SOUTH CAROLINA: Furman U researchers uncover 1,238 racially restrictive deeds connected to former board chairman

In the post-World War 2 era, Alester G. Furman Jr. was in charge of the family’s real estate business in Greenville.

A few years later, he served as chairman of the board at the university that bears his family’s name.

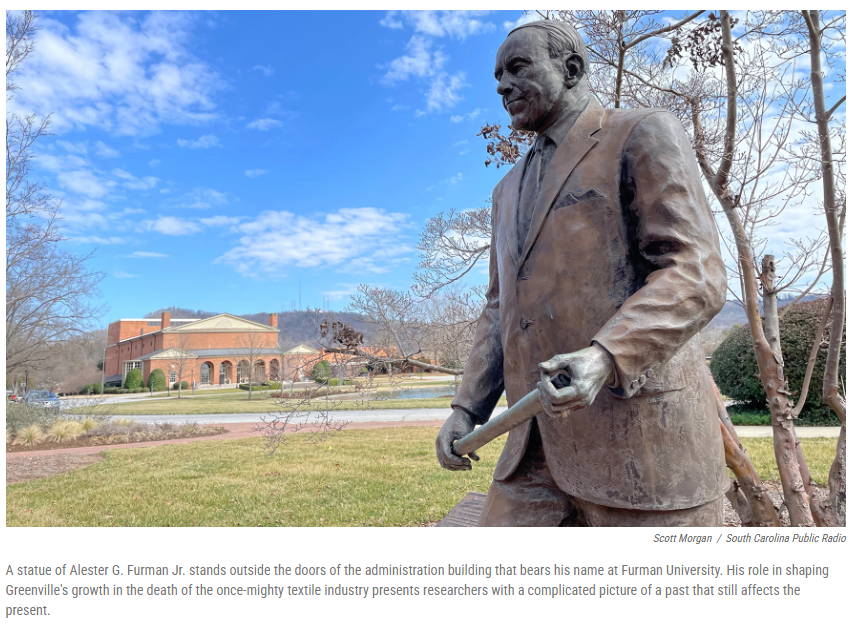

Later still, the university honored him by naming its administration building after him and erecting a statue of the man himself, striding purposefully toward the future.

“He’s a beloved figure,” said Ken Kolb, chairman of Furman University’s sociology department. “ We have a prestigious teaching award named after him. He helped provide the funds for the bell tower on our campus, which was one of our iconic features. Most importantly, he is largely credited with engineering the move of our campus from our previous downtown location to our current one.

“So when I found his name on documents with explicitly racist language,” Kolb said, “I didn’t quite know what to do.”

The documents Kolb mentioned are deeds of sale, to houses sold by dying textile mill companies to their workers when the industry that had built Greenville – and much of South Carolina – started to die in the 1930s and 40s.

The Furman Investment Co. brokered many of the sales, which is why Alester Furman Jr.’s name, as president and secretary of the company, is on 1,238 deeds that contain clauses to bar specific racial groups – mostly African-American – from buying particular properties.

For the record, although the Furman Co. still exists, it is no longer connected to the Furman family, and hasn’t been for several years.

Some of these deed covenants also forbade burial of Black residents in Graceland Cemetery, which abuts the Freetown community south and west of Greenville City. Freetown was one of the first communities in Greenville County where African-Americans could buy land and homes.

In 1918, Alester G. Furman Sr. became the president of Graceland Cemetery; Alester Jr. was named one of the cemetery’s directors.

‘We have to deal with it’

When Ken Kolb found the connection between racist deed covenants of the past – which have been illegal since 1948, but remain on the historic deeds to properties built when explicitly racial segregation was legal – he knew there were two things he could not do: ignore it or bury it.

“ These documents,” he said. “They’re all technically publicly available.”

That means that anyone willing to scour the past could – and Kolb was convinced someone eventually would – find the connection between the deeds, Alester Furman Jr., and the university. He worried that someone could easily drop the information on the world without context and would, in turn, ignite a fire that put the university in the middle of a racially centered controversy.

The university had already, just prior to the Covid pandemic, gotten out in front of its legacy connected to the school’s founder, Richard Furman, a major Baptist leader and thinker in the South in the 1800s. He was, initially, an opponent of slavery. Later, he became one of its largest defenders. His writings on slavery, in fact, served as core arguments in the South’s defense of it as an institution.

Kolb said getting ahead of what was bound to come out about Richard Furman allowed the community to learn of the university’s connection to a proponent of slavery and avoid the kind of trench warfare that comes with the discovery of such historical landmines that don’t always come with context.

So when it came time to tell the world about a more recent connection to racism, Kolb wanted to follow a similar path.

“We have to deal with it,” he said. “You can either sweep it under the rug, you can release it without context, or you can get together a group of scholars and try pull out the full context so that when you do give it to the public, that they can understand the good and the bad of it and they can make their own decisions.”

The questions

Alester Furman Jr.’s role in shaping Greenville as it is today was giant. Even if the 1,238 deed covenants Kolb and other researchers at Furman University found were the only thing taken into account, Alester Furman would have had a major impact on shaping the demographics of the city.

But, as Kolb mentioned, Furman had a leading hand in moving the university from its original downtown location to what is today Greenville’s suburbs.

And this, for Kolb, brings up a lot of questions: What does it mean when institutions, businesses, and households leave city centers for the suburbs? How did the university’s move, which coincided with the national trend of white flight from cities, create a hollowed-out downtown like Greenville became when its main economic engine disappeared? What are the implications today?

One neighborhood Kolb looked at was Judson Mill, one of the villages built by the mill to house workers and eventually sold to those workers, through deals made by Alester Furman Jr.

“ [Judson Mill] was an all-white neighborhood when it was rented out to mill workers and then it was embedded into the deeds to keep it all-white through racially restrictive covenants executed by the Furman Co.,” Kolb said. “It stayed all-white until the mill started to decline.”

In the 1970s and 80s, the mills were on their last legs in Greenville.

“[The city started] to lose the textile jobs to automation, to offshoring,” he said. “The area around Judson Mill is depopulating rapidly, and it’s losing its white population. But ironically, because the neighborhood was all-white, and contractually so through these racially restrictive covenants, when the white population decided to leave for the suburbs because the jobs were starting to decline, there was no one left.”

The long-reaching effect

The effect, Kolb said, was that the rapid depopulation of formerly all-white neighborhoods made those neighborhoods – which were originally sold on the promise of resilient, healthy futures – dilapidate much more quickly than mixed neighborhoods.

“So, having a diverse population actually makes a community more resilient to changes in the economy,” Kolb said. “Because you never know when one group might need to or want to leave to other areas. And this depopulation and decline in property values made it a prime target for real estate speculation post the Great Recession.”

Today, those formerly run-down neighborhoods, like Judson Mill, Nicholtown, and Bel-Aire, which had become overwhelmingly Black, are now some of the hottest locations in the upstate. And the ripple that’s creating is a kind of Black flight to the suburbs, where housing is less expensive than it is downtown.

But unlike white flight, which was predicated on the promise of better living and homeownership, lower-income residents are increasingly moving away from city services and jobs to rent homes where jobs are less-well-paying in neighborhoods not served by public transportation.

Furman University’s move to what was a large, open space coincided with the beginning of white flight. This could have accelerated the corrosion of downtown, or it could have just been a coincidence of timing, said Kelsey Hample, an economist at Furman University who worked on the deeds project.

“We didn’t have that data to turn to, to say we know exactly what was the cause and what was the consequence,” Hample said. “But absolutely, Furman’s move out into the suburbs coincided with a National Highway Act that allowed more people to move further away from urban centers. And it also matches exactly up with these big changes in demography. So, we weren’t able to say Furman caused it, or that Furman was part of that cause, but absolutely Furman is caught up in what’s going on.”

For Hample, the effect of Furman University moving to its current location went beyond college opportunity.

“At the time, Furman was not only a place of education, but a place to get employment,” she said. “And so one immediate effect of Furman leaving that downtown campus is that lots of people who used to be able to walk to their job at Furman University now are no longer able to walk to that job. As Furman left the downtown space, I would expect that there wasn’t immediately a replacement for those people to go get jobs in a similar line of work.”

And as far as the deed covenants, Hample said the long-reaching effects are evident in the disparities between white homeownership and Black homeownership.

“Maybe [racially restrictive covenants were] not federal policy or state policy, but it certainly was business practice,” she said. “That really creates inequality between two types of families. If you’re able to buy a house in this neighborhood that has increasing property values, by the time you pass that down to your children, that’s going to compound that inequity that is created early on. It’s really important to look at that and recognize that part of these decisions have lasting impacts in inequality.”

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, homeownership among African-Americans in the United States was 46% as of October, the latest data available. Black homeownership nationally, between 1994 and 2024, peaked in 2004, just shy of 50%.

Meanwhile, white homeownership in that same timeframe was lowest in 1994, at just shy of 70%. At the end of the third quarter of 2024, the rate wat above 74%.

When segregation was SOP

It needs to be stated that no one connected with Furman University’s deed covenant project is labeling anyone connected to those covenants a racist.

Rather, said Ken Kolb, 1,238 “pieces of paper” can only tell us about business transactions from an era in which segregation was part of the normal business environment.

“This was a complex time and these are human beings,” Kolb said. “This approach to understanding the effects of racialized real estate practices of the past doesn’t require individual mal intent. It doesn’t require personal prejudice or animosity towards a group. It was, at the time, standard operating procedure, whereby they were in the interest of selling property at the highest value.”

Those documents, whatever is written on them, Kolb said, don’t give researchers any insight into the hearts or minds of anyone buying, selling, or brokering any deals.

“We’re just looking at pieces of paper with racist language and looking at how they play out on maps,” he said. “And what’s the relationship between those practices of the past and the benefits to some neighborhoods, or the lack thereof, to others today?”

So as not to erase Black history

Part of the transition from mill villages to residential free market in Greenville involved Graceland Cemetery, for which Alester Furman Jr. served as one of the directors. The cemetery sits adjacent to Freetown, which is recognized as a historically Black community.

But Freetown didn’t have a cemetery of its own. And, just as residents “of African descent,” as many of those deed covenants put it, were not allowed to live in certain areas of Greenville, they also were not allowed to take their eternal rest there.

“The racially restrictive covenants pretty much said only white people in this area,” said Kaniqua Robinson, an applied cultural anthropologist at Furman University who is part of the deed covenants project. “And so, they had to find other places to be buried. So, it was not just a racial segregation of the living, but also the dead.”

Robinson said that her role in the deed covenants project centers on making sure aspects of African-American history in Greenville do not get swept aside.

“It’s important because the Black communities, their histories are being erased,” she said. “It’s actively being erased as gentrification continues.”

Robinson said that by speaking out and protecting Black history, “future generations can know about these communities, about Black people who thrive, who triumph, who are trailblazers here, despite the movement of people outside their homes, outside their community.”

So what was Alester Furman Jr. like?

Alester G. Furman Jr. received his bachelor’s degree (yes, from Furman University) before World War 1 began. He died in 1980 at the age of 85.

Not many people who knew him professionally are around today. His grandson, however, is.

Earle Furman worked for what then was still the family real estate business, but didn’t join the company until after his grandfather had retired. He still knew Alester Jr. as a sharp businessman.

“ He was especially good at negotiation, I am told,” Earle Furman said. “He knew what he needed to do to make something happen.”

Furman also knew his grandfather to be a proud man. Someone who knew Alester Jr. once told Earle that his grandfather “could strut while he was sitting down,” he said. “That’s got to tell you something.”

On a more personal level, Earle Furman remembers his grandfather as a warm man of many gifts.

“I loved him,” he said. “He had many, many talents, and he was very, very generous in many ways. In most of the ways, nobody knew about.”

Furman said his grandfather was generous with his time to most who would ask for it. He was also generous with his money – for example, he paid tuitions for people to go to college, from his own pocket. None of which was known at large.

And in his business, there is evidence that Alester Furman Jr. worked with Black families looking for housing in Greenville.

“We have evidence that the Furman Co. was interested in building communities, was interested in fostering homeownership, in a community where owner-occupied dwellings led to a more stable environment” Kolb said. “We have evidence that the Furman Co., under the leadership of Alester G. Furman Jr., financed some home loans for Black families who couldn’t get mortgages elsewhere; that the Furman Co. essentially helped develop and build a school near a mill in Piedmont.”

Could such actions be seen as PR? As a way to make the company look better by doing a few good things to polish the brand?

Sure, Kolb said. “But there’s no evidence of that. This is just evidence that they did some good things.”

In other words, he said, the past is nuanced, because the people who lived in it were complicated.

–southcarolinapublicradio.org