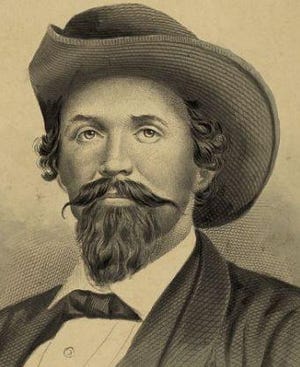

Bent slightly in stature, balding steadily and a bit on the heavy side, John Hunt Morgan was not that impressive to the casual viewer.

By only looking at the man, one would miss was the extraordinary charisma of this most impressive of generals.

By the summer of 1863, America had been in Civil War for two years. Confederate armies had won repeated victories in the east at Bull Run, Fredericksburg and a draw at Antietam. In the west, initial victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson had been checked at Shiloh.

But with determination, the Union Army was moving south. And in the east, a new Union Army was on the move, as well.

What was the Confederacy to do? Morgan thought he had an answer. Leading a force of 2,500 men, he came north to the Ohio River hoping to lure Union armies to chase him and keep reinforcements away from Grant in the west and the Army of the Potomac in the east.

The Union did not take the bait, and Morgan found himself with an army and no place to put it. Defying orders from his commander, Gen. Braxton Bragg, Morgan crossed the Ohio and began a raid of pillage and destruction across southern Indiana. Achieving his objective, Morgan eventually had more than 100,000 men in pursuit of his troops.

Scavenging his way across southern Indiana and Ohio, Morgan captured thousands of prisoners, read them their rights and released them on parole. He stole thousands of horses, beeves and sheep to feed his army.

He also had a large army chasing him that consisted not only of recently mobilized Union Army troops but also thousands of citizen militia men.

Morgan moved south and hoped to make a crossing of the Ohio River at a low place in the water called Buffington Island. The Union Army was waiting, and in a pitched battle, Morgan’s force was turned back.

Now leading only a few hundred men, Morgan turned north and tried to find another place to cross back into the Confederacy. He did not find it and was forced to surrender near Salineville in eastern Ohio.

Most of Morgan’s men were sent to the Camp Chase Confederate prison camp near Columbus, and many became ill in the poor conditions and died.

Morgan and seven of his officers were housed in the “escape proof” Ohio State Penitentiary. The men were housed in small stone cells with large cast-iron doors. Confederate Capt. Thomas Hines noticed a slight breeze in his cell and soon discovered it came from a break in the caulking of the stone.

Moving a flagstone, Hines soon saw an air duct under his cell. Crawling in and following the duct, he came to a dead end of earth and stone. Over the next several days, he and his friends cleared the stone, and he climbed out of the tunnel and found himself near the corner wall of the prison.

In the next few days, the Confederate prisoners found their way through the air passage and over the walls to freedom. In later years, it was said that they must have had help from outside the walls to keep guards distracted and the walls clear to escape.

Dressed in civilian clothes, Morgan and Hines boarded a train from Columbus to Cincinnati. Seated next to a Union officer, Morgan was told, “Well, there sits Morgan for ‘safe keeping.’” To which Morgan responded, “And I hope they will keep him as safe as he is now.”

Arriving close to Union Army checkpoints in Cincinnati, Morgan and Hines left the train and hired a boatman to ferry them across the Ohio River. Morgan reached his home and was welcomed by family and friends.

Morgan soon was in command of a new force of Confederate cavalry and undertook a new series of raids. At a place called Yellow Tavern in 1864, Morgan and some of men were surprised by Union cavalry, and he was killed.

Morgan is buried near the family home in Lexington, Kentucky. Many of his men are buried in the Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery at the corner of Hague and Sullivant avenues in Columbus.

The story of the Morgan still is prominent in Lexington. His home, the Hunt-Morgan mansion called Hopemont, was built in 1814 by John Hunt, the first millionaire west of the Allegheny Mountains. The Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation was founded in 1955 and saved the house from demolition. The house is now a museum and open to tours. A statue of Morgan on the courthouse lawn was moved to the Lexington cemetery in 2018.

Local historian and author Ed Lentz writes the As It Were column for ThisWeek Community News and The Columbus Dispatch.

–dispatch.com