VIRGINIA: Virginia Museum of Fine Art Revels in Black Culture

Did somebody say “Cheese Trail?” Well, I’m here for it. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and urban design columnist for the Los Angeles Times, and I’m here with the week’s essential arts news and more art reports cultivated during my cross-country drive — because what’s the point of writing a newsletter if you can’t foist your vacation photos on everyone?

‘Dirty South’ is revelatory

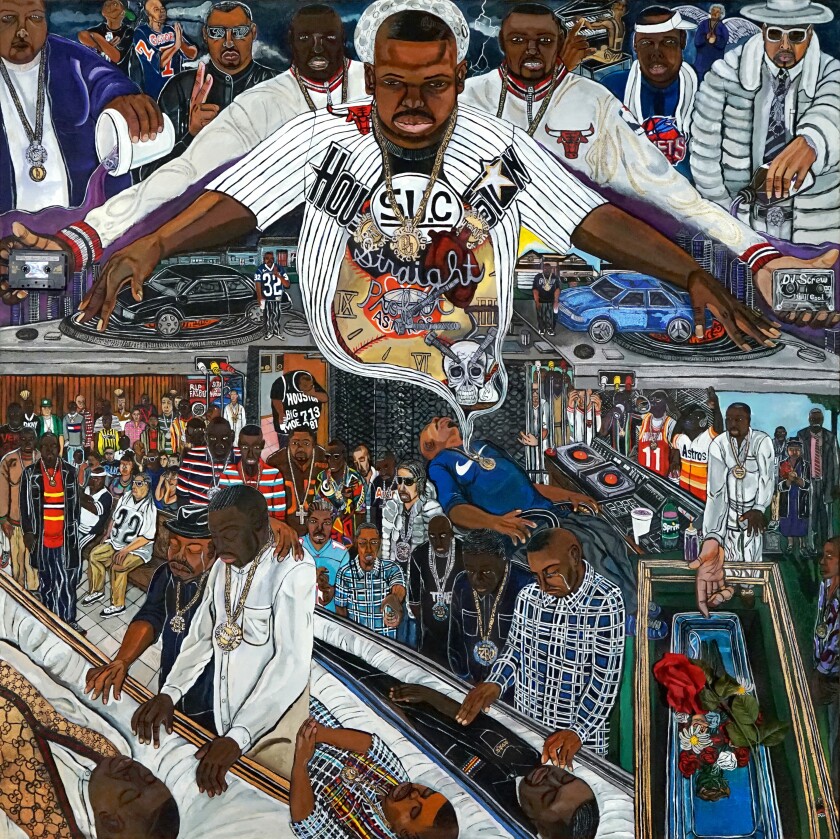

Is it too early, in the month of August, to start compiling one of those year-end “best” lists? No, you say? Well, good. Because No. 1 on my working list at the moment is a powerful and engrossing group show in Richmond, Va. “The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse,” on view at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts through early September, is a tour de force. Or, more accurately, a tour de South. And it will leave you wanting more.

Organized by the VMFA’s curator of modern and contemporary art, Valerie Cassel Oliver, the exhibition charts the ways in which Black artists have drawn from Southern tradition in the creation of art, music, design and the countless hybrid spaces in between.

It’s a show about the art that has emerged from a region that is also about so much more. It’s a show about the ways in which different forms have reacted and engaged with one another — how landscape materializes in art, how Black bodies materialize in those landscapes, how spirituality materializes in culture, how music permeates it all and how all of it has informed American culture.

The exhibition goes back a century — with works, such as a watercolor by Aaron Douglas, that date to the 1920s — drawing from the region’s rich cultural history. This includes folk art, vernacular architecture and music. The point, says Cassel Oliver, is to look at art “not necessarily through a Western sensibility, but a Southern sensibility.”

This includes, for example, a three-dimensional geometric wall piece by contemporary artist Sanford Biggers that employs an antique quilt as its source material. (Biggers is currently the subject of a solo exhibition at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, where he is displaying work from that series.)

And, in fact, “Dirty South” feels more like intense journey than run-of-the-mill museum exhibition. And that journey begins in the lobby of the museum, which features a SLAB — that’s Houston parlance for a lowrider, standing for “Slow, Loud and Bangin’” — a tricked-out Cadillac bearing the license plate “DRTYSTH,” created by hip-hop artist Richard “Fiend” Jones. Get in, it seems to say. You are going on a ride.

Functioning as the exhibition’s principal wayfinders are three sound and video installations that provide visceral jolt and serve as a framework for all of the other work in between. This includes a large-scale installation at the entrance by Paul Stephen Benjamin titled “Summer Breeze” that features a stack of TV monitors playing fragments of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” spliced with Jill Scott‘s 2015 rendition of the song. The phrase “black bodies swingin’” is endlessly looped and juxtaposed against a visual loop of a little Black girl rocking back and forth in a swing — Black joy and Black pain inextricably intertwined.

At about the show’s midpoint comes Nadine Robinson’s “Coronation Theme: Organon,” from 2008, which features a stack of amplifiers arranged in a way that evokes the Gothic profile of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where Martin Luther King Jr. once served as a pastor. From it emerges a sonic work that fuses elements of George Frideric Handel’s “Coronation Theme” with “notes” that are crafted from the sound of fire hoses and barking dogs. It is a magnetic combination of the wretched and the angelic.

The exhibition closes with Arthur Jafa’s searing video “Love is the Message, The Message is Death,” which drew widespread acclaim when numerous museums streamed it online last year in the wake of the uprisings. The video, set to Kanye West’s rousing “Ultralight Beam,” weaves together strips of found footage to articulate the traumas and the exhilaration of the Black experience in the U.S. — as if all of the content from the 200-plus pages of Toni Morrison’s “The Black Book” had been compressed into seven minutes of lived experience.

I first saw Jafa’s piece in a group show called “Prisoner of Love” at the MCA Chicago in 2019. I watched it again when it briefly landed online last year. Like many people, I was left stunned by it — grappling with the emotional and historical enormity he manages to deliver with such concision.

Since the piece began to gain a widespread following last year, the artist has expressed a certain wariness about how it is being received. “He himself has had a lot of trepidation about that work because it’s almost a spectacle of pain,” says Cassel Oliver. “Yes there is pain. But there is pleasure. There is an ecstatic that comes out of the spiritual, and the ecstatic that comes out of sex.”

In the context of “The Dirty South,” however, “Love is the Message” is informed by every object that comes before it: the ebullient depiction of a revival meeting, the folk art that infused Modernism, the painting of a blackened nighttime landscape illuminated by a constellation of lightning bugs, the generational struggles of Black people in the United States. In that setting, Jafa’s video feels less like a surprising blow and more like a logical conclusion, in all its terror and its sublimity.

“Dirty South” is a journey. The viewer who goes in will not be the same one who emerges.

“The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse,” is on view at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts through Sept. 6.; find additional information at vmfa.museum. The show is also scheduled to open at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston in the fall, after which it will travel to Crystal Bridges in Arkansas and the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver in Colorado. Do not miss.