ALABAMA: Courthouse Resolution Sparks Debate Abouut Confederate Monuments

Earlier this month the American Bar Association urged state and local governments to remove Confederate memorabilia and other symbols from courthouses.

It’s being met with skepticism in deeply conservative Alabama, where 180 live memorials to the Confederacy still exist including nearly two dozen at county courthouses.

The ABA resolution could spark renewed attention on the existence of Confederate monuments and images near the halls of justice.

“These racist relics do not accurately reflect our shared American experience and, most importantly, promote the exact opposite of what equal justice should look like,” said Tafeni English-Relf, director of the Montgomery-based Southern Poverty Law Center’s Alabama State Office.

Critics are dismissing the ABA’s resolution, and the organization itself as having a left-leaning bent on highly-charge cultural issues like gun control, abortion, and same-sex marriage.

Representatives with the Sons of Confederate Veterans also blast further pursuits to have Confederate images removed in Alabama as a waste of taxpayers’ money. They also claim they have the law on their side: The Alabama Memorial Preservation Act, approved in 2017, making it illegal for anyone to remove or alter an “architecturally significant monument” 40 years or older from a public place. A $25,000 one-time fine is often associated with a monument’s removal.

The Alabama State Bar Association is also keeping its distance from the ABA resolution. A spokeswoman with the Alabama State Bar says that while the ABA is a “voluntary trade association of lawyers” free to take a position on issues, the Alabama State Bar is a licensing and regulatory agency required to comply with state and federal laws. That prevents it from taking public positions on policy issues.

Melissa Warnke, a spokeswoman for the Alabama State Bar, said removal of “certain Confederate era symbols” implicates the 2017 law.

Courthouse battles

The battles over Confederate monuments outside or near the courthouses are not quieting, even about three years after a spirited debate to have a Confederate monument relocated from the Madison County Courthouse in Huntsville.

Some of the recent disputes are playing out within courtrooms:

- A Macon County judge ruled last month that a Confederate soldier monument be removed from a park in Tuskegee that is a “stone’s throw” from the county courthouse. An attorney representing a Confederate heritage group is appealing the ruling to the Alabama State Supreme Court.

- A judge in Lauderdale County in November dismissed a lawsuit seeking an injunction from removing a Confederate monument in front of the county courthouse. The judge ruled the lawsuit moot, saying that Lauderdale County officials confirmed they have no intentions of moving the monument and will fully comply with state law.

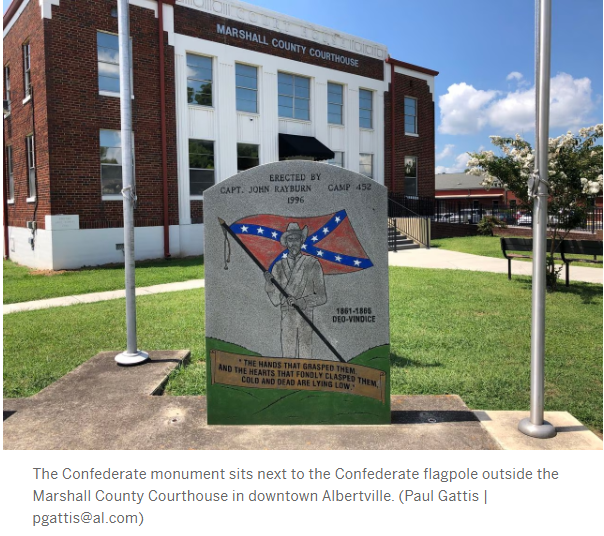

- Marshall County officials built a fence around a Confederate monument outside its courthouse in Albertville, and in late 2020, adopted a controversial resolution regulating protests on county property.

Unique Dunston, founder of Reclaiming Our Time – the organization pushing the hardest for the removal of two Marshall County monuments – said she is appreciative of the ABA’s resolution but does not feel it will carry much sway in conservative counties.

Marshall County is a staunch Republican area in which over 83% of voters in 2020 voted for former President Donald Trump.

Said Dunston about the ABA’s resolution, “it is another opportunity to continue the conversation concerning the Confederacy and its symbols of white supremacy. We have not given up on our efforts to have both Confederate monuments in Marshall County relocated.”

Whose Heritage?

Police prepare to advance on protesters during a George Floyd protest at the Madison County Courthouse on June 1, 2020. The Confederate monument is seen in the background. (Paul Gattis | AL.com)

Macon County is different. Located in Alabama’s “Black Belt” region, the county is 80% Black, while Tuskegee is 97% Black. The monument has been the subject of on-and-off protests for years and attempts to remove it date back before the recent national push to have Confederate monuments and imagery removed.

Circuit Judge Steven Perryman ruled last month that the site where the Confederate monument has stood since 1909 should revert to the Macon County Commission.

Perryman’s ruling was based on the terms of a 1906 deed that gave the space to the Tuskegee Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy for the purpose of maintaining a “park for white people” and “maintaining a monument” to Confederate soldiers.

Perryman, in his ruling, said there is no evidence the space has been maintained a segregated park. He said the terms of the 117-year-old deed shows that the land should revert back to the county since it was not being used as a “park for white people.”

A Confederate monument in Tuskegee, Ala., is shown with its base wrapped in tarps on June 12, 2020. A judge ruled in January 2023, for structure and its surrounding park is ongoing and will be considered by the Alabama Supreme Court. (AP Photo/Kim Chandler)AP

Jay Hinton, a Montgomery-based attorney representing a Confederate heritage group fighting against the ruling, said he does not believe the deed is enforceable, adding that the Tuskegee chapter “for 315 years, has not kept people off the park.”

“We’ve allowed people to use it for all of those years,” Hinton said. “The court ruled that we violated deed language because we didn’t keep Blacks off the park. It’s a horrific ruling. Society ought to think so as well.”

Macon County Commission Chairman Louis Maxwell said the focus for Tuskegee is for the county to take ownership of the property, and then decide “what goes on the property.” He said the county commission is “not interested” in seeing the monument destroyed and will work with groups to have it relocated.

“We contend this is public property and it’s for the citizens of Macon County,” Maxwell said. “Our goal is we want to get this matter resolved once and for all.”

He also claims that the Tuskegee Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy “no longer exists,” and there is no provision to have it transferred to a Confederate heritage group not located in Macon County.

“The closest (similar group) we found was in Andalusia,” he said.

Attorney Fred Gray Jr., who is working with his father – civil rights icon Fred Gray Sr. – to get the issue resolved, said he finds it troubling the Tuskegee chapter no longer has a member living within the city.

“It just goes to show that they just want to control the very image of what goes out from this particular city,” said Gray.

Maxwell said he is concerned about having the case appealed to the Alabama State Supreme Court, where all 10 justices are white, and a Democratic justice has not served since 2011.

“I pray they will just be fair and look at the facts and make a decision based on that,” he said.

Gray said he will focus on the merits of the case, and the questionable deed.

But he said a Confederate monument near the courthouse underscores a problem.

“It certainly goes against true justice for all the people,” Gray said.

–al.com