SOUTH CAROLINA: Archaeologists Search for Wreck of Early American Ship Near Georgetown

GEORGETOWN — A team of underwater archaeologists is on the hunt for a Spanish shipwreck from the 1500s that could unlock more secrets about one of the earliest European settlements in the continental United States.

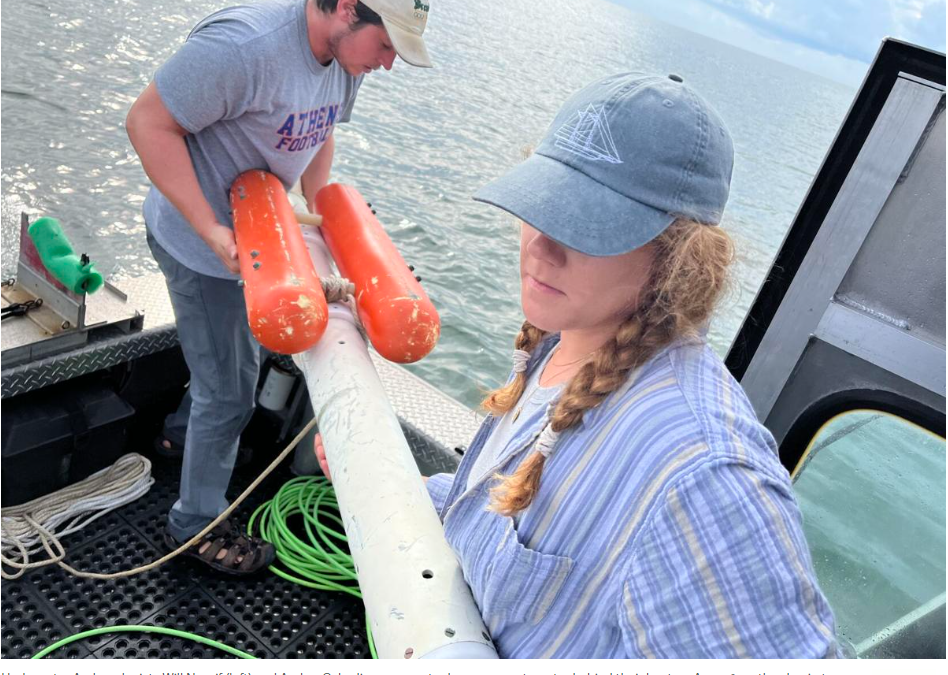

An hour after the break of dawn, around 7:45 a.m. Aug. 26, Amber Cabading, Athena Van Overschelde and Will Nassif pulled their boat away from the South Island Public Boat Landing.

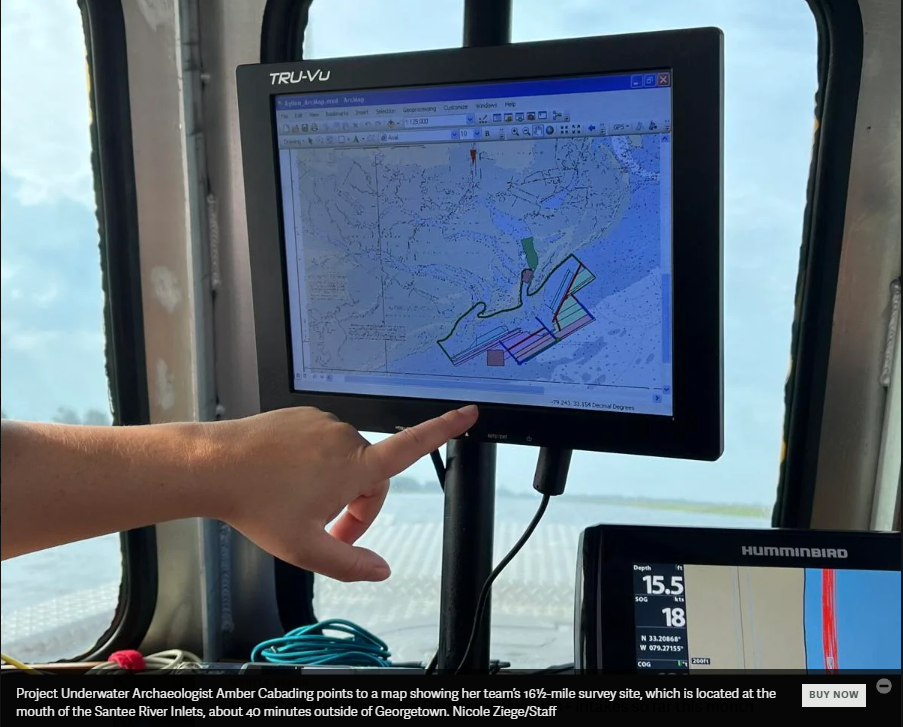

The trio from the S.C. Institute for Archaeology and Anthropology was sailing 40 minutes south to a 16½-mile stretch of marsh and open water located at the mouth of the Santee River Inlets.

The site is believed to be the location of the “Capitana,” a shipwreck from the 1526 expedition of Spanish explorer Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.

“It’s one of the first recorded shipwrecks in the Americas,” Cabading, 28, said. “It gives us a little snapshot of what the colonizers were in their mindset. What was their life like? Who was on board? How did they live on board? All of that can kind of be teased out if we find whatever is left of it.”

In 1526, Ayllón departed the Caribbean to colonize the Atlantic coastline of the modern United States. His fleet consisted of six vessels that carried over 600 colonists and many supplies meant to help in creating a new Spanish settlement.

“Capitana” was the largest of the fleet, and it sank along the coast of what is now South Carolina, at the mouth of a river that Ayllón called the “Río Jordán.” Over the past three decades, modern scholars have debated on the location of this river.

Many archaeological surveys have tried to locate the flagship based on the conclusions of historian Dr. Paul Hoffman, who suggested that the “Río Jordán” is either Winyah Bay or the North and South Santee rivers. Previous surveys have also focused on coastal inspections and remote sensing at the entrance to Winyah Bay.

For the S.C. Institute for Archaeology and Anthropology, this is not the first time officials have conducted a survey in search of the lost flagship. In 1991, the Institute led a coastal survey of beaches along the Winyah Bay-Santee areas. However, no 16th century cultural material was found.

Since then, the institute has reexamined Dr. Hoffman’s theory and reviewed other supporting historical documents, which ultimately suggest that the missing ship was lost near the entrances to the Santee River.

State Underwater Archaeologist James Spirek, a leader of the project, said the shipwreck could also help point archaeologists toward the location of San Miguel de Guadalupe.

In 1526, after a month of salvaging the “Capitana” shipwreck, Ayllón sailed south and founded San Miguel de Guadalupe. Although this colony was eventually abandoned after a six-week occupation, it was one of the earliest European settlements in the continental United States.

“Discovering this significant early Colonial shipwreck would prove of great scholarly and general interest of this fascinating period in the development of the United States and the New World,” Spirek said in a statement.

For more than a month in total, the team has covered different sections of the site each day. While driving at about 10 mph, they utilize the boat’s sonar and magnetometer — two instruments commonly used in surveying for shipwrecks. Sonar uses sound waves to “see” in the water, and a magnetometer measures changes in the Earth’s magnetic field.

Through these tools, the trio hopes to pick up any noticeable changes beneath the water — like unusual shapes or traces of iron and phosphorus material that could lead them to a possible shipwreck.

Once the team has covered the water, they will develop a report of their findings from the water portion of the site. Then, they plan to use a drone to survey the adjacent beaches and marshes within the site.

The drone portion of the project is expected to start early next year.

The project has been funded by a 2021-22 fiscal year legislative earmark worth $250,000. The funding was sponsored by state Sen. Stephen Goldfinch, R-Georgetown, and administered through the S.C. Department of Archives and History.

Van Overschelde, 31, said the team has faced several challenges with surveying the water portion of the site. For example, they cannot drive the boat through depths of less than 5 feet, and they are constrained by the timing of high tide and low tide.

High tide often starts in the early morning, and low tide causes more shallow water in areas closer to the marshes. This makes it more difficult for the team to survey the water with their magnetometer, which follows behind the back of the boat in the water.

Also, they have had to end some days early because of difficult weather developing in the afternoons.

Then, if they notice anything unusual, the team would need to dive beneath the water. However, diving requires the team to be constrained by their limited amount of oxygen.

“The water just adds an extra layer to every aspect of the aggregation and the search for the sites,” Van Overschelde said. “It just makes it more complicated.”

The team isn’t letting these challenges hinder them from the hope of finding this missing flagship. Van Overschelde, for example, said she grew up on tales of pirate ships and treasure hunting, and she is staying optimistic.

“I’ve never been on a project of that scale where we actually find what we’re looking for,” Van Overschelde said. “It would be pretty amazing.”