SOUTH CAROLINA: How Archaeologists Dated Hilton Head’s Oldest Structure

HILTON HEAD ISLAND — A peculiar building sits beside a busy road on the eastern edge of Hilton Head Island. Its modern roof was built atop centuries-old walls. Its wide, open door frame and windows face Skull Creek, allowing a breeze to drift through the quiet interior.

The structure is made of traditional tabby — a mixture of lime, water, sand, oyster shells and ash. It’s a hardy, cement-like material that has stood through the American Revolution, Civil War and an onslaught of developers who marched across the island in recent decades.

Thomas Barnwell Jr. stands within his tabby on Hilton Head Island. The building, made of oyster shells, was built on the land long before it was purchased by Barnwell’s father in the 1930s.

Now called the Barnwell Tabby, archaeological researchers estimate it was constructed around 1765, making it Hilton Head Island’s oldest structure. The fact that it is still in the hands of a native islander adds to its rarity.

The tabby was a fixture of Thomas Barnwell Jr.’s childhood. Though, he admits, not one he found especially exciting.

He recalls cows sheltering within the four walls and grapevines growing along one side. His father, who purchased the property in the 1930s, would allow visitors to break off pieces of the ruin as a souvenir.

Barnwell inherited the land following his father’s death in the 1980s. As an adult, he found a new appreciation for the crumbling ruin. He set up a fence to deter vandals from breaking off pieces or climbing inside, and he pondered its history and future.

The 88-year-old began a renovation of the tabby in 2009. Though the structure was still prominent at that time, the roof and significant pieces of the walls were missing.

Hundreds of hours of work and $85,000 later, the Barnwell Tabby stood whole again in 2018. A new roof protects the interior, while tabby specialist Rick Wightman repaired missing pieces of the walls.

The Barnwell Tabby sits just east of Squire Pope Road. It is now believed to be the oldest structure on Hilton Head Island, constructed around 1760.

Barnwell wasn’t done. Soon after the renovation, he sought out sources and historians who could help him answer three lingering questions:

- Who really built the tabby?

- What was its purpose?

- And how could the building be used for education?

New findings and debunked legends

In the spring of 2019, an interior corner of the building was covered with a blackout tent to prevent any sunlight from shining through while a piece of the wall was painstakingly chipped away.

The sandy mixture of tabby was sent with other samples to the Utah State University Luminescence Laboratory. The lab’s use of a dating method called optically stimulated luminescence can seem like magic, said Kim Cavanagh, an associate professor of anthropology with the University of South Carolina Beaufort.

Kim Cavanagh is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of South Carolina Beaufort and a member of the research team looking into the history of Barnwell Tabby.

“It’s science,” she said, and it’s extraordinary.

The method is used to determine when a sample was last exposed to sunlight by counting the number of electrons within the quartz found in grains of sand. The findings helped the research team to estimate that the Barnwell Tabby was built in the late 18th century.

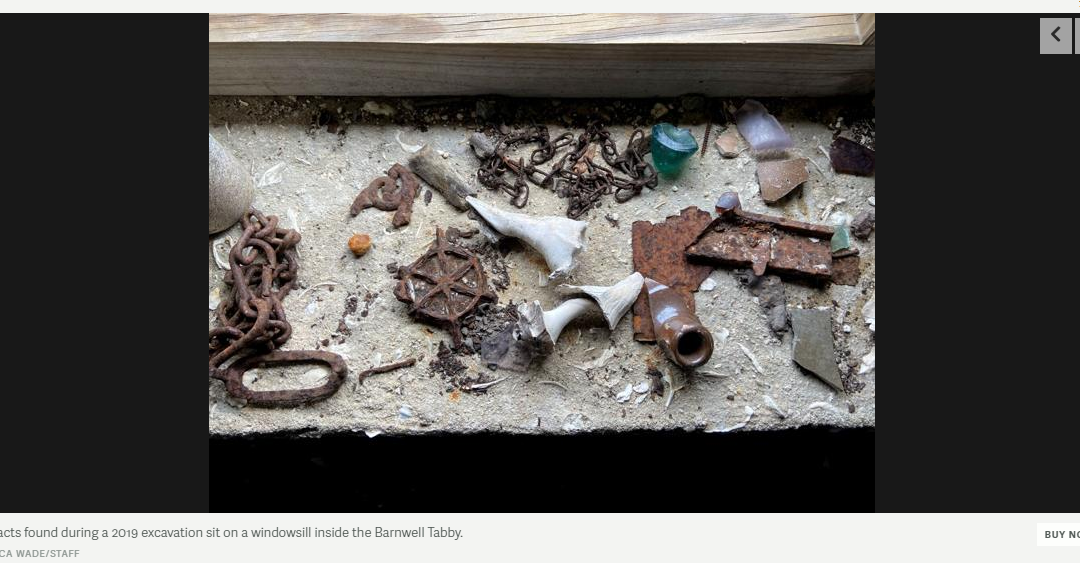

Archaeology students with the University of South Carolina Beaufort assisted with excavations of the site in 2019. They helped unearth hundreds of artifacts that were analyzed and, along with the results from Utah State University, helped the research team to place the construction of the tabby between 1760 and 1765.