When an enslaved man named Harry escaped from Mount Vernon in July 1771, his enslaver, George Washington, placed ads in newspapers seeking his capture. According to Washington’s cash accounts ledger, the war hero and then-delegate in the Virginia House of Burgesses paid a £1.16 reward (around $250 today) for the escapee’s prompt return to his Virginia estate. Harry’s attempt to gain his freedom was short-lived; at a time where there was little refuge for those who tried to flee from slavery, Washington’s reach proved inescapable.

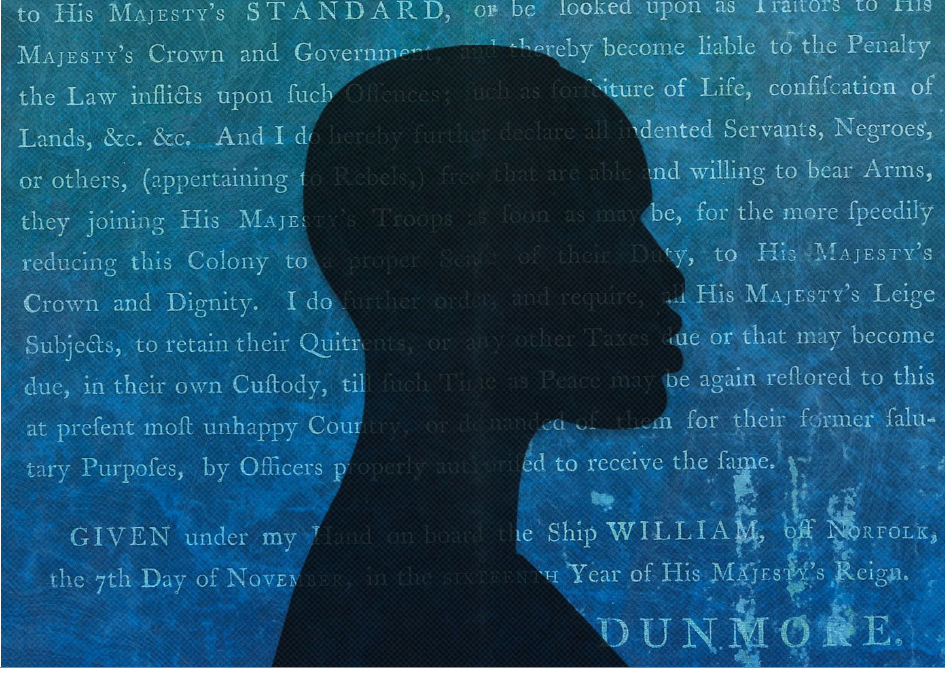

Four years later, however, an unexpected source presented Harry with another opportunity for self-emancipation. Six months after the “shot heard ’round the world” heralded the outbreak of war between rebellious colonists and British troops, Virginia’s last royal governor, John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore, lobbed a salvo of his own. In November 1775, Dunmore issued a proclamation from his headquarters-in-retreat—by then, a fleet of ships off of Norfolk. The notice called on “all [indentured] servants, Negroes or others (appertaining to Rebels), free that are able and willing to bear arms” to join George III’s army “as soon as may be.”

Harry took his chance, escaping once again in early 1776 and joining the roughly 20,000 self-emancipated people who fought for the British during the American Revolution. (An estimated 5,000 to 8,000 free and enslaved Black men fought for the Patriots’ cause.) Adopting the last name of his former enslaver, Harry spent the rest of his life pursuing the ideal for which the name Washington has long been revered in American history: fighting for freedom.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/a8/5fa89492-762c-42a6-a18b-18c809bdb0cd/george_washington_by_john_trumbull_1780.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/21/33/2133c5e1-348d-402b-81ca-c863b1415dc3/proclamation.jpg)

Colonial leaders were rightly afraid of Dunmore’s ploy, which was more strategic than benevolent. British representatives could set aside their own stances on slavery—Parliament didn’t outlaw the slave trade until 1807, and the practice persisted in British territories until 1838—and exploit the hypocrisy of rebellious, liberty-seeking colonists by playing to the hopes of those they enslaved.

But the move “backfired by uniting instead of intimidating the planter class—and [uniting] them against Dunmore,” says Alan Taylor, a historian at the University of Virginia and the author of American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. “Washington and [Thomas] Jefferson and others raged against Dunmore because they dreaded that he might succeed in rallying thousands of [enslaved people] against them.”

As James Madison wrote presciently in 1774, “If America and Britain should come to … hostile rupture, I am afraid an insurrection among the slaves may and will be promoted.” The future president cited a recent plot by some of “those unhappy wretches,” who had met in anticipation of the arrival of British troops. (Their plans were uncovered and quashed.) The enslaved people believed “that by revolting to [the British], they should be rewarded with their freedom,” Madison added.

Harry was one of more than a dozen enslaved people who fled Mount Vernon in response to Dunmore’s call to action. These individuals’ flight embodied a familiar sentiment. In 1774, with discontent fomenting in the Thirteen Colonies, Washington had expressed his fear that if the colonists didn’t assert their rights in the face of measures imposed by the British government, they’d be made into “tame and abject slaves, as the Blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.”

Infinitely less is known about Harry than the man who first purchased him before 1763. Born around 1740 in West Africa, Harry was among the estimated 12 million people kidnapped and sold into the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries. He survived the Middle Passage, a monthslong journey notorious for its crowded, unsanitary and cruel conditions, which were so horrific they killed an estimated 15 percent of those held in chains on slave ships.

After he was sold to Washington, Harry worked for the fittingly named Dismal Swamp Company, which counted his new enslaver as a major stakeholder. The business venture was a long-pursued, less-than-successful attempt to drain wetlands in Virginia and North Carolina, making the eponymous Great Dismal Swamp arable and, in turn, profitable.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8e/6a/8e6a236c-a78a-4568-84b7-a3019c45917d/junius_brutus_stearns_-_george_washington_as_farmer_at_mount_vernon.jpeg)

By 1766, Washington had transferred Harry to Mount Vernon, where he worked as a house servant and looked after the estate’s horses. In 1771, he was reassigned to one of Mount Vernon’s plantations. “For Harry to be moved from skilled work, which was in some measure self-directed, to grueling plantation labor must have dismayed him sufficiently to precipitate his flight” on July 29 of that year, wrote historian Cassandra Pybus in a 2009 essay collection. Returned to Mount Vernon after just a few weeks, Harry had to wait another five years for an opportunity to escape.

Soon after fighting began in April 1775, the Continental Congress named Washington commander of the new Continental Army. In November, around the same time Dunmore issued his proclamation, Washington banned free Black and enslaved people from joining the Continental Army. But he quickly saw the need to reverse course. Black soldiers went on to fight in many major battles of the war, including the 1781 Siege of Yorktown that dealt a crushing blow to British forces.

“The message Harry extracted from all this heady revolutionary tumult was that if King George III was now the master’s enemy, then it was to the king’s men that he would entrust his aspirations for freedom,” writes Pybus in Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty.

Washington saw Dunmore’s call to action as a clear threat to the Patriots’ incipient revolution. On December 26, 1775, he wrote that if Dunmore “is not crushed before spring, he will become the most formidable enemy America has.” The general added, “His strength will increase as a snowball by rolling; and faster, if some expedient cannot be hit upon to convince the slaves and servants of the impotency of his designs.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/07/9f/079fb4bc-8ff5-46b4-b6c3-a86b4df0a2be/screenshot_2023-06-13_at_103159_am.png)

Reaching Dunmore’s ships was a treacherous proposition for the enslaved people who got word of his offer. Those caught could expect to receive severe punishments reserved for fugitives; even individuals who evaded patrols and navigated their way to Dunmore’s fleet faced a reasonable chance of dying during a gruesome smallpox outbreak that was decimating the ranks of the British troops.

Still, fugitives from slavery flocked to Dunmore by the hundreds. While precise records of these self-emancipated people’s movements are elusive, Pybus suggests Harry was one of three enslaved men who arrived from Mount Vernon on a small boat at night and offered themselves up to the British in July 1776. Harry soon joined the Ethiopian Regiment, a group of formerly enslaved soldiers whose uniforms bore the inscription “Liberty to Slaves.” The regiment was later folded into the Black Pioneers, a noncombat unit tasked with building fortifications, supplying troops and other military engineering tasks. Harry attained the rank of corporal, serving in New York before accompanying British troops to Charleston, South Carolina.

In 1779, Henry Clinton, then commander of the British Army in North America, built on Dunmore’s words with the more sweeping Philipsburg Proclamation, which offered “to every Negro who shall desert the Rebel standard, full security to follow within these lines, any occupation which he shall think proper.” Clinton’s declaration added an estimated 100,000 fugitives from slavery, including families escaping together, to the British rolls. The 1780 capture of Charleston alone enabled thousands of enslaved people from nearby Southern plantations to join the British.

But the tide of war was not going in Britain’s favor, which portended danger to those who had sought freedom behind its army’s lines. In 1781, when British forces suffered an irretrievable defeat at Yorktown, General Charles Cornwallis retreated north—a decision that spelled doom for the self-emancipated soldiers he left behind.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/47/a3/47a38f38-d3aa-41ca-a92e-ef50b440c4d4/black-soldier.jpg)

Harry was fortunate enough to be in the British bastion in Charleston when Yorktown fell. But that luck wouldn’t hold for long. In December 1782, British forces completed their evacuation of Charleston, bringing Harry with them as they fled to the safety of the British Empire. The mass departure was a harbinger of the much larger evacuation from New York that took the place the following year.

Signed on September 3, 1783, the Treaty of Paris officially brought the American Revolution to a close, cementing the United States’ status as an independent nation. It stipulated that British troops should withdraw as soon as possible without “carrying away any Negroes or other property of the American inhabitants.”

To George Washington, this “property” included the enslaved people who had escaped from Mount Vernon to join the British, among them Harry and a group of men and women who sought refuge on the British warship the Savage in 1781. But Guy Carleton, Washington’s British counterpart, who took over from Clinton in 1782, interpreted the words differently.

A summary of the commanders’ exchange, recorded in the midst of negotiations on May 6, 1783, captures this sleight of hand: Washington “expressed his surprise” when informed that Carleton intended to include fugitives from slavery in the pending withdrawal, as they were not “property at the time,” having previously been freed by the British. Delivering these individuals up for severe punishment would be “a dishonorable violation of the public faith pledged to the Negroes,” Carleton argued.

Though no record remains of Harry’s thoughts on this turn of events, Boston King, who was born into slavery and joined the British in South Carolina, later wrote in his memoirs of the “inexpressible anguish and terror” brought on by the victors—escapees’ former enslavers—coming north and “seizing upon their slaves in the streets of New York, or even dragging them out of their beds.” The prospect of being enslaved and punished anew was unfathomable after several years behind British lines. “For some days, we lost our appetite for food, and sleep departed from our eyes,” King wrote.

The stakes were high for all—and Harry had escaped from none other than the commander in chief of the now-victorious Continental Army.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/38/1f38a536-9cef-4d4e-9651-fa8dbd6f1b63/washingtons_entry_into_new_york_on_the_evacuation_of_the_city_by_the_british_nov_25th_1783_lccn2002698178.jpg)

Avoiding severe punishment or death at the hands of the Americans was no guarantee of an easy fate for the 8,000 to 10,000 formerly enslaved people “who survived to evacuate [to] freedom with the British,” writes historian Maya Jasanoff in Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World. Mixed in with a large influx of white settlers in Nova Scotia, self-emancipated individuals had a particularly difficult time obtaining plots of land or earning wages in line with those of their white counterparts.

Resettlement proved difficult in Britain and other imperial territories, too. In the streets of London, many formerly enslaved Loyalists lived in unrelenting poverty. The white abolitionist Granville Sharp launched the Sierra Leone Company, a corporation that aimed to resettle free Black people in Africa, in 1791 in response to the dire conditions he witnessed in England’s capital. Sharp and the company’s other stakeholders saw relocation, not integration, as the best solution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/8c/918c4cbb-4ed6-4cd2-a788-2b1b3042199f/wash.jpg)

A 1791 Sierra Leone Company advertisement offering a minimum of 20 acres per person—and more for men with families—readily appealed to Nova Scotia’s disillusioned Black settlers. It also raised the specter of ever-elusive equal rights, promising that “the civil, military, personal and commercial rights and duties of Blacks and whites shall be the same and secured in the same manner.”

Sharp had struck a deal with a local leader for land in Sierra Leone. Despite the failure of an earlier settlement attempt that was torpedoed by bad weather, sickness and a less welcoming attitude on the part of other local leaders, the abolitionist’s vision endured and was on offer once again in 1791. About 1,200 formerly enslaved people, including Harry, set sail across the Atlantic in 1792—this time eastward and of their own volition—in hopes of being dealt a better hand.

Freetown, as the new colony was called, didn’t evolve into the egalitarian, self-governing ideal Sharp had envisioned. The Sierra Leone Company took control of the enterprise under the auspices of the British government. In some ways, Freetown’s trajectory paralleled that of the American colonies, as a series of governors imposed increasingly stringent measures to force the settlers into line. During the remainder of the 1790s, myriad problems beset the venture, from infighting with locals to financial nonviability. Officials turned to unfavorable land relocation and quit-rent, a holdover from feudalism that was essentially a land tax, in hopes of course-correcting.

In 1800, Harry, by then around 60 years old and one of Freetown’s more successful farmers, was arrested and tried with approximately two dozen others after participating in a meeting of settlers lobbying for the modicum of self-determination they had been promised. Unlike some of the other defendants, he was not sentenced to death but instead banished across the Sierra Leone River. What scant records of his life survive today fail to illuminate its closing chapter.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d0/c8/d0c8f83b-d2e0-4a74-9b3c-0d555048a0f2/screen-shot-2020-03-19-at-31655-pm.png)

Harry’s banishment was the culmination of four decades spent seeking the freedom taken from him when he was a young man. The thousands who pursued the same bold course of joining British forces defy tidy narratives about the Revolutionary War and the liberation for which the colonists fought.

Loyalist refugees like Harry were bound up in contradictions, Jasanoff argues:

They were provincial settlers who became international migrants. They were British subjects who proved their loyalty in one setting and resisted imperial authority in others. They were Americans who failed or refused to find a place in the republic. They were refugees who never became stateless persons in the modern sense. And they were exiles who could go home again, thanks to [post-War of 1812] reconciliation, by later returning to the United States.

Shortly before Dunmore issued his proclamation in 1775, Lund Washington, the overseer at Mount Vernon, wrote to his cousin George to express concern that “there is not a man of them but would leave us if they believed they could make their escape.” The reason, he noted, is one that compelled many enslaved people to seek that most basic of human needs and risk everything in its pursuit: “Liberty is sweet.”

–smithsonianmag.com