The N.C. History Center on the Civil War, Emancipation & Reconstruction will use local stories to tell “the truth with all its blemishes”—even if it upsets some people.

During the Civil War, North Carolina contributed more soldiers to the Confederate cause than any other state.

North Carolina was also the next-to-last state to secede, and it was home to pro-Union movements that persisted throughout the war.

Those are all facts, and they’re part of the complex history the state is taking on in building the $87 million N.C. History Center on the Civil War, Emancipation & Reconstruction. Organizers say the Fayetteville museum, which has been two decades in the making, will help North Carolina’s educators teach a nuanced, factual story as unresolved racial and political divisions continue to cleave the country.

One thing the museum’s backers are clear on: That story is about more than a war. It’s a long, dark period in the state’s and nation’s history, not a Lost Cause. The history center’s job is to “right the historical understanding” of events between 1838 and 1898, according to Michael McElreath, the center’s education initiatives director.

“The perspective that the war was really about arcane issues of constitutional balancing between the states and the federal government—that’s just not an acceptable perspective, given all that we’ve now learned,” he said.

Or, as the subject line of a February 2024 History Center email to reporters put it: “The Civil War WAS about slavery.”

North Carolinians, it seems, are still divided on the war’s causes. In a 2021 poll of North Carolinians by Elon University, 51 percent of respondents said they believed the Civil War was “mainly about” states rights; 49 percent said it was mainly fought over slavery.

It will be two years before the museum opens. But teachers around the state are getting a first look at the museum’s approach now in a series of two-day symposiums that bring together K-12 educators with scholars to learn about local Civil War history.

At one of these symposiums in October, 20 teachers from Mecklenburg, Cabarrus, Gaston, and Lincoln counties gathered in Charlotte to tour a plantation and hear from experts about the war and post-war Reconstruction period in the Piedmont. Barton Myers, professor of history at Washington and Lee University, talked to the teachers about persistent pro-Union sentiment in Guilford and Randolph counties, spurred by the Confederacy’s introduction of a draft in 1862.

“That took the power of the state and military right to the door of people who may never have been involved with the Civil War at all,” Myers said.

That led the group to discuss the experience of Stephanie Whitehead. A pro-Union slaveholder in Pitt County, she attempted to pay her sons’ way out of the war with money and enslaved people. One son still got drafted and was killed in action. At one point, Myers said, Whitehead threatened to shoot Confederate soldiers who came to her plantation seeking food. Teachers debated whether Whitehead was truly anti-Confederacy or “just anti-my-son-going to war.” The focus on individual North Carolinians, in all their complexities, revealed truths the group hadn’t encountered before.

“A lot of this is stealth history,” said Bobby Harley, a teacher at Warlick Academy in Gastonia.

The Stories We Tell

A nuanced look at history like that is difficult to bring into the classroom, given the time constraints and sensitivities N.C. teachers face, said McElreath, who is also the experiential learning director at Cary Academy, a private school that teaches grades 6-12.

North Carolina public school students study the Civil War and Reconstruction three times: in the fourth, eighth, and 11th grades. The state sets broad standards for what students should learn across the social studies curriculum in those grades. Eighth-graders should “understand the role of conflict and cooperation in the development of North Carolina and the nation,” according to one of the seven standards for that grade.

How that understanding gets built is largely up to local school districts and teachers, said Tom Daugherty, a K-12 social studies education consultant at the N.C. Department of Public Instruction.

A state textbook committee has approved social studies textbooks for each of those grade levels. But, Daugherty said, most districts choose not to use them because there’s no mandated end-of-course test to teach toward and there are so many materials available online. That means there’s not much consistency in how it’s taught outside of Advanced Placement courses. Instead, districts tap groups of teachers to write curricula, and the educators themselves largely choose the materials.

Other states are more prescriptive about how the Civil War is taught. Standards in eight of the 11 former Confederate states identify slavery as one of several causes of the war, alongside states’ rights, sectionalism, and, in some cases, differences over the role of Congress. A 2023 rewrite of Florida’s social studies standards identifies slavery as one of several causes of the war. It also directs middle school teachers to cover “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Teaching the truth about the Civil War and Reconstruction matters, McElreath said, because so many of the problems that went unresolved in the 1860s and 1870s still plague America today. In the 2021 Elon University poll, nearly two-thirds of respondents said they believe slavery still affects the status of Black Americans either “a great deal” or “a fair amount.”

To McElreath, images of people carrying a Confederate flag as they stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, are evidence enough of the Civil War era’s ongoing relevance.

“That memory has been used as a cudgel to keep certain people down,” he said. “All of the really, really complex interplays between that history and memory deserve more space than we typically have time to give them. That’s the hardest thing about teaching this.”

The teachers at the symposium agreed that the time crunch is a challenge for them, particularly at the high school level. In 2019, the General Assembly passed a law adding personal finance and civic literacy classes to social studies requirements. To accommodate them, American history was condensed from a yearlong course into a single semester.

“It’s easy to paint in broad brush strokes, especially with the time we have,” said Cale Thornburg, an East Lincoln High School history teacher who participated in the October symposium sponsored by the history center.

“If we got the best minds in the state and told the truth with all its blemishes…that may upset people.”Mac Healy, co-chair of the Fayetteville history center’s board of directors

Symposium participants also cited a dearth of materials on local events and the challenges of taking on the volatile subject matter, given the strong opinions students may bring and the developmental stages that teenagers go through, particularly in the eighth grade.

“We’re covering 50 years of history in about four weeks,” said Mike Savoia, a third-year teacher at Parkway Middle School in Monroe. “The depth of information and the images—13- and 14-year-olds don’t always understand how to fully take that in and use it for good.”

McElreath’s symposiums aim to arm teachers with primary source materials that tell local and state stories. Focusing on local history and the people who experienced it “is a powerful tool for engaging students and their families,” according to the American Historical Association’s Criteria for Standards in History.

“Having more specifics from here makes it easier for the kids to understand,” Savoia said. “When they go out in this city, they can see that something happened right over there, instead of in California or New York or Florida.”

Beyond new tools, the symposiums give educators a forum for talking honestly together about the challenges of teaching painful, politically fraught history. “Get comfortable being uncomfortable” is a mantra McElreath repeats throughout the two days. That’s something the teachers steeled themselves to do at the close of the event. When the college scholars departed, chairs that had faced a lectern were moved into a circle so the educators could speak and listen to one another.

“What’s salient to you from the last two days?” McElreath asked them.

“What I want to focus on from this is origins,” said Jocelyn Roundtree, a social studies teacher at Olympic High School in Charlotte. “We spend so much time in the classroom doing and making things without knowing why we do them. It’s important for students to grasp the ‘why’ behind the ‘what.’”

Harley and Imani Rankin discussed how the Civil War and Reconstruction echo in their own professional and educational histories. Harley was a teacher at Charlotte’s Julius Chambers High School in 2021 when it was renamed from Zebulon Vance High School. Vance, a slaveholder, was governor of North Carolina for most of the Civil War. Chambers founded the first integrated law firm in North Carolina in the 1960s and was a longtime civil rights attorney.

“I think of HBCUs,” said Rankin, who graduated from North Carolina A&T, a historically Black university. “Something beautiful did come out of Reconstruction.”

Several of the teachers referenced letters and other primary source documents as tangible ways they’d carry the symposium with them.

“Having these primary sources and documents will give us the courage and the confidence to talk about this with our students,” Harley said.

An Opportunity and an Odyssey

The start of construction on the main building of the N.C. History Center on the Civil War, Emancipation & Reconstruction in mid-2025 will mark the final chapter of a somewhat uncomfortable two-decade effort to bring a Civil War museum to Fayetteville.

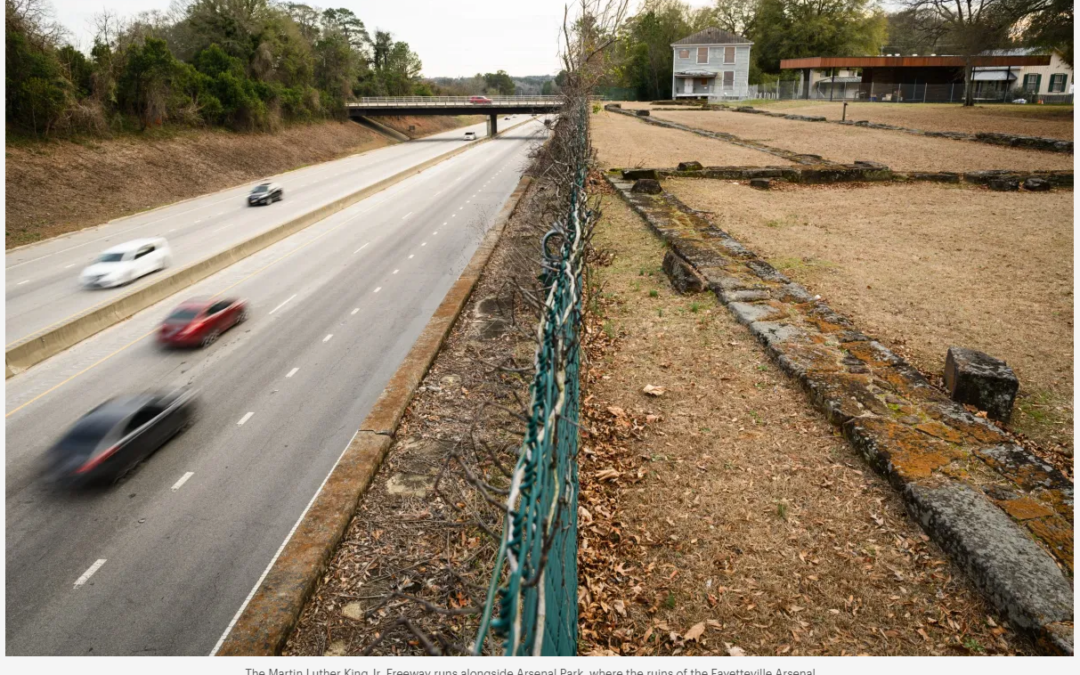

That odyssey began in the early 2000s, when a group of local museum backers began looking for a way to make the Museum of the Cape Fear, a state-run facility focused on the history of the 20-county region around Fayetteville, more relevant. A consultant suggested the answer was in the ground beneath the existing museum. That plot of land, on a hill overlooking downtown Fayetteville, had been home to a federal arsenal that passed through Confederate and Union control during the Civil War. Mac Healy, a local businessman who co-chairs the museum’s board of directors, said the group saw possibilities and peril in the idea of expanding the existing museum and refocusing it on the Civil War.

“If we got the best minds in the state and told the truth with all its blemishes, this would be a world-class center,” he said. “That may upset people.”

And it did.

Resistance came from City Council members concerned the museum would hallow the Confederate cause, Healy said. Members of the council balked at the center’s original name, the North Carolina Civil War History Center. Backers eventually changed it to address concerns that the museum would focus too squarely on the Confederate era. The name change helped secure $6.6 million from the city.

The group also drew complaints from members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans unhappy that the new history center wouldn’t fly the Confederate flag, according to David Winslow, a consultant who helped develop the museum’s concept and raised funds for it. (The group didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

“Having these primary sources and documents will give us the courage and the confidence to talk about this with our students.”Bobby Harley, teacher at Warlick Academy in Gastonia

As Healy, Winslow, and museum co-chair Mary Lynn Bryan worked to address objections and raise money, the task of commemorating Civil War history became far more fraught. A wave of protests between 2015 and 2020 led to the removal or renaming of Confederate monuments throughout the South. In North Carolina alone, 23 monuments came down in 2020, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Fayetteville felt that upheaval acutely. During a May 2020 protest after the murder of Fayetteville native George Floyd in Minneapolis, two men set fire to the Market House, a historic downtown building that was a center of trade, including the sale of enslaved people, in the mid-19th century.

In 2022, Congress announced that Fort Bragg, the massive U.S. Army base named for Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg, would be renamed Fort Liberty. In February 2025, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced the base would once again be named Fort Bragg, this time in honor of Roland L. Bragg, a U.S. Army private who won a Silver Star in World War II.

The unrest wound up helping the group secure state funding for the new museum. John Szoka, a Fayetteville Republican who chaired the N.C. House Finance Committee from 2015 to 2022, said he was disturbed by Floyd’s murder and saw the planned N.C. History Center as “something tangible that helps us heal.”

Szoka helped Healy and other museum boosters make their case directly to legislators. When necessary, he also used his power as a longtime finance chair to wrangle colleagues. The state allocated $59.6 million to the project in 2021 and another $10 million in subsequent budgets. That money joins the funds from the city, $7.5 million from Cumberland County, and $15 million from private backers.

“I had some juice in the legislature,” said Szoka, who retired from the House in 2022. “When I said it was a good thing, people trusted me.”

For museum organizers, the post-Floyd upheaval “made us more relevant,” Winslow said. “It was even more important that we do this and do it right.”

Doing it right, to the museum’s organizers, means telling a fact-based story that elevates the experiences of enslaved people, women, Black laborers and Native Americans who aided the Confederacy, and North Carolina Unionists.

“Learning these stories makes us all wiser and more empathetic to the lessons the history can offer to us and, even more importantly, how the knowledge that they offer can help make us more empathetic towards one another,” said Spencer Crew, former director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, at the June 2022 groundbreaking for the new museum. Crew is one of several contributing scholars who’ve helped write the story the history center will tell.

The museum’s exhibits will cover an era beginning in 1838 and ending in 1898, when the Wilmington massacre effectively ended an era in which Black people shared political power in North Carolina. When it opens in 2027, the physical facility will include a state-of-the-art, 65,000-square-foot museum and several historic buildings that have already been moved to the site. Private collectors in 2019 donated a $6.5 million cyclorama painting of the Battle of Gettysburg, but it won’t be on display when the center opens.

There will also be a digital educational component that includes more course materials for teachers and stories sourced from all 100 N.C. counties.

And the history center will become part of the network of museums owned and administered by the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, fulfilling a goal Healy set when planning began 20 years ago.

“When my kids wanted to study the state of North Carolina, they got on a bus and went to the zoo or something,” he said. “I’m ready for people to get on a bus and come to Fayetteville to learn about the state of North Carolina.”

–theassemblync.com