SOUTH CAROLINA: Camden Historical Advocate Passes Away

CAMDEN — Two things stick out immediately on the tree-lined southbound road leaving Camden.

There’s the towering stands of Zemp Stadium, where the community’s powerhouse high school football team plays beneath reminders of glories past. Several hundred yards away sits the white-washed colonnades of the Kershaw/Cornwallis House, the home of the town’s founder and county namesake, Joseph Kershaw.

For years, the Kershaw House stood as a modest tribute to the city’s past, yet today the site has come to life. Workers recently fired up a kiln to build period-correct bricks for a pathway running through the 107-acre park. Children rushed from outbuilding to outbuilding, laughing as they placed their arms and heads into replica stockades at the center of the makeshift town. As they played, a small film crew meandered through the site, preparing principal photography for a movie about the battle that took place there.

It may have been Kershaw who founded the community. But it was his descendent, Virginia Dewitt Zemp, who rebuilt it.

Zemp, a longtime member of South Carolina’s preservation community, died earlier this month at age 60. She spent many childhood summers with family in Camden before moving to Charleston, where she quickly established herself as a key figure in historic-preservation efforts there.

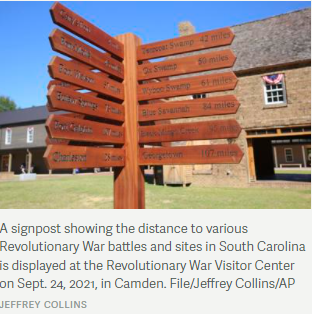

Three years ago, however, Zemp would leave Charleston for a position leading Historic Camden and its broader mission of reviving South Carolina’s oldest, inland settlement as a focal point of a planned “Liberty Trail” crisscrossing the state’s Revolutionary War sites ahead of the state’s 250th birthday in 2026.

“She was very much looking for this to be a capstone opportunity that would allow her to have a really big impact,” said Andy Morse, Zemp’s partner and director of development at the Revolutionary War history organization, The Society Of The Cincinnati.

Zemp sought out practical artifacts from the earliest days of Camden’s settlement, building out a blacksmith, a brickworks and a drill plow.

She recruited tradespeople to work the sites, and initiated conversations to turn the facility’s replica 18th-century tavern into a full-time operation serving coffee, tea and other beverages.

She oversaw the purchase of the original battlefield and put in motion the transfer of even more historic structures to the site in an effort to rebuild the town after years of stagnation.

“It’s certainly a livelier place than it was,” Lynn Teague, a lobbyist for the South Carolina League of Women Voters and former archaeologist who knew Zemp, said of Camden.

Most importantly, Zemp brought in money and a vision of how South Carolina’s birthday stories should be told.

“We were just about ready to strut our stuff,” Historic Camden’s preservation director, Cary Briggs, said in an interview. “But then, unfortunately, we lost her.”

Zemp died of a heart attack in mid-February after a little more than two years at the helm of Historic Camden. But friends and colleagues say in that short time, Zemp helped reinvigorate an effort to preserve the state’s Revolutionary War history that has long been neglected by state and federal leaders, laying out a template for preservationists across the state to pursue in reminding the public of South Carolina’s integral role in securing American independence.

“She was really brought up here to help with our vision,” Briggs said. “Even though she was here a short period, she really gave this place a new direction.”

Camden and the backcountry

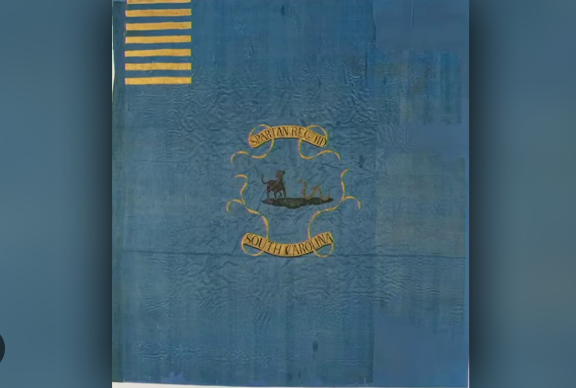

To understand Camden’s significance in South Carolina history is to understand the origin story of an entire nation. While the manicured fields and wooded valleys of New England were where the war began, it was in swamps and the forests of the South Carolina backcountry where the war was won.

But for more than a century, the region’s role in the conflict would fade to seeming obscurity against the emotional and physical tolls of the Civil War, the first shots of which were fired in the Palmetto State. The historic sites of Camden would fall into neglect.

“I grew up in one of the richest Revolutionary War communities in the country and knew nothing about it,” said Vincent Sheheen, a Camden native and its longtime representative in the South Carolina Senate before his primary defeat in 2020. “And, you know, our obsession with the Civil War in the state really allowed the nation to forget about what happened in the South and what happened in South Carolina.”

At the time, the people of Camden were caught between growing revolutionary fervor in the Lowcountry and a burgeoning population inland, where many remained loyal to the crown for the free land and equipment they’d been granted to cultivate the untarnished landscape and the business connections bearing promises of prosperity.

As the fever of war burned along the coasts, inland settlements like those in Camden would be left largely untouched throughout the early years of the conflict. That was, until the conflict came to them. The South Carolina backcountry would soon become the focus of the British campaign to end the war, with Camden — Kershaw’s mansion, specifically — becoming the base of operations for Gen. Charles Lord Cornwallis in the region.

Camden itself would become the site of what is largely considered among the Colonies’ worst defeats of the war, and the end of American Gen. Horatio Gates’ storied military career following a disastrous retreat. But it would also be a wake-up call for a beleaguered Patriot army to take a new approach to combat that would secure American independence.

“The battles in South Carolina were very pivotal,” said Morse. “Even though Camden was a horrible defeat, it was a pivotal part of the chain of events that helped Cornwallis get seduced out of the South. The story of the war could have ended very differently if what occurred there never took place.”

Building for the future

But for its significance, the years would not be kind to historic Camden. The 100-plus acres of the old town would become a garbage dump, the site’s curator Nathan Brazell said on a recent tour of the site.

Kershaw’s mansion, burned by Union Gen. William T. Sherman’s men at the end of the Civil War, would remain missing from the landscape until rebuilt in the larger preservation campaigns of the late 1970s, when urban renewal in American cities sparked widespread preservation efforts across the country.

Little more would happen in Camden after that. A handful of historic homes would be moved to the site and signage erected. But proponents say the historic Camden site lacked both the vision and investment necessary to return to its full glory.

Camden’s neglected state was not uncommon. As the new millennium approached, many key sites in Revolutionary War history had fallen into disrepair, putting the tangible symbols of America’s heritage at risk of being lost forever.

In the mid-1990s, Congress declared the historical integrity of many Revolutionary War and War of 1812 sites were at risk and in need of substantial study and reinvestment to preserve them. Lawmakers appropriated funding to identify the sites most in need of repair and, in 2007, received a list of 30 high-priority battlegrounds at the highest level of risk.

Camden — a “Class A” battlefield at medium risk — was among them.

Though a native of Camden, Sheheen said he never truly understood the significance of the site until a friend invited him to tour the actual site of the battle, a woodland of more than 400 acres where British and American forces first clashed in the dead of night before the next day’s disastrous skirmish. It was then Sheheen realized the community had something special on its hands that could help lead to a resurgence of investment in the Revolutionary War history in the Palmetto State and the South.

He just needed to find a way to tap into it.

“For there to be successful tourism and discovery of the history of a place, you need to be able to pull people off the interstate and tell the story where it happened, and then launch them out to the community,” Sheheen said. “That will help propel these preservation efforts.”

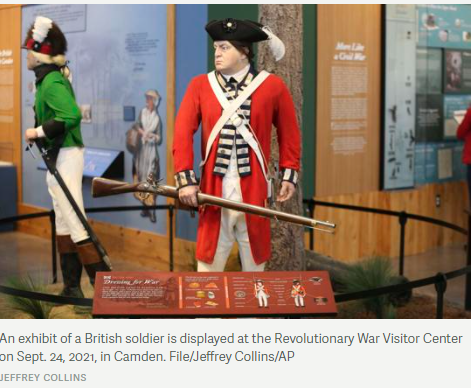

Working with state and federal partners, Sheheen and other backers eventually secured millions of dollars to help expand the site, erecting a museum and interpretive history center on the grounds of where the town stood, in what he hoped would become a “centerpiece” of a planned Liberty Trail snaking through significant Revolutionary War sites throughout the state. But there was still much to do.

In the Summer of 2019, Zemp was recruited to return to Camden to help reinvigorate the site after years of success within the Charleston preservation community. Taking cues from other historic sites around the country, Zemp sought to remake what Camden was, looking to turn it from a run- of-the-mill museum into an experience to immerse visitors into the period, similar to interactive sites like George Washington’s Mount Vernon or Virginia’s historic Jamestowne, outside of Williamsburg.

And they were well on their way, Briggs said, until her sudden death earlier this month.

Zemp’s funeral was Feb. 21, a final memorial to a figure who committed most of their life to preserving the legacy of the Palmetto State. But it’s the things she left behind, friends and colleagues say, that will reverberate through history.

In fewer than three years, Zemp not only infused new life into weary ground, but inspired others in the preservation community of the possibilities of what South Carolina’s revolutionary celebration could be, and established a template through Camden that other museums around the state could emulate.

Her ancestor may have founded Camden. But Ginny Zemp, colleagues say, brought it back to life.

“We’re only here because of her, that’s the truth,” Briggs said.

–postandcourier.com