SOUTH CAROLINA: Columbia Offers Reconstruction-Era Tour

The following locations and people tell the story of the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era in Columbia SC. Curated with the assistance of Historic Columbia, each site or person offers connections to understand important events that shaped the period.

The Reconstruction Era spanned from 1865-1877 and marked the challenging post-Civil War period when the United States grappled with reintegrating the states that had seceded and determining the legal status of African Americans.

This era in Columbia SC was a time when the South Carolina State House was home to the first Black majority legislature, Black churches emerged as centers of community, social life and political power, Benedict College was founded and 90 percent of the students at the South Carolina College in 1870 – now the University of South Carolina – were Black.

Download the trail or pick up a copy at the Columbia SC Visitors Center.

STOP #1: MUSEUM OF THE RECONSTRUCTION ERA AT THE WOODROW WILSON FAMILY HOME

1705 Hampton Street

Photo Courtesy of Historic Columbia Collection

The parents of Thomas Woodrow Wilson, who later became the 28th President of the United States, had this former residence erected in 1871 as their family’s home while they lived in the capital city during the middle of the Reconstruction era. Today, the property, which is South Carolina’s only presidential site, also bears the distinction as being the nation’s first museum dedicated to exploring how Reconstruction shaped our contemporary nation.

As the Museum of the Reconstruction Era at the Woodrow Wilson Family Home, the destination affords visitors the opportunity to immerse themselves in panel exhibits, interactive technologies and guided tours that detail the advancements that the community made in the years following the Civil War.

African American leaders like Charles M. Wilder, one of the first African Americans appointed as postmaster and Richard T. Greener, the first Black graduate of Harvard and first Black faculty member of the University of South Carolina are highlighted throughout the museum. Exhibits also explore the changing meanings of citizenship and examine the importance and impact of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

The museum also explores the nationally publicized Ku Klux Klan trials of 1870 and 1871. A few members of the KKK worked to prevent Blacks from voting and conspired to threaten and intimidate them during the election of 1870. Prior to this case, violence against Blacks would be handled at the local and state level, but since this violence was used to prevent voting, this violated federal law and became an opportunity for the federal government to underscore what lengths they could go if one tried to prevent civil liberties.

STOP #2: BENEDICT COLLEGE

1600 Harden Street

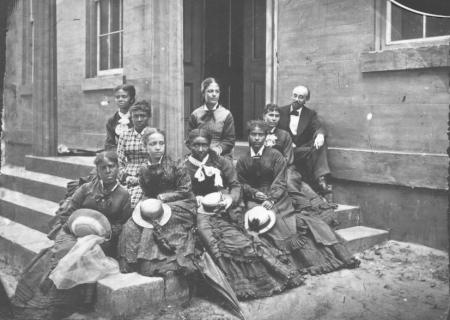

Founded in 1870, Benedict College embodies one of the Reconstruction-era’s most significant achievements — equitable access to education for people of color. Rhode Island philanthropists Stephen and Bathsheba Benedict established the campus of Benedict Institute on former plantation land so newly freed people and their descendants could benefit from educational opportunities previously enjoyed by only white students. Benedict College’s Historic District—listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1987—includes Morgan Hall, the school’s oldest remaining building, built in 1895. Today, Benedict offers 25 degree programs to more than 2,000 students seeking an HBCU education.

Photo Courtesy of Historic Columbia Collection

STOP #3: RECONSTRUCTION CHURCHES

819 Woodrow Street, 1401 Pine Street, 801 Washington Street, & 1720 Sumter Street

Photo Courtesy of the John H. McCray Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.

During the Reconstruction era many of Columbia’s Black churches began, not only as places of worship independent from white churches, but as centers critical to building community, social life, and political power in the years after the Civil War.

Bethel AME Church, First Calvary Church, Zion Baptist Church and Ladson Presbyterian Church all were established during Reconstruction, and several other community churches were key gathering places during this era as well.

While Bethel AME Church was established outright in 1866, the other three grew from existing congregrations with an intention to better serve the Black community.

First Cavalry Church and Zion Baptist Church stemmed from the Baptist Church (today’s First Baptist Church), under the leadership of Samuel H. Johnson and Frank Dobbins, respectively.

Ladson Presbyterian Church was established in 1874 after severing its ties with First Presbyterian. The church selected its first Black pastor, Mack Johnson, in 1876. Though the structures from the Reconstruction era are no longer standing, the present church was built in 1896 and the congregatiion there led by Pastor Mack Johnson until his death in 1921.

There are several other churches in Columbia with antebellum roots, and you can learn about them at Historic Columbia’s website.

STOP #4: PHOENIX BUILDING

1625 Main Street

The home of the influential and hyper-partisan newspaper, The Daily Phoenix, still stands today at 1625 Main Street. The paper first appeared just weeks after the burning of Columbia decimated about a third of the city in 1865. With this building completed in 1866, Phoenix owner and publisher Julian Selby continued to use his paper to amplify the voices of newly disempowered Democrats seeking to reinstate some semblance of their antebellum past. Selby indulged Democrats’ stories about the false “Lost Cause” narrative. Many of these published stories, though biased and even misleading, shaped the general public’s view of the Civil War and Reconstruction for generations.

STOP #5: SOUTH CAROLINA STATE HOUSE

1100 Gervais Street

Top Photo Courtesy of Historic Columbia Collection

Bottom Photo Courtesy of Sean Rayford

The State House opened in 1869, but the building project began in the 1850s with plans to include celebrations of slave society (with sculptures that depicted enslaved African Americans laboring in cotton and rice fields). Reconstruction-era South Carolina legislators prioritized salvaging the structure that had been left uncompleted and without a roof throughout the Civil War.

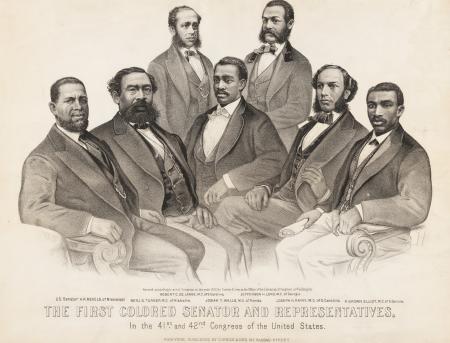

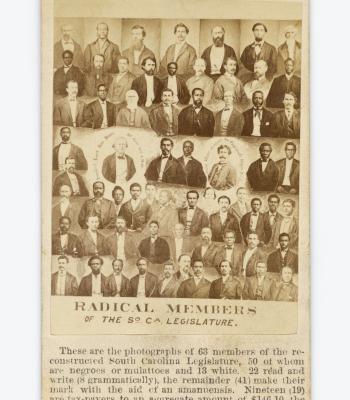

In 1868, South Carolina’s first Black majority state legislature was elected. Of the 124 members of the South Carolina House of Representatives, 75 were Black, and 10 of the 31 members of the State Senate were Black as well. This Republican legislature was the first to occupy the State House that stands today. South Carolina was the only state in the U.S. to elect a Black-majority legislature, and it did so four times in a row, from 1868 until 1874.

The assemblies of 1868 – 1874 had a progressive vision for South Carolina and appropriated funds for public schools, purchased land for public works programs, and prioritized reform programs for the State Hospital and the South Carolina Penitentiary.

Reconstruction ended after Wade Hampton III, a Confederate general and Democrat, was elected Governor of South Carolina in 1876 through broad intimidation efforts. This, coupled with the Compromise of 1877 (the withdrawal of federal troops from the South), concluded the Reconstruction period and gave way to the Jim Crow era that largely stayed in place until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

STOP #6: UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Downtown Columbia

Originally known as South Carolina College, the institution was forced to close between 1861 and 1865 as the Civil War disrupted so many aspects of life in the South. With the onset of the Reconstruction movement and new leadership at the state level, South Carolina College reopened as the University of South Carolina in 1866 and became the only state-supported college in the South that included African Americans on its board (in 1868) and admitted African American students (1873). In fact, by 1875, nearly 90 percent of South Carolina College’s students were Black, although classes were still segregrated.

During this time, the university’s first African American professor, Richard T. Greener, lived at Lieber College and served as a librarian across the Horseshoe at the college’s library building. This structure, built in 1840 as the nation’s first freestanding library, is known today as South Caroliniana Library. Greener went on to serve as the Dean of the Howard University School of Law and as an international diplomat during the William McKinley administration. Visitors to Thomas Cooper Library can now see a nine-foot statue of Greener, dedicated in 2018.

Following the end of Reconstruction in 1877, Governor Wade Hampton III ordered that the biracial university be closed. It reopened in 1880 as an all-white agricultural college. African American students were not admitted again until 1963, when a judge ordered the university to desegregate. On September 11, 1963, Henrie D. Monteith, Robert Anderson, and James Solomon began their studies.

Top Photo Courtesy of University of South Carolina Archives

STOP #7: HAMPTON-PRESTON MANSION & GARDENS

1615 Blanding Street

Photos Courtesy of Historic Columbia Collection

Located in the Robert Mills Historic District, the Hampton-Preston Mansion & Gardens is most commonly associated with the socially elite and politically powerful antebellum planter-class families that owned it from 1823 until 1873. However, during the Reconstruction era, the four-acre urban estate served briefly as the official residence of Republican Governor Franklin J. Moses. His frequent parties drew national attention for challenging South Carolina’s long-held racial and class boundaries.

White southern Democrats who resented the empowerment of Black men and the state’s integrated legislature ultimately held up some of Moses’ corrupt dealings, including the purchase of this mansion, as examples of widespread Republican corruption. Resentment on the part of many white South Carolinians over perceived Republican-backed corruption fueled the election of Wade Hampton III—a Hampton family descendant and former Confederate general—as governor in 1876. Shortly after the so-called “Redeemer” governor assumed office, the Reconstruction era ended as federal troops withdrew from the South in 1877.

Today, this publicly accessible historic site features exhibits and digital resources that emphasize the stories of enslaved men, women, and children and their planter-class owners during the antebellum period and of emancipated Black people who worked at the site during the Reconstruction era.

Also explored are the ways in which the Hampton-Preston family and its contemporaries—especially diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut—contributed to the Lost Cause, a movement begun during the Reconstruction era that memorialized the Confederacy and its soldiers as noble and just.The wife of a wealthy planter, United States senator, and Confederate general, Chesnut kept journals full of notes on daily life during the Civil War from 1861 to 1865. Heavily revised over many years and posthumously published as A Diary from Dixie, Chesnut’s work became an important piece of Lost Cause literature that continues to influence the public’s understanding of the war and its causes to this day.

STOP #8: RANDOLPH CEMETERY

Western Terminus of Elmwood Avenue

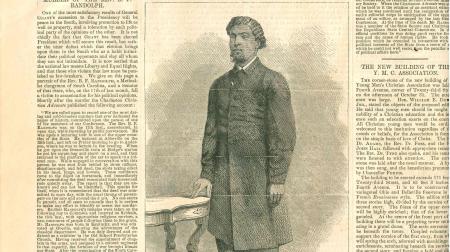

Reverend Benjamin F. Randolph played a significant role in the 1868 South Carolina State Constitutional Convention, where he successfully promoted universal public education for all. He then briefly served as a Republican state senator before being assassinated in October 1868 by a group of armed white men. In 1871, 19 local Black legislators and businessmen purchased land and established this cemetery as a more dignified final resting place for African Americans in Columbia. They named it for Randolph, who was reinterred under the monument dedicated to him. Eight other Reconstruction-era legislators are also buried here along with other figures of the Civil Rights movement.

Photo Courtesy of Historic Columbia Collection

TRAILBLAZERS OF THE RECONSTRUCTION ERA

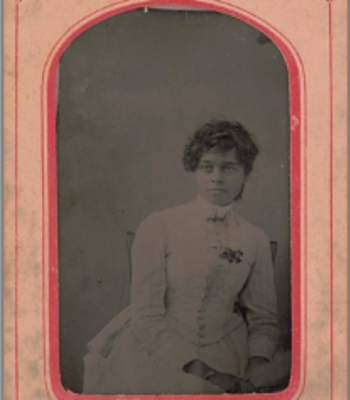

Clarissa Minnie Thompson Allen (1859-1941)

Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Clarissa Minnie Thompson was one of nine children born to Eliza and Samuel B. Thompson, who were enslaved on a plantation that is today part of the BullStreet District. Her father served as a delegate to the 1868 Constitutional Convention and then as a Reconstruction era legislator. Thompson was one of a few women who attended the South Carolina State Normal School during Reconstruction, when it was housed on the campus of the University of South Carolina. After graduation she taught at Howard School in Columbia and later joined the faculty of Allen University when it relocated to Columbia. In the 1880s, she published a series of stories about “Capitola,” a fictionalized version of Columbia, in The Boston Advocate. Had these stories, collectively known as Treading the Winepress, been published in novel form, it would have been only the second novel published by a black woman in the United States. She moved to Texas soon after, where she taught and published additional work until her death.

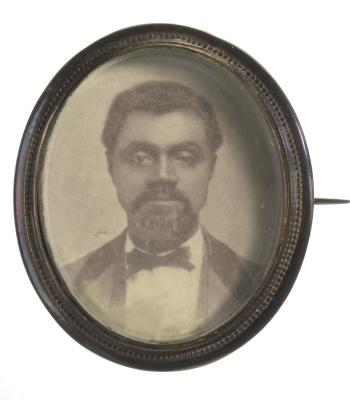

William Beverly Nash (1822-1888)

Photo Courtesy of the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Family of William Beverly Nash

Brought to Columbia by his enslaver, William Campbell Preston, a president of South Carolina College, William Beverly Nash made his mark on the city (and state) during Reconstruction. A Virginian by birth, Nash represented Richland County in the 1868 South Carolina State Constitutional Convention and served in the state senate as a Republican from 1868 until 1877. Nash advocated for a universal male suffrage plan that would not have property or literacy requirements at the National Freedmen’s Convention in 1867 in Washington, D.C. He is buried at Randolph Cemetery.

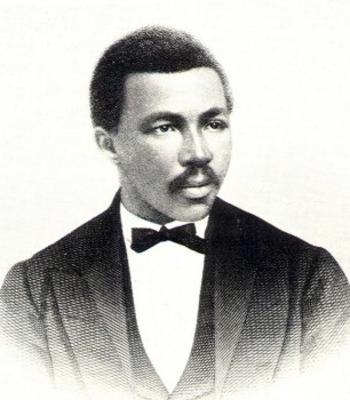

Robert Brown Elliot (1842-1884)

Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Born in England, Robert Brown Elliott moved to the United States shortly after the Civil War and quickly dove into Reconstruction era politics in South Carolina. Known as an excellent public speaker, Elliott advocated for public education and helped strike down requirements for poll taxes and literacy tests for voters. Appointed as the assistant adjutant general of South Carolina in 1870, he had the authority to use the state militia to protect Black citizens from the Ku Klux Klan. Elliott was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Republican after a contentious election in 1870 to represent a district that included Columbia.

Elliott was relentless in his pursuit for comprehensive civil rights. He spoke passionately against the Amnesty Bill, which ultimately prevailed and re-established political rights to nearly all former Confederates. But he was somewhat successful in weakening the Ku Klux Klan with a bill that reinforced the voting rights of freed men; this paved the way for the Ku Klux Klan trials in Columbia.

During his second term in Congress, Elliott partnered with Senator Charles Sumner’s Civil Rights Bill, seeking to eliminate discrimination from public transportation, schools, and more.

Elliott couldn’t help but see the weakening of the Republican Party in South Carolina and thus the continued endangerment of Black politicians. It is for this reason he resigned from Congress and then was elected in the South Carolina general assembly. He was the state’s attorney general in 1876 when South Carolina’s Reconstruction government collapsed and was forced out of office in 1877. He worked in a variety of government positions but died in poverty in 1884.

Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Henry E. Hayne (Born 1840)

Photo Courtesy Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Henry E. Hayne was the nephew of a prominent antebellum politician, and the son of a white father and a free Black woman. He represented Marion County in the 1868 South Carolina State Constitutional Convention and served as the South Carolina Secretary of State from 1872 until 1877. By registering as a medical student at the University of South Carolina in 1873, Hayne led the first racial integration of the University of South Carolina.

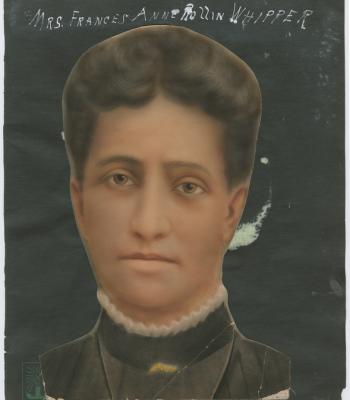

The Rollin Sisters