SOUTH CAROLINA: University Works to Digitize Black History Collection

COLUMBIA, S.C. — A hundred years ago, thousands of Black residents visited Washington Street for something modern Columbians take for granted — getting a photo taken.

There, they found the studio of Richard Samuel Roberts, whose side-job portraits captured a slice of Black Columbia in the 1920s and 30s, posed in front of painted backdrops and wearing everything from wedding dresses to work uniforms and sailor costumes.

Their likenesses were captured in the negative on glass plates, film’s technological predecessor, and eventually stored in a crawl space under the Roberts family home in the once predominately Black Wheeler Hill neighborhood.

They rested there for decades, until a University of South Carolina archivist worked with the family in the 1970s to pull the boxes out from below the house and preserve more than 3,000 glass plates in the university’s archives. About a tenth of the photos were published in 1986, in a book titled “A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts 1920-1936.”

But the majority of Roberts’ work has remained inaccessible to most — a point that’s being corrected inside USC’s special collections library, thanks to funding from the university’s Center for Civil Rights History and Research.

Digitizing the archives

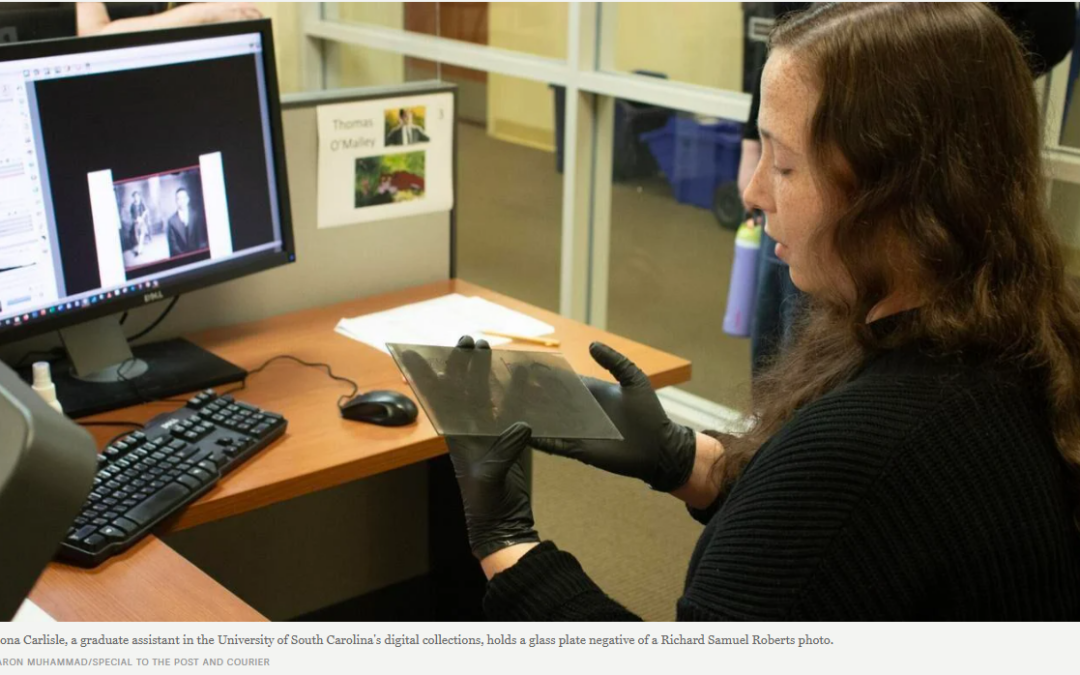

Inside the special collections office, graduate assistant Fiona Carlisle sits and painstakingly scans the negatives, using acid-free cardboard to shield the glass plates from scratches and plastic sheeting to stop the fragile negatives from sticking to the top of the scanner.

It’s a long process, one that may last around two years, but the scans will allow archivists to upload all of the Roberts collection to an online page where researchers and the public will be able to freely view and search through the photos. They’re being scanned in a high enough resolution to see the individual beads of a photo subject’s necklace.

“It would be a real shame if they weren’t seen by as broad an audience as possible,” Carlisle said.

‘A world of their own’

Roberts’ photos are a valuable historical source for understanding the capital city’s Black cultural, religious and educational history, particularly as there are few surviving photos of Black residents from that time, according to Bobby Donaldson, a USC history professor and executive director of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research.

“A lot of people think of the world of segregation and Jim Crow as this era of discrimination and oppression, as it was,” Donaldson said. “But I think these images also illustrate and remind us that in the midst of segregated and Jim Crow culture, African Americans were quite intentional in building a world of their own.

Roberts was also an artist, according to Beth Bilderback, a visual materials archivist at USC’s South Caroliniana Library.

He painted his own backdrops, and posed his sitters carefully to get the best light and capture their character. Even his “retro” choice to continue using glass plates instead of available film was an artistic choice of medium, Bilderback posited.

The photos portray a wide variety of subjects: Men, women, children, cats, dogs, deceased loved ones and even photos of photos meant to preserve already-historic images.

A portrait of a young Modjeska Simkins, the important South Carolina civil rights leader, is part of the collection, as are local athletes and workers. One frame captures a tiny baby sitting with an adult partly hidden behind the chair back, seemingly in an effort to keep the child to sit still for the camera.

In another, a cat poses for a portrait — with the next frame capturing only a blur and a paw as the feline leaps out of frame mid-shot.

As Carlisle works though the boxes of negatives, she sometimes comes across graphite marks on subjects’ faces from someone manually adding highlights to the photos. “It’s not just an Instagram thing, it’s an everytime thing,” she said.

Putting names to faces

Some of the images are on display at the civil rights center’s exhibit inside the Columbia Museum of Art, including window clings showing some of Roberts’ photos of children, part of an effort to identify the photos’ subjects.

The hope, Donaldson said, is that the exhibit and the digitalization process will help put the images in front of people who might recognize relatives or former neighbors, or even much younger images of themselves.

There’s already been some success on that front. Donaldson recounted recently visiting the museum gallery with a group of teachers, one of whom was able to identify her in-laws from a photograph of previously unnamed subjects in the “A True Likeness” book of Roberts’ work.

“These images enable us to reconstruct the landscape and geography of Columbia in ways we probably could not do otherwise,” he said.

–www.postandcourirer.com