TENNESSEE: U.S. Colored Troops Statue Unveiled in Downtown Franklin

In November of 1899, a group gathered on Franklin’s town square. Thirty-five years after the end of the Civil War, the United Daughters of the Confederacy had raised the funds to build a Confederate soldier statue, and the crowd that day gathered to celebrate “our heroes in gray,” as the inscription read, in part.

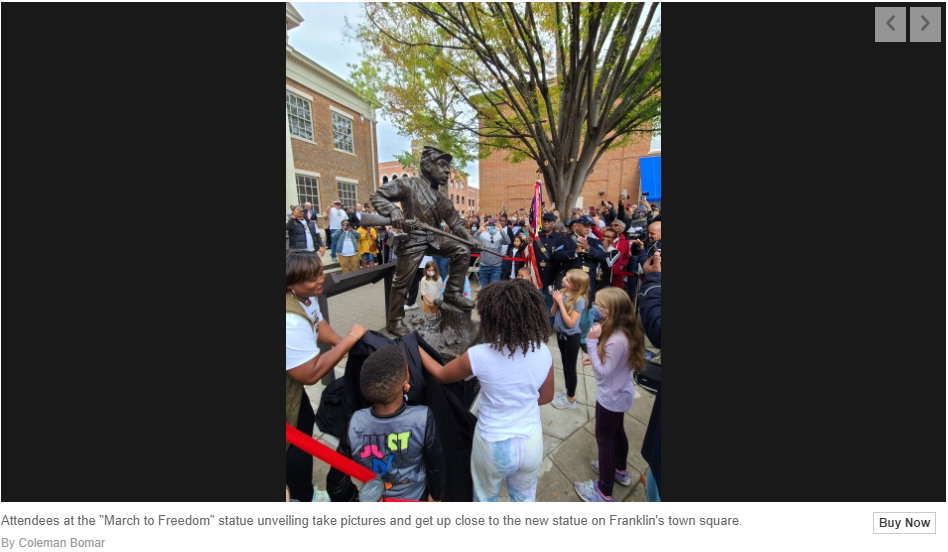

On Saturday, 122 years later, a group of hundreds gathered on that same town square to dedicate another monument.

Entitled “March to Freedom,” the bronze statue depicts a United States Colored Troops. His gaze looks forward, conveying a sense of determination.

Entitled “March to Freedom,” the bronze statue depicts a United States Colored Troops soldier carrying a rifle, with one foot propped on a stump. At his feet lie shackles; his gaze looks forward, conveying a sense of determination.

“We didn’t want him on a pedestal 20 feet in the air,” said Pastor Chris Williamson of Strong Tower Bible Church, speaking to the crowd outside the former Williamson County Courthouse. “We wanted him down on our level, where you could see him. … Above all, you could see his personhood.”

West Harpeth Primitive Baptist Church Rev. Hewitt Sawyers was born and raised in Williamson County during the days of segregation. He recalled ordering food from restaurants on Franklin’s Main Street through the alley door, sitting in the segregated section of the Franklin Theatre and drinking from the colored water fountain near the very spot he stood Saturday.

“I was conditioned, in other words, to know where my place was,” he said.

Sawyers recalled driving into Franklin with his father as a boy.

“When we drove in here, the only thing you would be able to see was Chip when you drove down the street,” he said. “The imagery that I saw as a boy, that shaped me to where my place was; I want to tell you now that we have a different imagery here. We have markers that are telling a different history. We have a statue here that’s telling us it’s a new day. It’s a brand-new day. Things are not changing; they have already changed.”

Telling the Fuller Story

The statue is the capstone of the Fuller Story project, which included adding historic markers on Franklin’s town square explaining more of the area’s history. Among that history was a slave market located where the courthouse is today, a race riot and the location of the freedmen’s bureau.

The Fuller Story took root in 2017 after news broke of the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

That event spurred Battle of Franklin Trust Director and Historian Eric Jacobson to find a way to share more of Franklin’s untold stories about enslaved people and how emancipated slaves joined the United States Army to fight for freedom.

Jacobson met with pastors Kevin Riggs, Sawyers and Williamson, who agreed that the answer to dealing with Franklin’s difficult history was not to hide painful parts of the story, but to share more of the greater story with the hopes of healing.

So, instead of looking to take down the Confederate statue at the center of the square, they started a movement to build another statue, one which would represent the Black men who fought and died for their nation and their freedom.

Riggs, a white pastor, said he heard skepticism from members of the Black community who didn’t believe they would be able to place an African American statue in the most prominent spot in town. Riggs divided the project up into three phases: “Impossible. Possible. Done!” he said.

On Saturday, Franklin Mayor Ken Moore and City Administrator Eric Stuckey expressed their support and pride for the project.

“God’s creation is diverse, and it’s beautiful, and I’m seeing a snippet of it right here,” Stuckey said.

Stuckey also reminded the crowd of a great advocate for the Fuller Story: former Alderman Pearl Bransford, who died of cancer in November 2020. The reveal of the statue Saturday, Stuckey noted, aligned with her birthday.

Each of the three pastors spoke about their journeys with the Fuller Story before Jacobson explained who the United States Colored Troops were and the role they served.

The troops were formed through a clause in the Emancipation Proclamation which allowed enslaved men to join the United States Army to fight for their freedom and the country in which they were born and hoped to soon become legal citizens. Between 180,000 and 200,000 Black men joined the Army, comprising 10% of its troops. They fought in major campaigns like the Battle of Nashville, Vicksburg, Richmond and Appomattox Court House.

Jacobson quoted an 1852 speech from Frederick Douglass in which the abolitionist challenged listeners to live up to the creed of the nation’s founding.

“He knew the purpose and the intent of the founding, but he was challenging the white community to stand up and live up to the promise of the Declaration and of the Constitution,” Jacobson said. “Franklin has led the way in many efforts. I think this is Franklin’s proudest day, and proudest achievement.”

Williamson echoed the sentiment.

“I’m glad Franklin is making national news for something good,” he said. “[God] has a way, an impeccable way, of taking painful things in our history, like slavery, like war, and working it to a redemptive end.”

Williamson instructed the crowd on how to respond when their children asked, “What does this statue mean?”

“This statue represents the nearly 200,000 men who bravely fought for our country, for their freedom and for the freedom of 4 million enslaved people in our country,” he said. “This statue means hope, it means courage, it means possibility, it means dignity, it means valor. As Pastor Sawyers said, it means a new day.”

The mood during the unveiling was one of joy and excitement. Between speakers, ensemble group Kettle Praise and singer Adrianna Clemons sang spiritual songs as onlookers lifted their hands in praise. Many wept.

Sculptor Joe Howard, who lives in Columbus, Ohio, but was born in Paris, Tennessee, drove down with the statue for the weekend. He paused a minute to take in the scene before counting down with the crowd to the unveiling.

Several young children pulled a sheet off the statue in unison. The crowd, many of whom were filming the moment, reacted with whoops and yells before Kettle Praise sang one last spiritual: “Ride on, King Jesus. No man no can hinder thee.”

–williamsonherald.com