When I recently visited Montgomery, Alabama, I went to see the rows of rusted plinths that together make up the city’s Peace and Justice Memorial. The memorial is designed to replicate the cycle of a lynching. Walking through the memorial, one will see plinths hanging from the ceiling, and others rising out of the ground like coffins. Each plinth represents a county, inscribed with the names of thousands of Black Americans who had been lynched by their neighbors and fellow citizens, and the date of their murders. Less than a half mile away, just outside the state capitol building, stands a statue of Jefferson Davis, and a gigantic Confederate monument. It’s a jarring reminder that while the Union won the American Civil War, formally ended chattel slavery, and forced compliance with federal law, we continue to live with the legacy of losing the civil war peace.

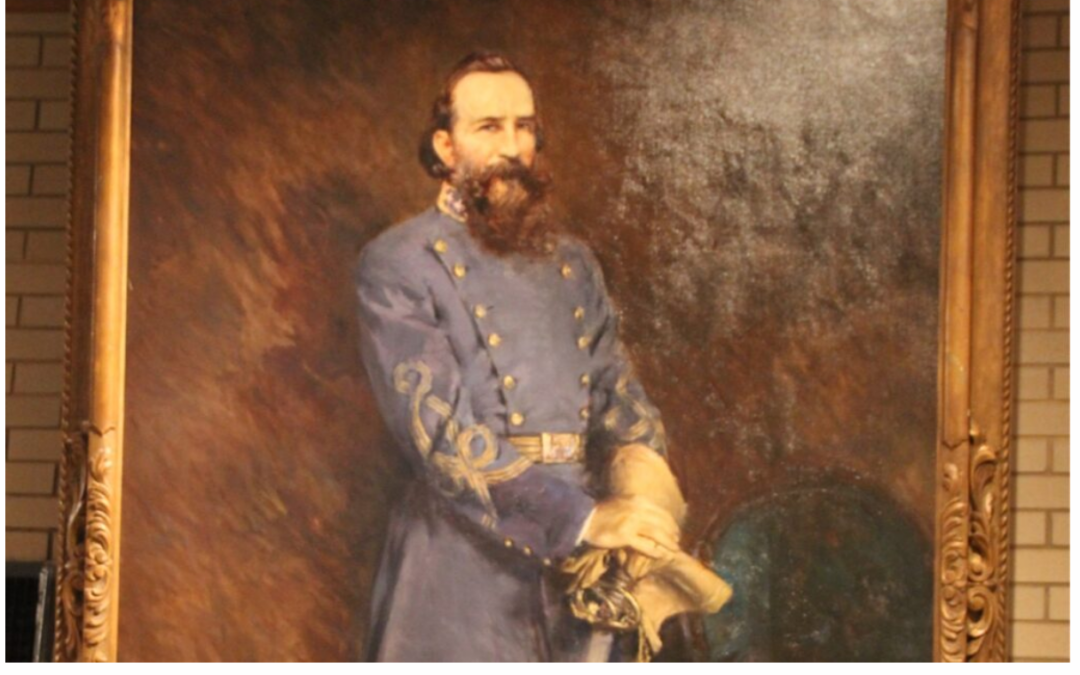

That legacy is not just evident in the culture of the American south, but also in the U.S. military. When the armed services inventoried their real property holdings at the request of the Naming Commission, on which I served, they identified more than 10,000 installations, streets, apartment buildings, swimming pools, and other properties commemorating people who voluntarily took up arms against the U.S. government. Beginning in 1952, the U.S. Military Academy proudly displayed in its student library a 20-foot-high painting of Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general and former superintendent of the academy. It depicts Lee wearing his Confederate uniform in the foreground with a black slave in the background holding his horse. The painting had been given to the academy by the Daughters of the Confederacy as the cases that would become Brown vs. Board of Education were percolating through the courts. Arlington National Cemetery, which only permitted Confederate soldiers to be buried there starting in 1898, had a 40-foot high Confederate memorial including friezes of faithful black slaves serving their white masters — it was only removed in December of 2023.

Within the military, far and away the greatest influence of the lost cause of the Confederacy is in the Army: 10 major Army posts were named for Confederates, two Navy ships, and essentially nothing in either the Marine Corps or the Air Force. The veneration of Confederate military leaders by the Army has partly to do with the legacy of so many West Point graduates choosing to serve the southern cause during the war (including Lee), partly to do with efforts to bind the nation back together after the war, but also much to do with resurgent socio-economic and -political practices in the south. Military bases were named to please the communities in which they were situated, and they were created as the military expanded during the Jim Crow years of the early 20th century.

None of those bases — or anything else — were named for Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, although he was Lee’s most trusted lieutenant. But Longstreet was also the only major Confederate figure who participated in enforcing the political settlement the Union imposed on the secessionist states. While a slaveholder, racist, and traitor to the Union, he nonetheless believed that having lost the war, the seceded states had a responsibility to uphold the terms of surrender and accept the consequences of unsuccessful rebellion: abolition of slavery, adherence to the laws of the United States, and military occupation until determined by the victorious power to be rehabilitated and re-admitted to national political participation.

For these views and acts, Longstreet was termed by his southern brethren as “Lee’s tarnished Lieutenant.” Not only has his post-war record been vilified by his confederates, but his counsel to Lee and battlefield leadership are also hotly contested. In her book Longstreet: The Confederate General Who Defied the South, Elizabeth Varon has undertaken an incredibly important historical task, which is to excavate Longstreet from the “lost cause” mythology that emerged as the Confederacy that lost the war won the peace.

The military historian Peter Cozzens reviewed this book in the Wall Street Journal, negatively and I think unfairly. Cozzens’ main complaint about the book is that it focuses too little on Longstreet’s Civil War record, when Varon’s subject is the way his post-war choices have colored southern historiography of his record. She is writing a life, not a war. Cozzens was complaining that she didn’t write the book he wanted her to write, not evaluating the book she has written.

And the book she has written is incredibly important. What Varon shows is the politicization of history to exculpate the moral bankruptcy of southern social, economic, and political practices. Her careful scholarship demonstrates that Longstreet differed with Lee over strategy, but properly deferred to his commander — and that criticism of his wartime performance begins in earnest only after the war, when his post-war political choices affronted the emergent storyline of the defeated Confederacy.

That storyline, known as the “lost cause,” seeks to repudiate the Union victory, or disparage it as the product solely of superior resources in the hands of incompetent Union generals. The purpose of the lost cause myth was more than salving the wounded pride of defeated southerners, though. As Varon writes, “by denying the legitimacy of the North’s military victory, former Confederates hoped to deny the North the right to impose its political will on the South.”

Southerners were aided in this purpose by the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. As Varon and every other historian of the era show, “[President Andrew] Johnson’s policies permitted former Confederate leaders to return to power in the south and emboldened them to reassert racial dominance.”

Longstreet stood in stark contrast. Varon shows that “It was not the battle at Gettysburg that defined Longstreet’s Civil War but rather the surrender at Appomattox.” He accepted, as no other leading Confederate did, that the honorable thing to do was enact the political and economic agenda imposed by the north. He never renounced his racism — he owned eight slaves from the age of 11, advocated for slavery’s expansion and kept company with radical advocates. He continued to hold humans in bondage even while an active-duty Army officer and brought two with him on deployment to Comanche territory. He directed that captured free Blacks be enslaved (more than 1000 during the Gettysburg campaign alone!) and defended slavery as late as 1864. After the war he wanted a whites-only, states-rights Republican party. But Longstreet also believed that “there can be no discredit to a conquered people for accepting the conditions offered by their conquerors.” He argued the south should “come forward, then, and accept the ends involved in the struggle.”

As a post-war elected leader in New Orleans, Longstreet hired black soldiers as police and led voter registration drives for blacks. And he physically defended the Black community during the 1873 Colfax massacre, which was the single bloodiest day during Reconstruction. Varon recounts the sad denouement as violence overtook Reconstruction: murderous intimidation of Black voters, Republican politicians, and northern businessmen throughout the south; Supreme Court decisions narrowing protections against racial violence; and public weariness even in the north of the burden of military occupation. Longstreet abandoned working to advance Reconstruction in 1875 and moved to Georgia.

The death of Lee removed the last restraint on vilification of Longstreet. Because while Lee disapproved of Longstreet’s politics, he would not deny Longstreet’s war record. Nor did other Confederate leaders contemporaneously. After Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, Lee singled out Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell for halting execution of the Confederate advance, but not Longstreet. After William Tecumseh Sherman’s success against Longstreet in the Tennessee campaign, Longstreet offered his resignation and Confederate President Jefferson Davis refused, needing competent commanders amidst feuding among the generals in the western theater. Lee wrote Longstreet an admiring letter on Feb, 25, 1865 demonstrating the continued confidence he had in him just six weeks before surrendering at Appomattox:

We might also seize the opportunity of striking at Grant, should he pursue us rapidly or at Sherman before they could unite. I wish you to consider this subject and give me your views … I wish you would watch closely his movements on the south side of the run, and try to ascertain whether he is diminishing his force … I should very much like to confer with you on these subjects, but I fear it will be impossible for me to go south of the James River, and I do not know that it will be convenient for you to come here.

So it is difficult to credence post-war derogation of Longstreet’s wartime performance. But Longstreet was querulous, disputing credit among Confederate generals from the first battle of the war. Still, his strategy was better suited to Confederate strengths and weaknesses than was Lee’s: Longstreet’s preferred approach in battle was “allowing the enemy to attack a fortified position, then counterattack a weakened foe.” Of Gettysburg, Longstreet said “My idea was to throw ourselves between the enemy and Washington, select a strong position, and force the enemy to attack us.” Yet he yielded to Lee on Pickett’s Charge and refused Gen. John Bell Hood’s requests for changes. Varon has done a great service by unearthing the political motivations for lost cause mythologists castigating Longstreet and chronicling the timing and therefore revealing the purpose of the alternative history with which he’s painted.

In War Music, Christopher Logue’s magisterial retelling of the Iliad, Hector’s smart wife Andromache is lovingly compared to Helen of Troy: “From diadem past philtrum on to peeping shoes, / You show another school of beauty.” I hear it echo as Varon’s biography of Longstreet shows an alternative American history, one where the “lost cause” myth isn’t permitted to sink roots, where Confederate flags are disdained rather than brandished, where there is no question that slavery was the cause of the Civil War and its advocates shunned in public discourse and scorned from elected office. But that is not the legacy we continue to live.

The Naming Commission was mandated by Congress in the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act to “remove all names, symbols, displays, monuments, and paraphernalia that honor or commemorate the Confederate States of American or any person who served voluntarily with the Confederate States of America from all assets of the Department of Defense.” Commissioners spanned the political spectrum from a serving Republican congressman of Georgia to the activist author of a book about the moral necessity of purging Confederate memorials. Retired Adm. Michelle Howard, the chair we commissioners selected, led us by drawing out consensus on decision rules: We would interpret our mandate narrowly — rename the 10 Army bases and capital ships, and set standards for military academies — and committed to making all our recommendations unanimous. For new names, we would show a preference for people who soldiers could emulate. We wanted enlisted and non-commissioned heroes rather than only generals. We wanted Medal of Honor recipients from more recent wars and from communities that had been overlooked. We met with affected communities, took their and other public suggestions, and listened to soldiers stationed at the posts.

What that process produced was the recommendation for renaming 758 items at military installations, and a suggested list of 90 exemplary candidates. We offered specific recommendations for the 10 Army posts and two ships. Ft. Rucker, which had been named for a Ku Klux Klan leader, was renamed to honor Chief Warrant Officer Michael J. Novosel, a Medal of Honor recipient from the Vietnam War who flew over 2,000 medevac extraction missions. Ft. Benning was replaced with commemoration of Lt. Gen. Hal Moore of We Were Soldiers Once fame and his wife Julia Compton Moore, who revolutionized casualty notification practices in the Army.

It’s shocking that it took so long to stare unblinkingly at the racism of commemorating the Confederacy. That we — including me — thought so little of what that communicated about us, especially to those Black Americans who chose to risk their lives for our country, is terrible. And there has been widespread acceptance of the new names. Yet Republican presidential candidates Mike Pence, Ron DeSantis, and Donald Trump all said on the campaign trail that if elected they would rescind the renaming. Varon’s book reminds us how we came to be where we are, and how much work remains to be done: There are more than 4,400 American names etched into those plinths in Montgomery, all killed by their fellow Americans after Longstreet gives up trying to win the peace of the American Civil War.

–warontherocks.com