TEXAS — San Antonio Set To Host First Mexican American Civil Rights Museum

San Antonio is inching closer to becoming the site of the nation’s first Mexican American civil rights history museum.

Why it matters: Museums serve as vital spaces where people see reflections of themselves, their culture, their ancestors’ struggles and the contributions of their community, yet Mexicans and Latinos overall remain underrepresented among the nation’s estimated 33,000 museums.

- “If people don’t understand your contributions, then they only see your deficits. They only understand the negatives, and you’re defined not by your contributions and by your positives, but instead by your stereotypes,” U.S. Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-San Antonio) said during a press conference on Friday.

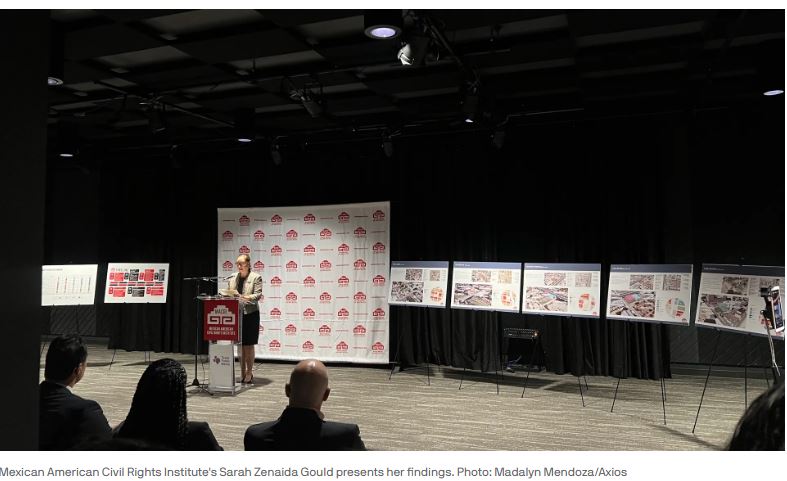

The latest: The Mexican American Civil Rights Institute (MACRI) partnered with Ford, Powell & Carson, a local architecture firm, to conduct a 10-month site feasibility study.

- On Friday, they unveiled potential locations for a trailblazing museum.

What they did: They identified lots and buildings that are either vacant or available for purchase across five districts, which the firm labeled Village, Gateway, Institutional, Cultural and Creekside. These areas are centered on a stretch of Commerce Street from Colorado Street on the West Side to Milam Park in downtown.

- Village is near the MACRI visitor center, Gateway is closer to Alazan Creek, Institutional is near the University of Texas at San Antonio and Interstate 35, Cultural is near Milam Park and Creekside neighbors Texas Public Radio.

Zoom in: All of the locations are connected to the settlement patterns of Mexican Americans as the city grew, MACRI executive director Sarah Zenaida Gould tells Axios.

- For example, a former bank building in the Cultural district sits in a historically significant area that was once part of Barrio Laredito, a neighborhood bulldozed during the construction of Interstate 10 in the 1960s.

- It’s also near the original site of La Prensa (1913), a Spanish daily newspaper, and the Alameda Theater (1949), which showcased films from the golden age of Mexican cinema.

Zoom out: The 2016 opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian triggered a surge in African American heritage tourism, resulting in a multimillion-dollar industry.

- Gould believes San Antonio — with its rich history and notable sites such as the Missions — is well-positioned to lead the rise of Latino heritage tourism.

- Although the Mexican American Museum of Texas is planned for Dallas, MACRI’s project will focus on civil rights from a national perspective.

By the numbers: The museum’s projected cost ranges from $15 million to $20 million. It will span approximately 20,000 square feet, which Gould considers a midsize facility.

- The money will come from public and private sources

Between the lines: Gould attributes the delay in establishing such a museum to a lack of funding and limited scholarly representation.- “It has taken a long time to build a pipeline of scholars who focus on Mexican American civil rights history,” she says, noting that exhibits rely on their research.

What they’re saying: “It’s going to be an opportunity for learners of all ages to know these powerful stories that generally are not taught in school, to find inspiration in those stories and to recognize how we all have a role to play in our shared democracy,” Gould says.

- “(The museum) belongs in San Antonio. It is our story. And the children and grandchildren who inherit the city will inherit those stories but also inherit its mission,” San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg said during the press conference.

What’s next: The site selection process will take six to nine months, followed by a design phase and capital campaign. The completion date has not been finalized.

- Gould promises it will cover pivotal moments such as the Chicano Movement, as well as provide a comprehensive view of earlier civil rights history.

- “We just want to make sure that people know that this didn’t just come out of nowhere, that our communities have been concerned about our standing in the United States for many generations, and that we have never just allowed ourselves to be marginalized, that we’ve always stood up for our rights,” she says.