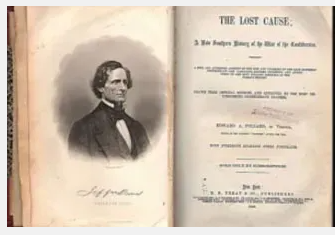

The Lost Cause by Edward Pollard is a seminal work in the development of a Southern White historical tradition recalling, celebrating, and interpreting the fallen Confederacy to those who were part of the four-year experiment and to their children and grandchildren. Published just a year after the end of the war, it was one of the first book-length works claiming to encompass the war’s full scope within its covers. Although I have seen the “Lost Cause” referred to in newspaper articles published before Pollard’s book came out, his The Lost Cause popularized the term and gave it widespread usage.

Let me begin by noting that the book The Lost Cause has some significant differences from the Lost Cause paradigm seen in later works. Pollard was writing the book in 1865 and 1866. He had not lived through Reconstruction, and Jeff Davis was not yet an unassailable martyr. Slavery was not considered irretrievably lost, and some Southerners thought that it could be restored. Although he popularized the term, Pollard died before anyone ever identified a “Lost Cause” school of history.

Pollard was a journalist, not a historian. He lived through the events he described, but he observed only a few of them first-hand. As the editor of the Richmond Examiner Pollard had a front row seat to the politics of the capital, but he is not to the military campaigns that fill most of the book. The Lost Cause lacks both the immediacy of a memoir and the temporal distance of a history. What it offers is a written attempt by a man on the losing side of a bloody revolt to come to terms with why the cause was worth sending young men to die for, and why it was lost.

Like other Lost Cause writers, Pollard depicts pre-war slavery as a benign institution benefiting both Southern whites and the United States as a whole. Unlike later Lost Cause writers, he clearly identifies Northern politics with the campaign to destroy slavery and the South’s secession with the need to wage war to preserve slavery.

Pollard wrote that the North believed that “slavery [was] the leading cause of the distinctive civilization of the South…and its superior refinements of scholarship and manners.” The North, he argued, was jealous of the civilization of the South and so “revenged itself on the cause, diverted its envy in an attack upon slavery, and defamed the institution as the relic of barbarism and the sum of all villainies.” He argued that while Northerners “defamed” the “institution of slavery, no man can write its history without recognizing contributions and naming prominent results beyond the domain of controversy. It bestowed on the world’s commerce in a half-century a single product whose annual value was two hundred millions of dollars. It founded a system of industry by which…capital…protected labour. It exhibited the picture of a land crowned with abundance, where starvation was unknown, where order was preserved by an unpaid police; and where many fertile regions accessible only to the labour of the African were brought into usefulness, and blessed the world with their productions.”

Pollard questioned the appropriateness of even using the term “slavery” to describe the ownership of Black humans by Southern whites. Pollard wrote that “we may suggest a doubt here whether that odious term ‘slavery,’ which has been so long imposed, by the exaggeration of Northern writers, upon the judgment and sympathies of the world, is properly applied to that system of servitude in the South which was really the mildest in the world; which did not rest on acts of debasement and disenfranchisement, but elevated the African, and was in the interest of human improvement…” The white man, he wrote, “protected the negro in life and limb, and in many personal rights, and, by the practice of the system, bestowed upon him a sum of individual indulgences, which made him altogether the most striking type in the world of cheerfulness and contentment.” Those who are opposed to slavery on moral grounds were “persons of disordered conscience,” argued Pollard.

Whatever cultural capital the Southern colonists brought with them to America, it was slavery which was the backbone of the distinctive society that they formed, said Pollard. He wrote that “Slavery established in the South a peculiar and noble type of civilization. It was not without attendant vices; but the virtues which followed in its train were numerous and peculiar, and asserted the general good effect of the institution on the ideas and manners of the South. If habits of command sometimes degenerated into cruelty and insolence; yet, in the greater number of instances, they inculcated notions of chivalry, polished the manners and produced many noble and generous virtues. If the relief of a large class of whites from the demands of physical labour gave occasion in some instances for idle and dissolute lives, yet at the same time it afforded opportunity for extraordinary culture, elevated the standards of scholarship in the South, enlarged and emancipated social intercourse, and established schools of individual refinement. The South had an element in its society — a landed gentry — which the North envied, and for which its substitute was a coarse ostentatious aristocracy that smelt of the trade, and that, however it cleansed itself and aped the elegance of the South, and packed its houses with fine furniture, could never entirely subdue a sneaking sense of its inferiority.”

Northern hatred of slavery took corporal form in the 1850s in the formation of the Republican Party. According to Pollard, the Republican Party was formed by the actions and money of the British abolitionists. Its members, he wrote, believed that “Slavery is a great moral, social, civil, and political evil, to be got rid of at the earliest practicable period.”

While later Lost Cause historians would claim that the Civil War war had nothing to do with slavery, Pollard saw it as central to the conflict. In this he reflected the views of Southern white leaders in 1860 and 1861-the earliest stages of the Secession Crisis. For example, Clement Claiborne Clay was one of the Southern senators who gave speeches in 1861 resigning from the U.S. Senate. Clay’s speech was delivered after his state, Alabama, had seceded from the United States.

In his speech, Clay said that Alabama had entered the Union at a time when the country was divided because of the North’s hostility “to the domestic slavery of the South.” He told his Senate audience that the years following Alabama’s admission were “strongly marked by proofs of the growth and power of that anti-slavery spirit of the Northern people which seeks the overthrow of that domestic institution of the South.… It is to-day the master spirit of the Northern States…”

Earlier, on January 7, 1861, Robert Toombs of Georgia delivered his speech explaining why he was leaving the Senate. His state had seceded, he told the Senate, because of the “success of the Abolitionists and their allies, under the name of the Republican Party…”

The earliest Lost Cause writers, like many of the 1861 Secessionists, were honest about the centrality of slavery to the Confederate cause. It was only later, when restoration of chattel slavery was recognized as impossible, that Lost Cause historiography obscured history and denied that the perpetuation of the enslavement of Black men, women, and children was the true Lost Cause of the Civil War.

–emergingcivilwar.com