In 1896, Francis Marion Boyer, fleeing threats of racial violence, traveled more than 1,200 miles from his home in southwest Georgia to New Mexico. The educator and graduate of what is now Morehouse College thought life on the Great Plains could offer the land ownership, opportunity and freedom he couldn’t find in his home state.

By 1903, he and 12 other Black settlers had founded Blackdom, New Mexico, just 15 miles south of Roswell, with $10,000 in combined assets. The town would grow into a village with a post office, store and church before poor irrigation and low crop prices put the farms out of business. By the late 1920s, Blackdom was gone. Today it is only identifiable by a historic marker placed on U.S. 285.

Boyer was one of 1.6 million homesteaders to claim land in what has been called the federal government’s biggest wealth distribution program — the promise of free land to anyone with enough grit and determination to make it their own. Thousands of homesteaders were Black people like Boyer who only at the end of the Civil War gained the legal right to chase their American dreams. For many years, their stories were largely untold.

“Homesteading is a great American story and I am excited that it is a more diverse story than the traditional history has been,” said Richard Edwards, director of Black Homesteaders in the Great Plains, a project partially funded by the National Park Service to preserve the history of six major Black homestead communities.

Like many other settlements in the American West, Black homestead colonies, stretching from South Dakota to New Mexico, would become casualties of dust storms and a failing national economy, but descendants of Black homesteaders have fought to preserve the memory of their ancestors through historical markers, annual homecomings and cultural exhibitions.

In a 21st-century twist, 19 Georgia families have drawn inspiration from homesteaders’ dreams of self-sufficiency, prosperity and opportunity to establish the Black town of “Freedom” on 500 acres of land near Macon.

“The idea of building an intentional community with our friend group has been around in our circle for some time,” said Ashley Scott, vice president and co-founder of the Freedom Georgia Initiative. “It is about generational wealth for us. To have a sense of security as a people, our best investment is the land.”

‘The big push was Jim Crow’

In 1862, the Homestead Act made land ownership a reality for almost anyone. While previous statutes that transferred public lands to private citizens relied on cash payments or credit, the Homestead Act allowed citizens or those intending to become citizens to earn 160 acres of land by paying nominal fees and agreeing to build and farm on the land for five years.

For Black Americans, there was one problem — they didn’t qualify as citizens until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Reconstruction-era policies designed to address inequities of slavery had brought political, social and economic advancement to formerly enslaved people, but as government oversight gave way to a system of legal segregation known as Jim Crow, the climate for Black Americans changed.

When an extension of the Homestead Act, the Southern Homestead Act of 1866, failed to redistribute land to newly free Black citizens as intended — most of the 3 million acres of land in Southern states that was distributed went to white people — many Black people decided they might have better outcomes in the West.

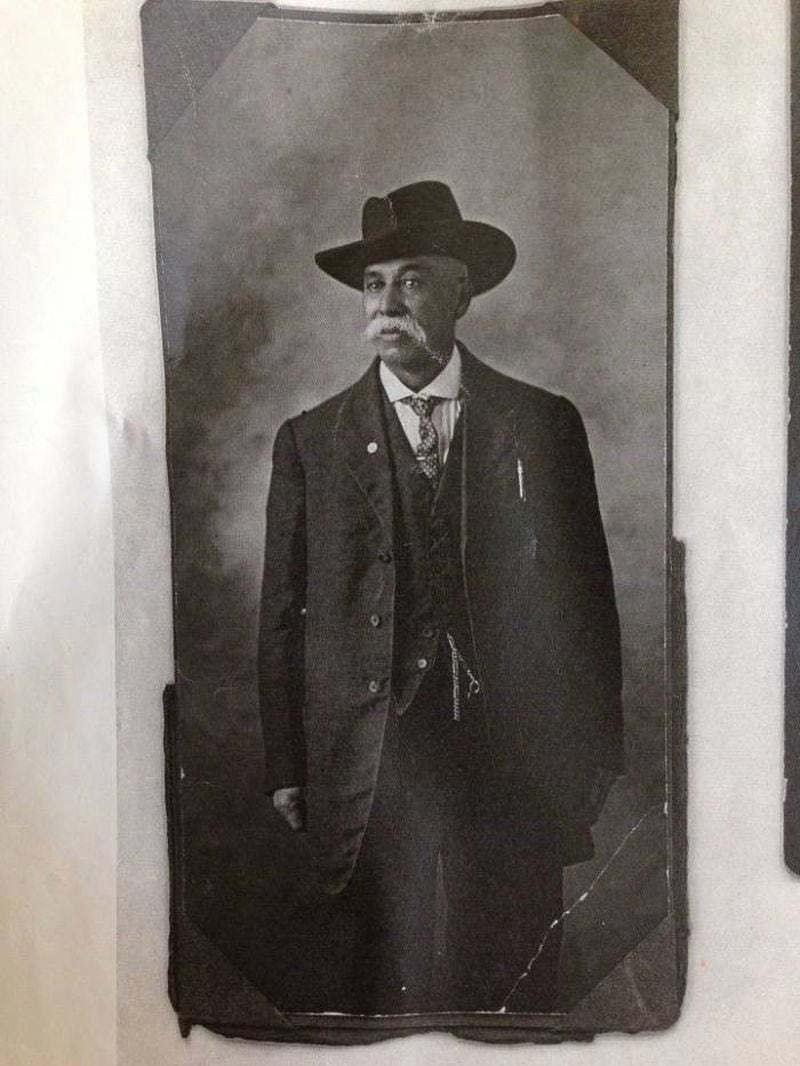

Credit: Courtesy of Charles Nuckolls

“(Freed Black people) became homeless basically, so homesteading in the West becomes the big draw and the big push was Jim Crow,” said Angela Bates, founder of the Nicodemus Historical Society and Museum. Bates’ great-great-grandfather was one of the first Black settlers to arrive in Nicodemus, Kansas, in 1877.

With about 22 residents, Nicodemus is the only Black homestead colony that is still inhabited. Bates, 68, grew up in California, but each summer her family packed up the station wagon and hit Route 66 to visit relatives in Nicodemus and enjoy the annual Emancipation Day homecoming on Aug. 1.

In the 1990s, Bates moved to Kansas and made it her mission to preserve the town of her ancestors. She set up an archive at the University of Kansas, and after years of campaigning, she succeeded in getting designations as a National Historic Site of the National Park Service and the National Register of Historic Places.

At its peak in the 1880s, Nicodemus had more than 300 residents, along with a store, hotel, churches and a post office. A partnership between Black entrepreneurs and a white developer helped the town recruit hundreds of Black migrants from Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi.

But the biggest boost, and what may have helped Nicodemus survive the challenges that leveled other Black homestead colonies, said Bates, was two well-educated Chicago transplants who helped organize Nicodemus as a township, giving them a political and economic stake in the county.

“I have always thought Nicodemus would become a beacon of hope for African Americans in the U.S., an example of what African Americans can do for themselves,” said Bates.

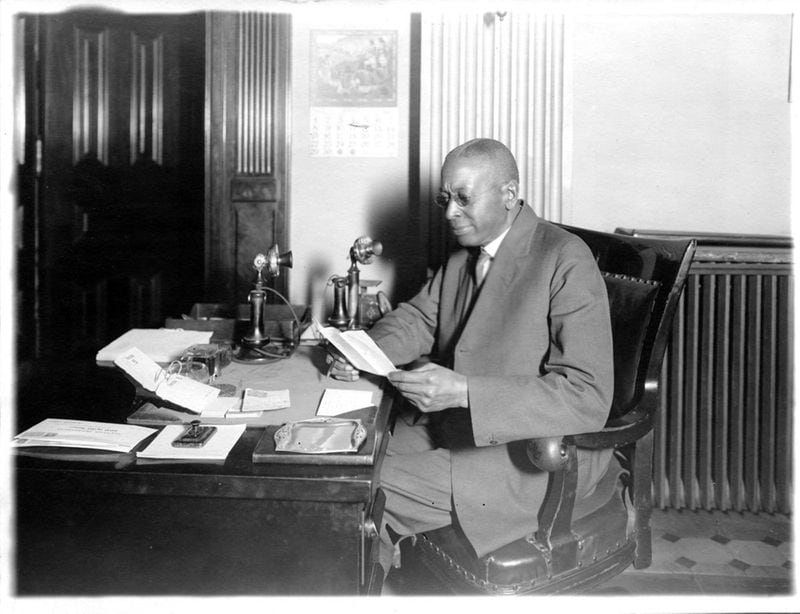

Credit: Library of Congress

Discovering ties to history

Even in the early 1900s, Black homestead colonies seemed to draw inspiration from one another.

One group of Black homesteaders left Nebraska to set up a colony in Empire, Wyoming, under the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909, which allowed applicants to claim 320 acres of land.

Though Empire experienced moderate prosperity, dryland farming was challenging and the farms had no access to irrigation. Still, residents persisted until an incident with racial overtones tore the town apart, said Edwards. Russell Taylor, a town leader, was grief-stricken when his mentally ill brother was killed by sheriff’s deputies in 1913. The incident would linger over the town and hasten its decline, said Edwards.

Some Empire residents returned to DeWitty, a colony in Nebraska that blossomed in 1904 with the Kinkaid Act, which allowed homesteaders to claim 640 acres of land in the sand hills.

Artes Johnson remembers the stories his grandmother would tell as they sat around the television on Sundays watching “Wagon Train.”

“We said, ‘Grandma, you were in a wagon like that and you rode horses?” said Johnson, 70, of Omaha. “We sat there in disbelief, but when the commercials were over, we just said, OK and went back to watching the show.”

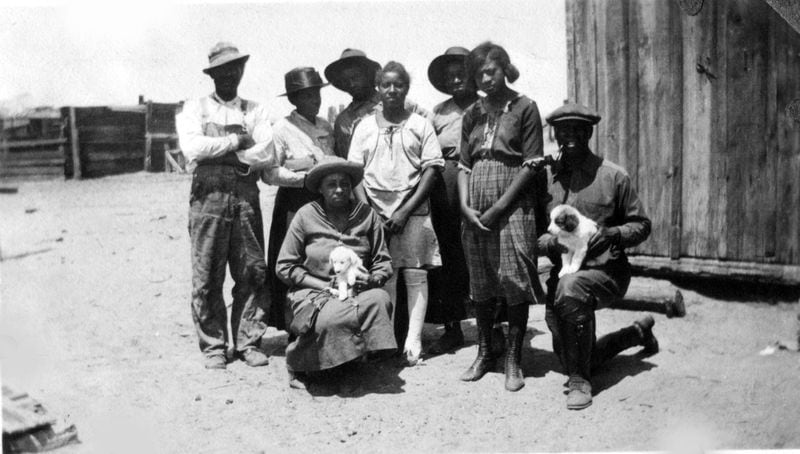

Johnson, whose great-great-grandfather William Parker Walker, a Black Canadian, was among the first Black settlers in Nebraska in the late 1800s, founded the Descendants of DeWitty. Members have helped create a traveling photo exhibition, educational presentations and reenactments of DeWitty settlers.

Credit: Artes Johnson

When the Nebraska State Historical Society installed a historic marker in 2016, it introduced Delbert DeWitty to family history he knew nothing about. Through Descendants of DeWitty, he learned that Miles DeWitty, the Nebraska homestead’s namesake who ran the post office and a small store, was his great-uncle.

“I wondered how many African Americans are just like me and still don’t know,” said DeWitty, 69, of Atlanta. “There are probably thousands of examples like that. We didn’t do a lot of documenting of our history.”

Building a legacy: Progress vs. risks

For DeWitty settlers, education was a primary goal, DeWitty said, and the colony established several school districts when the population was at its peak. Though Black homesteaders viewed education as one of the marks of being truly free and equal citizens, it came with some risks, Edwards said.

“How do you keep your kids on the farm when you have educated them to be an engineer? There was a process in the colonies that resulted in their own demise,” said Edwards.

In addition, Black colonies were generally isolated, sandwiched between larger white towns. Young people seeking mates had to leave town to avoid dating a relative, Edwards said.

The exodus of young people along with the severe drought of the Dust Bowl and limited economic resources during the Great Depression devastated many Black homestead colonies, even those that had successfully operated for 20 to 25 years. Only now are the populations of many communities in the West returning to levels not seen since 1910, Edwards said.

“Part of this story as traditionally told is these were ephemeral communities that were failures. That is a total misread of what these people were about and what they were trying to achieve,” Edwards said. “They wanted to create a legacy, but they wanted a legacy that would help them move ahead.”

Some Black homesteaders were advocates of racial integration for whom success meant finding a place in the white economic power structure.

Credit: Courtesy of Charles Nuckolls

Oliver Toussaint Jackson, who worked as a messenger for the governor of Colorado, proposed the idea of a Black colony to the governor. In 1911, Dearfield was established by seven Black families with a lot of enthusiasm and little farming experience.

Among their ranks were prominent members of Denver’s Black society who came for political and cultural reasons rather than economic need, said Charles Nuckolls, a filmmaker of the 2019 documentary “Remnants of a Dream: The Story of Dearfield Colorado.”

“They believed in the movement and they wanted it to succeed. They purchased homesteads as an investment, but they were doing it to support the cause of self-sufficiency,” Nuckolls said.

Jackson, he said, was a visionary who was not just developing the town of Dearfield but was also advocating for workers’ rights in state government, leading voter registration drives in the 1920s and trying to impress on Black Americans the importance of taking part in the election process.

Credit: Courtesy of Charles Nuckolls

“You can draw a direct line between where people are today and the efforts of people like O.T. Jackson in politics and civil rights,” Nuckolls said. “The homestead didn’t last but I would invite people to look at this from a different perspective … not whether homesteads of the past were successful or not … (but) what is homesteading in 2021?”

For the Freedom Georgia Initiative, the answer lies in hundreds of acres of red dirt and bare land located two hours southeast of Atlanta. Freedom, they said, will be a place for Black people who seek prosperity, a connection to the land and a lived experience of healing and wellness.

“Our whole community design is wrapped around wellness and healthy living where you can live at a level of prosperity and innovation and where abundance and culture can thrive,” said Scott.

With plans to meet the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations — which include eliminating poverty and hunger, reducing inequality and building sustainable communities — their first big project is a farming initiative. They plan to begin building homes once a master plan is in place and they have secured funding, Scott said.

Since announcing their plans last year, 1,300 individuals from as far as Sierra Leone have joined the movement to live in Freedom or provide financial support for the town development. The founding families meet weekly to discuss important developments and build the bonds that will help them grow together as a community.

“Anyone who understands anything about wealth generation understands that it starts with land,” said Scott. “Our goal is to build a community that is so successful that (our children) don’t have to go looking to anyone else’s system for success. We will have created an empire that they inherit and that they own.”

–ajc.com