SOUTH CAROLINA: Papers of 1st Post-Civil War Governor Finally Returned to S.C.

COLUMBIA — The papers of South Carolina’s first post-Civil War governor are back home and publicly available in the capital city after spending more than a century in Alabama.

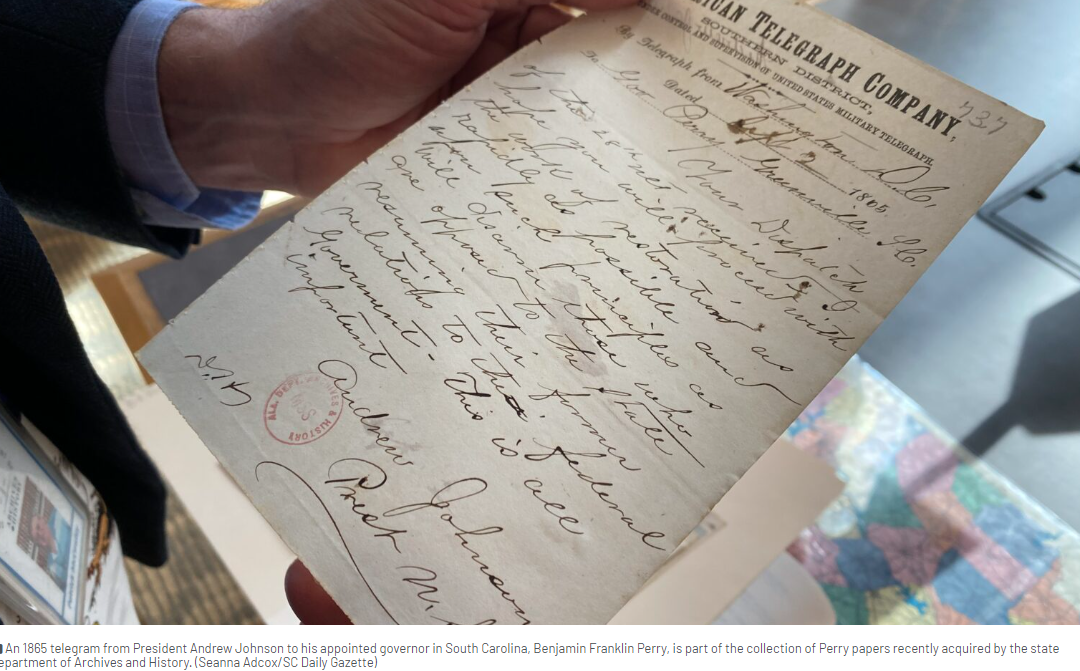

Benjamin Franklin Perry was governor for just six months at the appointment of President Andrew Johnson, when he oversaw the creation of a new state constitution that recognized the end of slavery. He also successfully advocated for ratification of the 13th Amendment — as Johnson required to rejoin the United States.

The South Carolina Legislature’s reluctant agreement in November 1865 proved crucial to the U.S. Constitution formally abolishing slavery a month later, when Perry’s term ended.

But Perry, a controversial figure throughout his political career, was certainly no friend to freed slaves.

The extensive correspondence and writings preserved by his family — 11 cubic feet worth — were recently acquired by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History at no cost from Alabama’s state archives.

Exactly when the collection made its way to Alabama is unclear. At some point, Perry’s son, William Hayne Perry, moved to Alabama and took the papers with him. His wife’s sister was the longtime director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, which acquired them piecemeal over decades from the family.

In 2022, South Carolina officials sought a transfer, making the case that the papers should be more accessible to historians in Perry’s home state. After a review found that nearly the entire collection related to South Carolina’s history, the governing board of Alabama’s agency agreed last summer.

The collection spans the Perry family from 1722 to 1977, though the bulk of the documents cover the life and career of Gov. Perry, according to the South Carolina agency.

It helps complete the agency’s records of South Carolina governors.

“This collection provides valuable information about South Carolina politics at a crucial time in the state’s history,” Eric Emerson, director of South Carolina’s agency, said when announcing the transfer last month. “It is especially valuable in bridging the gap between the records of the state’s Civil War governors and the Reconstruction-Era governors who followed Perry’s administration.”

Emerson actually picked up the papers in October and drove them to South Carolina.

Why did Johnson pick him?

Perry’s public career started in 1830 as a pro-Union newspaper editor who publicly opposed nullification and, later, secession. In 1832, he even fatally wounded a pro-nullification editor of another newspaper in a duel. He was first elected to the state House in 1836 and spent three decades in the Legislature before Johnson named him provisional governor.

But he was no abolitionist. His arguments for remaining in the Union were economic.

Once the war started in South Carolina, he became a prosecutor and judge in the Confederate government. He even had a military title, though historians don’t believe he actually fought in battle.

The state constitution created during his tenure specifically denied voting rights to freed slaves. Its limited democratic reforms included removing land ownership requirements for legislators, more equal distribution of legislative districts, and electing the governor by popular vote, rather than by the General Assembly.

Eligible voters, however, remained white men only.

The 1865 constitution is still fairly significant in transitioning South Carolina from a defeated Confederacy and adding some democratic principles as the state attempted to rejoin the United States, said Patrick McCawley, deputy director of the state archives agency.

But Perry “wasn’t open to political equality for African Americans,” he said.

On the contrary, he advocated for the Black Codes, a series of laws passed by the Legislature after the 1865 constitution’s adoption that severely limited the freedom of all African Americans. One barred Black residents from being anything other than a farmer or servant without paying an annual, intentionally unaffordable tax.

Perry was elected to the U.S. Senate following passage of the 1865 constitution. But the Republican-controlled Congress refused to recognize him and other former Confederates newly elected to Washington from the South under Johnson’s lenient Presidential Reconstruction plans.

That led to Congress taking control of reunification from Johnson and sending federal troops to the South for what became known as Radical Reconstruction, McCawley said.

Gov. James Orr, who replaced Perry as the first publicly elected governor in South Carolina, was deposed and replaced by an acting military governor until a constitution was passed to Congress’ liking.

The state constitution rewritten in 1868 by a majority-Black convention of delegates undid the Black Codes and promised free education for all children and voting rights to all men — something Perry continued to publicly oppose. Congress readmitted South Carolina to the Union that summer.

Perry later supported the election of Confederate Gen. Wade Hampton as governor in 1876, which brought about the end of Reconstruction and the reversal, again, of freedoms for former slaves.

Perry died at home in Greenville in 1886, nine years before the state’s last constitution ushered in the Jim Crow-era South.

His papers are available for research during regular visitor hours at the state Department of Archives and History, Tuesdays through Saturdays 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Steve Murray, director of Alabama’s archives agency, said it was only right to return the Perry collection to South Carolina.

“If the situation were reversed, Alabama would desire to see the return of a former governor’s papers to Montgomery, so they could be accessible to researchers and educators,” he said.

–scdailygazette.com