ALABAMA: History of 1800s Black Baptists a story of Alabama’s post-Civil War rebirth

It was just 20 years after the first enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619 when the first Baptist church formed in Rhode Island.

Nearly 150 years would pass before the first Black Baptist church took shape in Savannah, Ga. in 1788.

In those years, “the North and the South joined heartily in the work of binding their (B)lack brother with the chains of cruel bondage … taken from his freedom and from his gods and chained to the chariot wheels of Christian civilization to be coerced, dragged into new observations, new experiences, and a new life,” Dr. Charles Octavius Boothe wrote in 1895.

Born in Mobile in 1845 and an ordained minister since 1868, Boothe’s seminal work, The Cyclopedia of Colored Baptists of Alabama, was first published 30 years after the Civil War.

The book not only served to document the history of Black Baptist churches in Alabama — Boothe traced its roots to Mobile’s St. Louis Street Missionary Baptist Church in 1836 — and their leaders.

The work also documented the rise of Black leaders in Alabama in the decades after Emancipation as the state neared the start of the 20th Century and the role they played in helping Black people across the state obtain educations and increase their economic power.

“From the days of my earliest recollection, freedom’s shadowy forms moved before the eyes of the Southern slave,” Boothe wrote.

“He felt or thought that he felt–he saw or thought he saw–the touch and visage of approaching liberty. In subdued tones it was whispered upon ears that could be trusted, that slavery, with all its accompanying horrors, was soon to be a thing of the past. Praying bands were organized and met in distant groves to pray for liberty.

“Gathered beneath the sighing trees and nightly skies, they whispered their agonies upon the ears of the Almighty–whispered lowly, lest the passing winds should bear their petitions to the ears of the overseer or master.”

Boothe wrote that for enslaved Black people “the war cloud bursts and the slave mingles his prayers with the roar of the booming cannon, tarrying on his knees while the American soldiery contend in mortal strife. It was understood to mean liberty. At last the deadly struggle ceased, and emancipation was declared. It was only the dawning, and therefore the light was dim.”

Boothe, however, wrote that with freedom came new struggles.

“The first view of liberty was frightful in proportion as it was seriously considered. Naturally, as the shackles suddenly fell off, there was such a forcible rebounding of life, as in many cases made liberty mean license to live idle and lewd.

“I can never forget my first impressions at the full view of freedom. O, what helplessness appeared in our condition!”

In 1864, near the end of the war and a year before the Emancipation Proclamation, Boothe that there were four Black Missionary Baptist Churches in Alabama, owning property worth about $10,000.

“The change which the war had wrought as to the civil status of the (B)lack man, changing him from slave to freedman, affected his church standing, so that ex-master and ex-slave did not quite fit each other in the old “meeting house,” as they had done in days of yore.

“There was restlessness on one side, and suspicion on the other. The (B)lack man wanted to go out and set up housekeeping for himself, while the white man in most cases feared and hesitated to lay on the hands of ordination. We did not know each other. The “negro preacher” on one side of the river had but little opportunity to know his brother on the other side. Truly our beginning was dark and chaotic.”

In the 30 years after the end of slavery, Boothe wrote that Black people were “beneath the opportunities and duties of free manhood, which is to say that for thirty years we have been associated with the family institution as husband, as wife, as parent, as sister, as brother, as son, and as daughter. Three decades with the family, developing affection and making patience.

“Thirty years of business life has passed upon us, which is to say that we have for this length of time been associated with those facts which grow out of our physical wants, such as labor, system, economy, competition, skill, etc.

“We have had thirty years over our own consciences, over our own wills, over our own church affairs. We have had thirty years with books and schools. We have had thirty years under the duties of citizenship. What have we attained to in this time? Have these years given us any fruits? Are we where we were in 1865?”

Boothe saw a great need for Black people in Alabama to harness their economic power.

“We earn millions of dollars, a large part of which we ought to and can keep among ourselves, and thus strengthen the financial standing,” he wrote. “We need to establish and maintain money operations among ourselves.”

“No moneyless people have any power or voice in the solid things of life,” he added. “We need plans of co-operation which will enable as to come together with our little savings until they aggregate to an amount that is large enough to support some sort of business. Saving societies or circles should be organized all over the country, for the purpose of studying methods for money saving and money investment.”

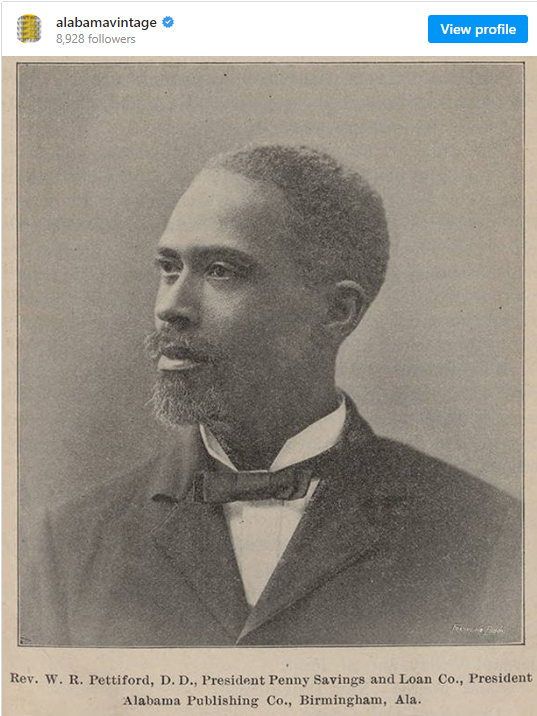

Boothe saw reason for hope in the creation on the Alabama Penny Savings Bank of Birmingham by the Rev. William Reuben Pettiford in 1890. It was the first Black-owned and Black-operated financial institution in Alabama.

“This bank gives the colored people of Birmingham a power in financial circles that they could obtain by no other means,” Boothe wrote.

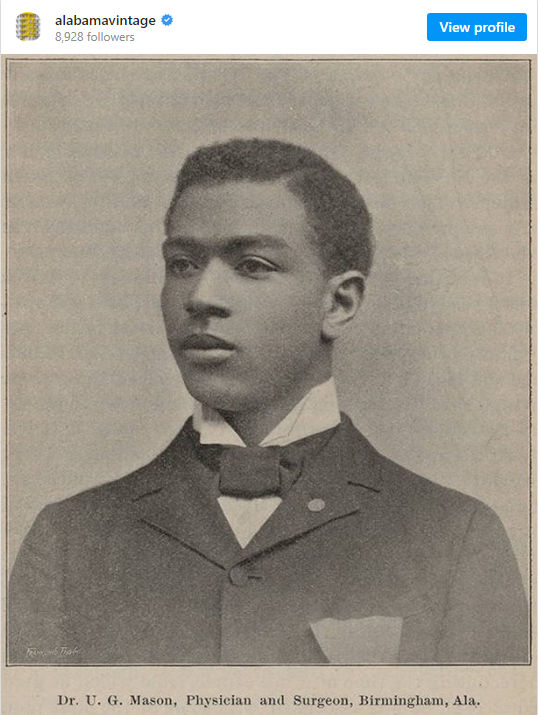

Still, Boothe saw a need for young Black people to find work beyond the menial occupations that often were the only ones available to them.

“The young (B)lack man–he returns to an empty void so far as concerns the business world. He comes home to be a loafer, or a boot-black, or a buggy boy, or a cook, or a waiter, or a barber, or a prisoner.

“He comes home to despair, to temptation, to ruin. And this sad state of things can never change by accident: … They say we can be preachers, teachers and doctors, but we can’t manage money and can’t unite in great business enterprises.”

Boothe wrote that he dared “to hope that there are better things in our hearts on this line than have yet appeared.”

Boothe’s book was reprinted in 1905 with updates about the churches and their leaders.

Having helped establish the Colored Baptist Missionary Convention of the State of Alabama in the early 1870s, Boothe retired in the early 1900s.

He died in Detroit in 1924.

–al.com

###