SOUTH CAROLINA: A Confederate Statue Fight Renewed: How this S.C. City is Looking to the Future

Thirty years after a monument honoring Confederate soldiers was erected in the middle of Main Street in downtown Greenville, the marble statue atop a soaring granite base was moved to a newly constructed small park a block away. That was 1924. It’s been there ever since, its back to Springwood Cemetery, where 80 Confederate soldiers, identities unknown, are buried.

Protesters have decried the statue; supporters have honored it. Greenville community activist Bruce Wilson has renewed the call to remove the statue, telling City Council members recently it’s time to act.

“There is no doubt that the Confederate statue is nothing but a relic of the past — a relic of hatred and racism that was designed to intimidate free Black individuals from the time beyond Reconstruction. And here we are in 2022 with those same symbols,” he said.

Twice before, a contingent has pressed for removing the statue — five years ago and two years ago after civil unrest occurred elsewhere. Protests broke out at the statue after George Floyd was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis.

As other cities around the country have taken down their monuments, Greenville city officials continue to wrestle with what to do with theirs. For more than 20 years, the South Carolina Heritage Act has prohibited removing or altering statues, memorials, roads honoring any war, from the Revolution to Persian Gulf, Native Americans or African Americans. It was passed as a compromise when the Confederate flag was taken down from the State House dome.

GREENVILLE’S CIVIL WAR TRIBUTE

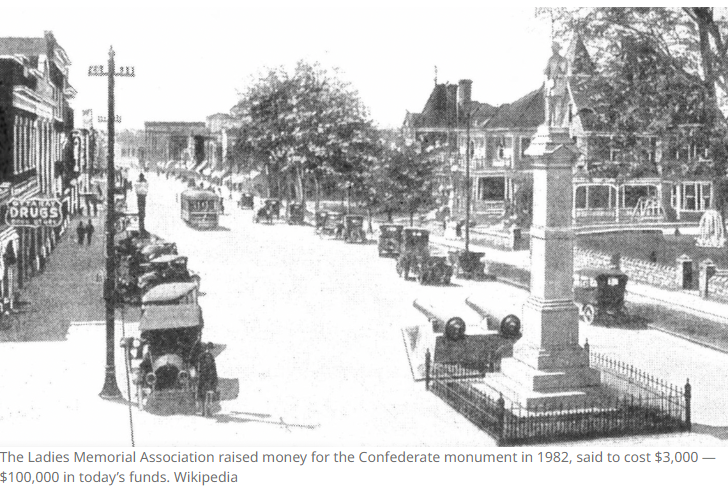

The monument was erected in 1892, 27 years after the Civil War ended in the later years of Reconstruction. The State newspaper called it “one of the handsomest and costliest in the South.”

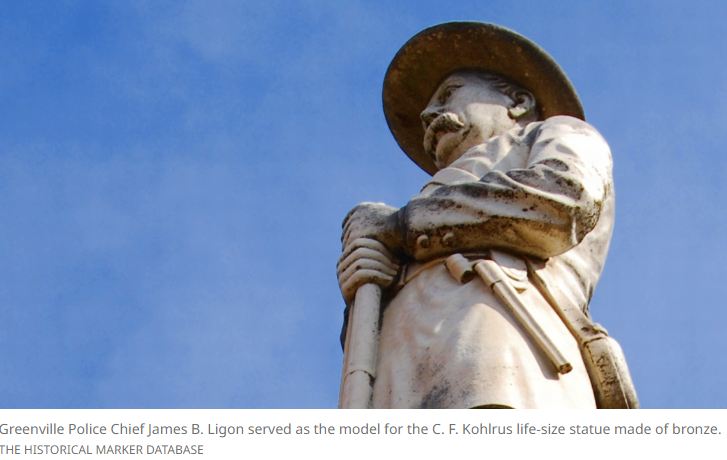

Greenville Police Chief James B. Ligon served as the model for the C. F. Kohlrus life-size statue made of bronze. Ligon had fought in the Civil War, one of the first in Greenville to volunteer. The Ladies Memorial Association raised money for it, said to cost $3,000 — $100,000 in today’s funds.

It was a big day — a parade, bands, speeches. Thirty years later it was an impediment to traffic. When city leaders proposed moving it, townsfolk rose in protest. City officials took it down and hid it in a barn for two years until the South Carolina Supreme Court ruled the city could do what it wanted to with its streets. Placing it elsewhere would give honor to the “sermon in stone,” the ruling said.

MEMORIALS ACROSS THE U.S.

The Southern Poverty Law Center says there are 2,089 Confederate memorials in the United States and its territories, South Carolina has 60, plus dozens and dozens of streets and schools named for Confederate generals. Among the many memorials in Columbia is a Robert E. Lee magnolia tree, planted 10 days after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the idea of separate but equal public schools.

Fort Mill has a monument in its Confederate Park to “loyal slaves,” who were said to protect women and children while men went off it war. The city also has memorials to women and veterans of the Civil War. Two years ago after complaints about the slave memorial from some in the community, the City Council voted to explore what could be done.

In the years since 2015 when Dylann Roof murdered nine people at a Bible study at Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, more than 300 Confederate symbols have been removed across the country, including 170 monuments, the Southern Poverty Law Center said in its report called “Whose Heritage?”

Kimberly Allen of the Southern Poverty Law Center said removing such memorials is an important first step toward overcoming hate and white supremacy.

“White supremacy reveals itself through various symbols that represent some of the most harmful and brutal aspects of U.S. history,” she said. “The public presence of these racist symbols only serves to uphold the belief that white supremacy is still morally acceptable, giving life to the false narrative that the Civil War was fought for something other than to preserve chattel slavery.”

Seven states have laws like South Carolina’s Heritage Act — Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee — enacted between 2000 and 2021.

“Regressive preservation laws like the Heritage Act deny communities the right to make their own decisions about what they want to see in their public spaces,” Allen said. To great fanfare, Charleston took down a stone and metal statue of John C. Calhoun in 2020, a congressman and vice president who called slavery a “positive good.”

The 125-year-old statue was in the highly visible Marion Square but was considered to be privately owned, making the Heritage Act moot. A marker honoring Robert E. Lee was removed in 2021, with Charleston city officials arguing the Heritage Act protects memorials to specific wars. “Robert E. Lee is not a war,” city officials said at the time.

A charter school with a majority minority student population on the property where the marker was located asked that it be removed.

GREENVILLE AND THE HERITAGE ACT

In Greenville, state Rep. Chandra Dillard, a former City Council member, said she believes each community should have the opportunity to decide for itself what sort of monuments and markers they should have. Dillard was instrumental in getting a statue erected on Main Street in Greenville in 2006 to honor Sterling High School and the civil rights movement. It was the first to pay tribute to the Black community in Greenville and is positioned close to the location of the former Woolworth’s, where sit-ins took place for three weeks in 1960 to oppose the whites-only lunch counter.

Dillard has served as a sounding board for the city on ways to honor Greenville’s African American history. She has declined to introduce legislation to take down the Confederate statue saying it doesn’t have a chance at passing. Efforts to repeal the act, to amend it or allow individual communities to change anything have died in various committees. The only change came in 2021, not from the legislature but the state’s highest court.

The South Carolina Supreme Court ruled a simple majority, rather than two-thirds, could amend the act. Jennifer Pinckney, widow of the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, one of those murdered at Emanuel Church, was among the plaintiffs in the lawsuit that sought to overturn the act. The court ruled the law was constitutional. Dillard said a better plan for Greenville would be to gather a committee to consider other possibilities. Perhaps a statue alongside the Confederate soldier to honor Black history in some way. Some have proposed moving the statue inside the park, but Dillard said the area where the statue is located remains part of Springwood Cemetery — the fence was just moved when the park was built.

Greenville Mayor Knox White said the city wants to focus on something more productive than arguing about a statue that they can’t do anything about. He does think a local government should be able to determine what symbols they want to embrace. He called the inscription on the Confederate statue offensive in that it glamorizes the war. Among the lines on the base of the statue are “The world shall yet decide/in truth’s clear far off light/ that the soldiers/ who wore the grey and died/with Lee, were in the right.”

He said he wants to tell the whole story of African American’s contributions to the city with an interpretive monument of some sort. That would add to the Sterling statue, Unity Park and a huge mural on the side of an eight-story building depicting Pearlie Harris, the city’s first Black teacher in an integrated school.. “It’s a step by step effort to be inclusive,” he said.

–thestate.com