The thing that I found was that Black labor mattered the most on this land where Clemson was built.”

Now, the discovery work will continue expeditiously, as leaders of the project scour historical records and engage members of the community to try to determine the identities of who among the Black laborers might be buried in the cemetery.

“We will continue working on this as long as it takes to get the answers that we need,” Thomas said. “It’s going to take a long time to actually get to the bottom of this.”

What is unclear at this point is how to move forward with an awkward dilemma: Influential university figures are buried with marked headstones, and other plots are reserved but unfilled, while the unmarked graves of indentured Black workers lie beneath.

“We are working on a plan to deal with that,” Thomas said. “We don’t have an answer for that right now.”

The research and restoration work has the support of the highest level Clemson leaders.

“We are committed to taking all the critically important actions to enhance these grounds, preserve these grave sites and to ensure the people buried there are properly honored and respected,” said Smyth McKissick, chairman of the university’s Board of Trustees.

–postandcourier.com