The Southern Campaign of the American Revolution has often been depicted in literature in a glamorous and romantic fashion with emphasis on the exploits of native-son militia in each colony. Granted, brave and daring militia leaders played a crucial role in the War for Independence, but they were part of a much larger and oft-neglected drama-a bloody civil war often pitting neighbor against neighbor — evident in the South, especially in the Carolina backcountry. The lower South, a region more often associated with the American Civil War of 1860, was ravaged as no other section. The war in the South went far in deciding the final Patriot victory.

This depiction of the 1781 Battle of Cowpens, a uniformed Bi-Racial Soldier, on (left), firing his pistol and saving the life of Colonel William Washington, (on white horse in center), from an 1845 painting, by artist, William Ranney

The Southern Campaign began with British concern over the course of the war in the North. Failure at Saratoga, fear of French intervention, and over-all failure to bring the rebels to heel persuaded British military strategists to turn their attention to the South. Some in Britain even suggested that New England, that hotbed of sedition, was a lost cause anyway and not worth the effort, temporarily or even permanently. The British did have some success in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, but failed to consolidate their efforts. They appeared, in fact, to lack any over-all strategy to crush the rebels.

Early on, British military strategists saw the South as a Loyalist stronghold. There were the Highland Scots of the Cape Fear Region in North Carolina, strong Anglicans in coastal areas, those with grudges against colonial governments, Indian traders, mercantilists, late-arriving immigrants, and those running from the law – all having reason to remain loyal to the Crown. The South, however, was more sharply divided than British estimates. The strengthening of Loyalist sentiment and consequent Patriot hostility resurrected age-old animosities and loyalties as regions, individuals, or even families chose sides. Consequently, the war took on the nature of a violent civil war. Raids, murders, and reprisals became the order of the day. Even, at times, families were fractured as members differed over the war. Plantations were plundered and crops, destroyed. With civil government virtually collapsed, violence and hatred grew to the point of hope for victory as the only solution. Forced to choose between collaboration or rebellion, many Americans chose the latter. More and more, guerilla warfare replaced orthodox fighting.

From the beginning, the British were undaunted. With such perceived Loyalist support, British victory over the rebels was to be an easy one – a quick expedition south to restore the “King’s Friends” to power over Patriots who had earlier wrested control from royal governors. With the Georgia and South Carolina under firm Loyalist control, red-coated British troops could then subdue North Carolina and Virginia. British General Henry Clinton, in his memoirs, The American Rebellion, stated that the British goal in the South “was to support the Loyalists and restore the authority of the King’s government”. Intense British political pressure emphasized Loyalist-related strategies as a means of victory. Additionally, some British strategists envisioned a “Chesapeake squeeze” in which British forces in the North would drive south toward Virginia, creating a pincers movement and trapping American forces. The Chesapeake, wrested from American control, would serve as a base for British naval operations.

The British had additional motives for the South. Southern agricultural products — notably tobacco, rice, and indigo — were important to British mercantile interests. British strategists saw the Carolinas, Georgia, East Florida, the Bahamas and Bermuda as an important post-war trade grouping and an integral part of the West Indies sugar trade. Savannah and, more importantly, Charleston would fit well into such a grouping. Charleston was coveted, especially, as the most important southern port and the fourth largest and richest city in North America.

The fall of Charleston on May 12, 1780, was perhaps the worst defeat Americans suffered during the entire Revolution. Subsequent British victories at the Waxhaws, Camden, and Fishing Creek eliminated much of the southern Continental army and made the British confident that the South was theirs. Events in the North and South led to a feeling of Patriot desperation by the summer of 1780.

The tide of battle was soon to turn, however, in a sequence of events. First, overmountain men defeated forces under Patrick Ferguson at Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780. General Cornwallis, in command in the South, abruptly stopped his push into North Carolina and fell back to South Carolina to protect its western borders.

The Battle of Cowpens1, January 17, 1781, took place in the latter part of the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution and of the Revolution itself. It became known as the turning point of the war in the South, part of a chain of events leading to Patriot victory at Yorktown2 The Cowpens victory was won over a crack British regular army3 and brought together strong armies and leaders who made their mark on history.

From the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge4 on, the British had made early and mostly futile efforts in the South, including a failed naval expedition to take Charleston in 1776. Such victories boosted Patriot morale and blunted British efforts, but, by 1779-80, with stalemate in the North, British strategists again looked south. They came south for a number of reasons, primarily to assist Southern Loyalists5 and help them regain control of colonial governments, and then push north, to crush the rebellion6. They estimated that many of the population would rally to the Crown.

In 1779-80, British redcoats indeed came South en masse, capturing first, Savannah7 and then Charleston8 and Camden 8A in South Carolina, in the process, defeating and capturing much of the Southern Continental Army9. Such victories gave the British confidence they would soon control the entire South, that Loyalists would flock to their cause. Conquering these population centers, however, gave the British a false sense of victory they didn’t count on so much opposition in the backcountry10. Conflict in the backcountry, to their rear, turned out to be their Achilles’ heel.

The Southern Campaign, especially in the backcountry, was essentially a civil war as the colonial population split between Patriot and Loyalist. Conflict came, often pitting neighbor against neighbor and re-igniting old feuds and animosities. Those of both sides organized militia, often engaging each other. The countryside was devastated, and raids and reprisals were the order of the day.

Into this conflict, General George Washington sent the very capable Nathanael Greene to take command of the Southern army. Against military custom, Greene, just two weeks into his command, split his army, sending General Daniel Morgan southwest of the Catawba River to cut supply lines and hamper British operations in the backcountry, and, in doing so “spirit up the people”.

General Cornwallis, British commander in the South, countered Greene’s move by sending Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton to block Morgan’s actions. Tarleton was only twenty-six, but he was an able commander, both feared and hated – hated especially for his victory at the Waxhaws.11 There, Tarleton was said to have continued the fight against remnants of the Continental Army trying to surrender. His refusal, tradition says, of offering no quarter, led to the derisive term “Tarleton’s Quarter”.

These events set the stage for the Battle of Cowpens. On January 12, 1781, Tarleton’s scouts located Morgan’s army at Grindal Shoals on the Pacolet River12 in South Carolina’s backcountry and thus began an aggressive pursuit. Tarleton, fretting about heavy rains and flooded rivers, gained ground as his army proceeded toward the flood-swollen Pacolet. As Tarleton grew closer, Morgan retreated north to Burr’s Mill on Thicketty Creek.13 On January 16, with Tarleton reported to have crossed the Pacolet and much closer than expected, Morgan and his army made a hasty retreat, so quickly as to leave their breakfast behind. Soon, he intersected with and traveled west on the Green River Road. Here, with the flood-swollen Broad River14 six miles to his back, Morgan decided to make a stand at the Cowpens, a well-known crossroads and frontier pasturing ground.

The term “cowpens“15, endemic to such South Carolina pastureland and associated early cattle industry, would be etched in history. The field itself was some 500 yards long and just as wide, a park-like setting dotted with trees, but devoid of undergrowth, having been kept clear by cattle grazing in the spring on native grasses and peavine16.

There was forage17 at the Cowpens for horses, and evidence of free-ranging cattle for food. Morgan, too, since he had learned of Tarleton’s pursuit, had spread the word for militia18 units to rendezvous at the Cowpens. Many knew the geography some were Overmountain men who had camped at the Cowpens on their journey to the Battle of Kings Mountain.19 Camp was made in a swale between two small hills, and through the night Andrew Pickens’ militia drifted into camp. Morgan moved among the campfires and offered encouragement; his speeches to militia and Continentals alike were command performances. He spoke emotionally of past battles, talked of the battle plan, and lashed out against the British. His words were especially effective with the militia the “Old Waggoner“20 of French and Indian War days and the hero of Saratoga21, spoke their language. He knew how to motivate them even proposing a competition of bravery between Georgia and Carolina units. By the time he was through, one soldier observed that the army was “in good spirits and very willing to fight”. But, as one observed, Morgan hardly slept a wink that night.

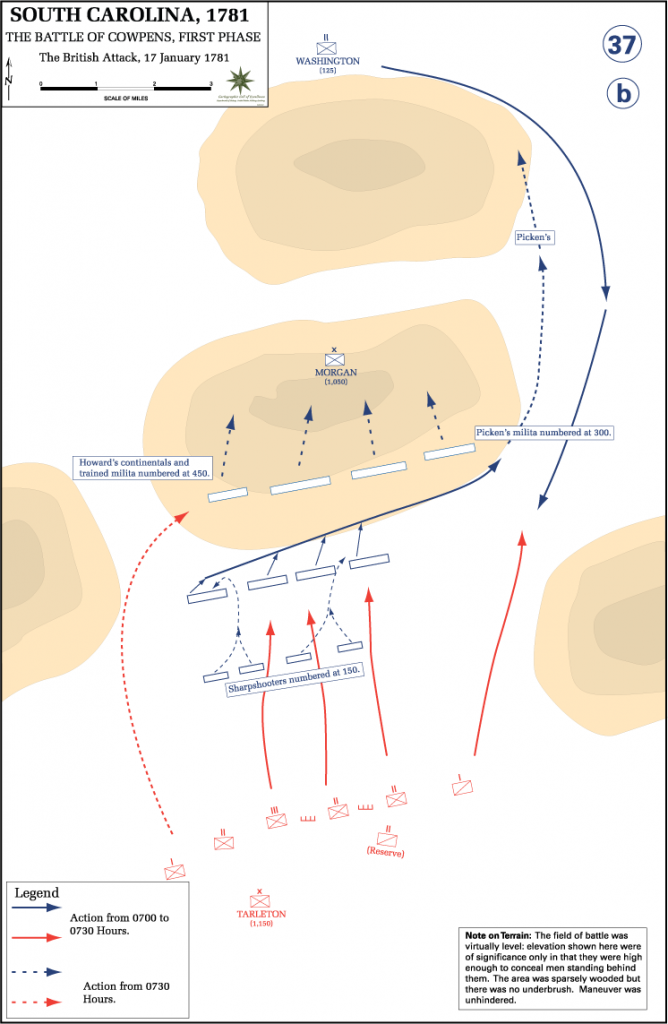

Dawn at the Cowpens on January 17, 1781, was clear and bitterly cold. Morgan, his scouts bearing news of Tarleton’s approach, moved among his men, shouting, “Boys, get up! Benny’s22 coming! Tarleton, playing catch up, and having marched his army since two in the morning, ordered formation on the Green River Road for the attack. His aggressive style was made even now more urgent, since there were rumors of Overmountain men on the way, reminiscent of events at Kings Mountain. Yet he was confident of victory: he reasoned he had Morgan hemmed in by the Broad, and the undulating park-like terrain was ideal for his dragoons23. He thought Morgan must be desperate, indeed, to have stopped at such a place. Perhaps Morgan saw it differently: in some past battles, Patriot militia had fled in face of fearsome bayonet charges – but now the Broad at Morgan’s back could prevent such a retreat. In reality, though, Morgan had no choice – to cross the flood-swollen Broad risked having his army cut down by the feared and fast-traveling Tarleton.

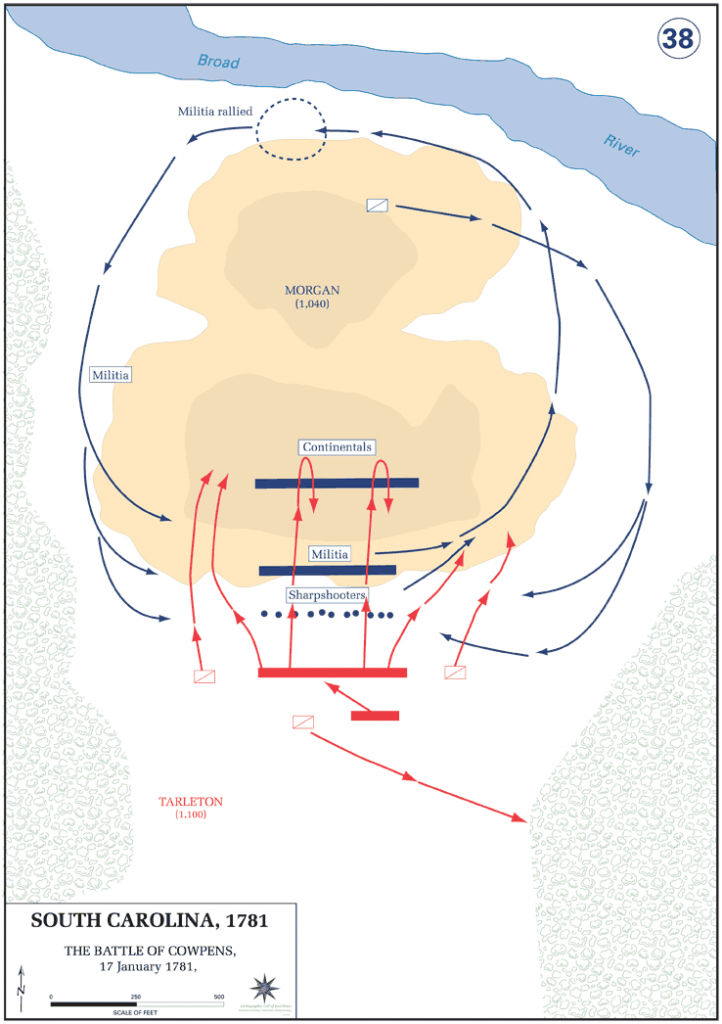

Tarleton pressed the attack head on, his line extending across the meadow, his artillery in the middle, and fifty Dragoons on each side. It was as if Morgan knew he would make a frontal assault – it was his style of fighting. To face Tarleton, he organized his troops into three lines. First, out front and hiding behind trees were selected sharpshooters. At the onset of battle they picked off numbers of Tarleton’s Dragoons, traditionally listed as fifteen24, shooting especially at officers, and warding off an attempt to gain initial supremacy. With the Dragoons in retreat, and their initial part completed, the sharpshooters retreated 150 yards or more back to join the second line, the militia commanded by Andrew Pickens. Morgan used the militia well, asking them to get off two volleys and promised their retreat to the third line made up of John Eager Howard’s25 Continentals, again close to 150 yards back. Some of the militia indeed got off two volleys as the British neared, but, as they retreated and reached supposed safety behind the Continental line, Tarleton sent his feared Dragoons after them.

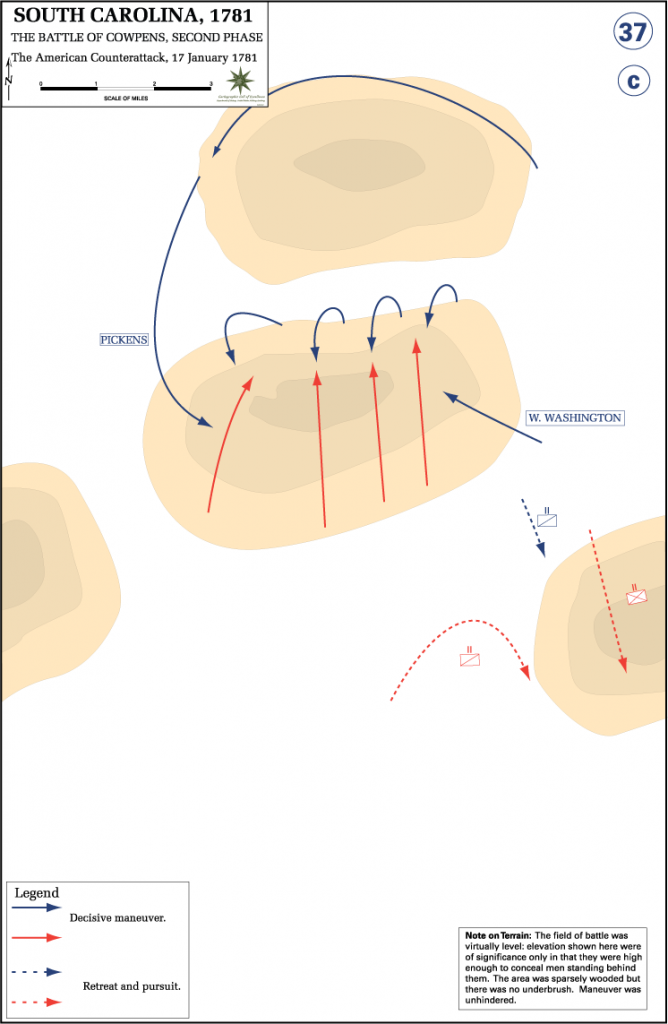

As the militia dodged behind trees and parried saber slashes with their rifles, William Washington’s26Patriot cavalry thundered onto the field of battle, seemingly, out of nowhere. The surprised British Dragoons, already scattered and sensing a rout, were overwhelmed, and according to historian Babits, lost eighteen men in the clash. As they fled the field, infantry on both sides fired volley after volley. The British advanced in a trot, with beating drums, the shrill sounds of fifes, and shouts of halloo. Morgan, in response, cheering his men on, said to give them the Indian halloo back. Riding to the front, he rallied the militia, crying out, “form, form, my brave fellows! Old Morgan was never beaten!”

Now Tarleton’s 71st Highlanders27, held in reserve, entered the charge toward the Continental line, the wild wail of bagpipes adding to the noise and confusion. A John Eager Howard order for the right flank to face slightly right to counter a charge from that direction, was, in the noise of battle, misunderstood as a call to retreat. As other companies along the line followed suite, Morgan rode up to ask Howard if he were beaten. As Howard pointed to the unbroken ranks and the orderly retreat and assured him they were not, Morgan spurred his horse on and ordered the retreating units to face about, and then, on order, fire in unison. The firing took a heavy toll on the British, who, by that time had sensed victory and had broken ranks in a wild charge. This event and a fierce Patriot bayonet charge in return broke the British charge and turned the tide of battle. The re-formed militia and cavalry re-entered the battle, leading to double envelopment28 of the British, perfectly timed. British infantry began surrendering en masse.

Tarleton and some of his army fought valiantly on; others refused his orders and fled the field. Finally, Tarleton, himself, saw the futility of continued battle, and with a handful of his men, fled from whence he came, down the Green River Road. In one of the most dramatic moments of the battle, William Washington, racing ahead of his cavalry, dueled hand-to-hand with Tarleton and two of his officers. Washington’s life was saved only when his young bugler29 fired his pistol at an Englishman with raised saber. Tarleton and his remaining forces galloped away to Cornwallis’ camp. Stragglers from the battle were overtaken, but Tarleton escaped to tell the awful news to Cornwallis.

The battle was over in less than an hour. It was a complete victory for the Patriot force. British losses were staggering: 110 dead, over 200 wounded and 500 captured. Morgan lost only 12 killed and 60 wounded, a count he received from those reporting directly to him.

Knowing Cornwallis would come after him, Morgan saw to it that the dead were buried – the legend says in wolf pits — and headed north with his army. Crossing the Broad at Island Ford30, he proceeded to Gilbert Town31, and, yet burdened as he was by the prisoners, pressed swiftly northeastward toward the Catawba River, and some amount of safety. The prisoners were taken via Salisbury32 on to Winchester, Virginia. Soon Morgan and Greene reunited and conferred, Morgan wanting to seek protection in the mountains and Greene wanting to march north to Virginia for supplies. Greene won the point, gently reminding Morgan that he was in command. Soon after Morgan retired from his duty because of ill health- rheumatism, and recurring bouts of malarial fever.

Now it was Greene and his army on the move north. Cornwallis, distressed by the news from Cowpens, and wondering aloud how such an inferior force could defeat Tarleton’s crack troops, indeed came after him. Now it was a race for the Dan River33 on the Virginia line, Cornwallis having burned his baggage34 and swiftly pursuing Greene. Cornwallis was subsequently delayed by Patriot units stationed at Catawba River35 crossings. Greene won the race, and, in doing so, believed he had Cornwallis where he wanted — far from urban supply centers and short of food. Returning to Guilford Courthouse36, he fought Cornwallis’ army employing with some success, Morgan’s tactics at Cowpens. At battle’s end, the British were technically the winners as Greene’s forces retreated. If it could be called a victory, it was a costly one: Five hundred British lay dead or wounded. When the news of the battle reached London, a member of the House of Commons said, “Another such victory would ruin the British army”. Perhaps the army was already ruined, and Greene’s strategy of attrition was working.

Soon, Greene’s strategy was evident: Cornwallis and his weary army gave up on the Carolinas and moved on to Virginia. On October 18, 1781, the British army surrendered at Yorktown. Cowpens, in its part in the Revolution, was a surprising victory and a turning point that changed the psychology of the entire war. Now, there was revenge – the Patriot rallying cry Tarleton’s Quarter 37. Morgan’s unorthodox but tactical masterpiece had indeed “spirited up the people”, not just those of the backcountry Carolinas, but those in all the colonies. In the process, he gave Tarleton and the British a “devil of a whipping”.

Cowpens was followed by a stand-off at Guilford Courthouse where, it is estimated, the British lost one-third of their force and some of their best officers. Siege of the British fort at Ninety Six put additional pressure on the British. Subsequent Cornwallis blunders and British failure to provide naval superiority led to his entrapment and Patriot victory at Yorktown. The blow was decisive; the war was lost, and American forces in the South played a great part in the final victory. Additionally, historians point to numerous militia skirmishes in the backcountry and to Greene’s long-term strategy of disrupting British logistics as crucial to final victory.

The Battle of Cowpens, in context of the Southern Campaign, was the turning point of the war in the South. Moreover, it contained the tactical masterpiece of the entire war—Morgan’s unique deployment of troops, including effective use of the militia and maximization of their strengths. Like Kings Mountain before, the victory at Cowpens was decisive and complete. But there was a difference: Kings Mountain had been an important victory over Tories; Cowpens was a victory over crack British regulars. Kings Mountain and Cowpens had both been political and psychological victories for the hearts and minds of the population, in effect blunting recruitment of Loyalists. The Cowpens victory also boosted northern morale, resulting in additional and greatly deserved military assistance for General Greene. These battles stopped a long string of retreats by American forces and initiated a chain of events leading to eventual Patriot victory at Yorktown. In truth, the Revolution was won in the South, and Cowpens played a major role in the victory.

–nps.gov