In 2018, the Palmetto Society invited me to deliver a speech at White Point Garden to commemorate the 242nd anniversary of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, which took place on the 28th of June, 1776. For this year’s celebration of that historic day, long known as Carolina Day, I’d like to share the text of that speech in the hopes that people unfamiliar with the event might draw inspiration from the bravery and determination of those who fought for our nation’s independence.

Carolina Day

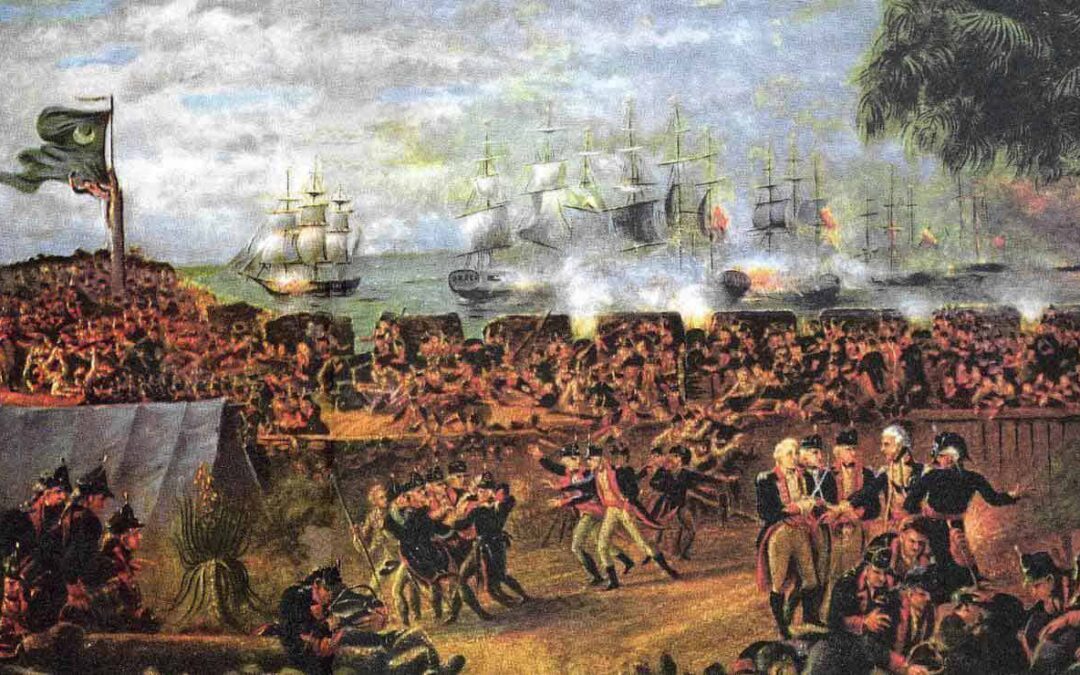

We are gathered here today to commemorate the anniversary of an important military victory that took place in 1776, the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, in which a small but courageous body of men repulsed an attack launched by the most powerful military on the planet.

We come here each June 28th to perpetuate the memory of their triumph and to acknowledge their sacrifice. We stand here in the blazing sun, just as they did 247 years ago today, to revel in the long shadow of their distant memory.

The Battle of Sullivan’s Island wasn’t the first battle of the American Revolution, of course. It wasn’t even the first exchange of gunfire between American and British forces in South Carolina. It was, however, the first clear and indisputable American victory in our war for independence, and the significance of that fact reverberated from Sullivan’s Island to Independence Hall in Philadelphia, to the houses of Parliament in London, and even to the court of Louis XVI at Versailles. It demonstrated to the world that raw American troops, composed of farmers, shopkeepers, tradesmen, merchants, planters, immigrants, and enslaved Africans, were resolutely determined to stand their ground and to defend their dreams of liberty.

Most of you here today know the story of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island inside and out, so what can I say that might be new or different from other commentators on the same subject? This certainly is not the time or the place to attempt to recount every detail of the battle or to commemorate every act of bravery and sacrifice. Rather, I’d like to try to increase your appreciation for the significance of this battle with a few remarks about the general context.

Most of you here today know the story of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island inside and out, so what can I say that might be new or different from other commentators on the same subject? This certainly is not the time or the place to attempt to recount every detail of the battle or to commemorate every act of bravery and sacrifice. Rather, I’d like to try to increase your appreciation for the significance of this battle with a few remarks about the general context.

The Battle of Sullivan’s Island took place just fourteen months after the first acts of open rebellion in South Carolina in April of 1775. It was fought by raw troops drawn from South Carolina’s provincial army, which was created just twelve months before the battle commenced. This major battle, the largest of its kind in South Carolina’s century-long history, took place just four months after this state tentatively declared its independence and adopted a state constitution in late March of 1776. The 28th of June 1776 was also the day that Thomas Jefferson presented the first draft of the Declaration of Independence to our Continental Congress, declaring the thirteen separate British colonies were henceforth to be known collectively as the sovereign United States of America.

The Battle of Sullivan’s Island took place on a single day, commencing at eleven a.m. and concluding just after nine p.m., but that day of action was choreographed well in advance. The British fleet arrived off the bar of Charleston harbor on the first of June, 1776. During the four restless weeks preceding the battle, the American and British forces watched each other closely as they chose their positions and deployed their resources. It was like a slow-motion game of chess, acted out in silence before the first shot was fired.

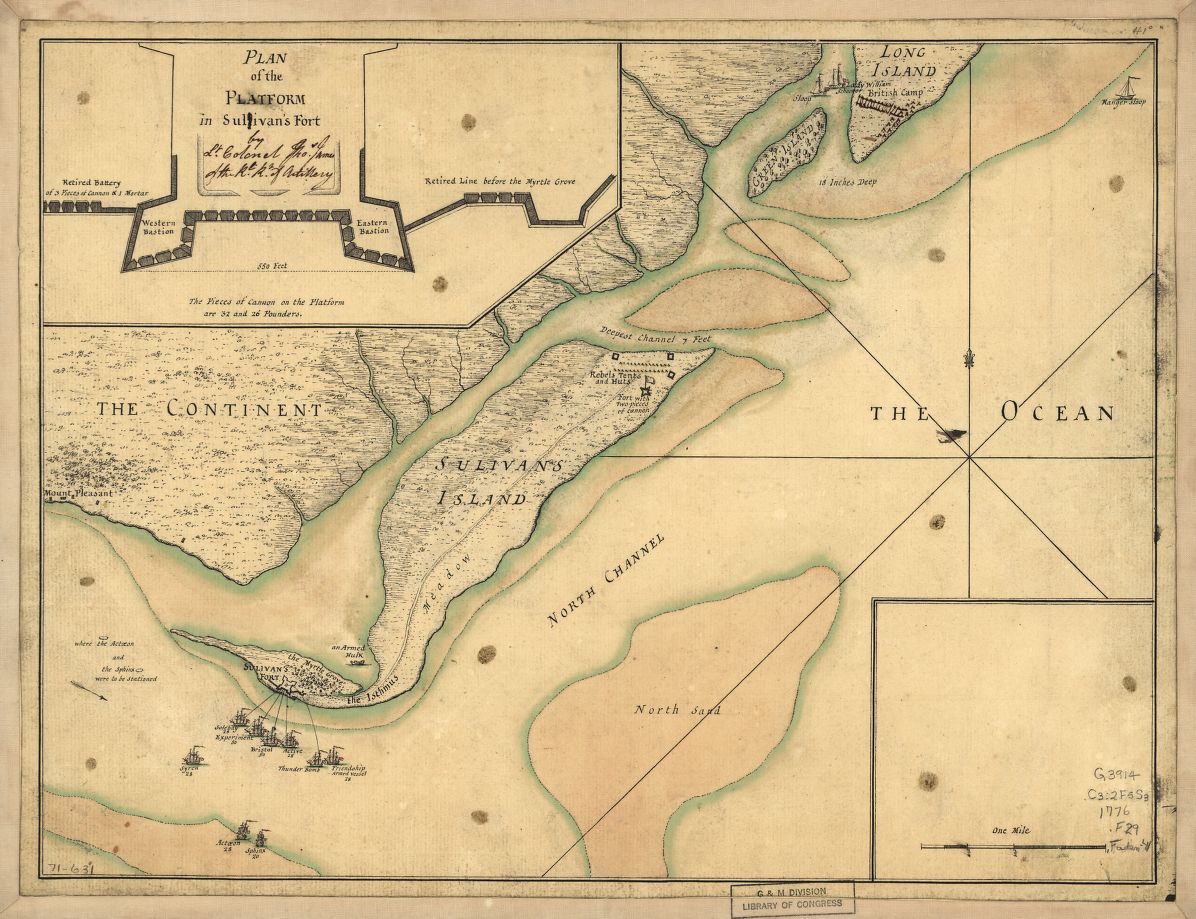

In commemorating the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, I believe it’s important to remember that Sullivan’s Island was not the primary target of the British operations here in the summer of 1776. Certainly, the British navy expected to exchange fire with the American troops in their unfinished fort on Sullivan’s Island, but their goal was to penetrate the harbor defenses and attack Charleston. The British never expected to face such fierce and determined resistance, however, and, frankly, the American command staff did not expect the raw troops stationed on Sullivan’s Island to persevere. How do we know this? Consider for a moment how the American troops were deployed in the weeks leading up to the battle.

The American forces in Charleston numbered just over 6,500 fighting men, including South Carolina Continental troops and South Carolina militiamen, supplemented by Continental troops from Virginia and North Carolina. When the battle commenced on the 28th of June, fifty-six percent (56%) of the American troops were positioned here on the peninsula, to defend urban Charleston. Just over twenty percent (20%) were stationed at Haddrell’s Point, in the old Village of Mount Pleasant. Colonel William Thomson’s riflemen, defending the north end of Sullivan’s Island, constituted about twelve percent (12%) of the total American force. At Fort Johnson, on James Island, Colonel Christopher Gadsden commanded a small garrison that represented about six percent (6%) of the total. Finally, the 435 soldiers inside the unfinished palmetto-log fort on Sullivan’s Island, including the 2nd South Carolina Regiment and a detachment from the 4th regiment, all under the command of Colonel William Moultrie, represented just over six percent (6.5%) of the available American soldiers.[1]

Likewise, the distribution of gunpowder and ammunition was commensurate with the division of the American troops. That is to say, the bulk of the American supply of powder and shot was reserved for the defense of urban Charleston, which was deemed to be the most important asset. The relatively small body of men assigned to defend the unfinished palmetto log fort on Sullivan’s Island were purposefully given a proportionally small supply of ammunition. The American forces here on the peninsula were moderately well supplied with gunpowder and shot before the battle, but Colonel Moultrie knew well before the fight began that he was handicapped by an inadequate share of firepower.[2]

From this sort of analysis, it’s clear that the American army was circling its wagons, to borrow a later expression, around the town of Charleston. Both sides expected the firefight at Sullivan’s Island to be just a prelude to the main event—a naval and amphibious assault on Charleston’s eastern waterfront. To meet this danger, the American commanders positioned the bulk of their artillery behind a palmetto log wall that stretched the length of East Bay Street, and behind the robust fortifications here at White Point.[3] In fact, the prestigious Charleston Artillery Company, commanded by Captain Thomas Grimball, was stationed right here in Broughton’s Battery, which was known as Grimball’s Battery in the summer of 1776.[4]

General Charles Lee, the commander of all the American troops in this area in June of 1776, thought it was folly to devote valuable resources to the defense of Sullivan’s Island. He believed the British navy would quickly decimate Colonel Moultrie’s troops as the warships sailed into the harbor, potentially transforming the unfinished fort on Sullivan’s Island into a “slaughter pen.” Lee would have preferred to keep those troops here on the peninsula, to defend the town, but in the end, he bowed to local pressure. President John Rutledge and the other local military commanders thought it was well worth the effort to attempt to stop the British from entering the harbor, or at least to slow their advance. General Lee reluctantly agreed to their plan, but he ordered Moultrie to spike the cannon and evacuate the fort as soon as his troops had exhausted their limited supply of powder and iron shot.[5]

General Charles Lee, the commander of all the American troops in this area in June of 1776, thought it was folly to devote valuable resources to the defense of Sullivan’s Island. He believed the British navy would quickly decimate Colonel Moultrie’s troops as the warships sailed into the harbor, potentially transforming the unfinished fort on Sullivan’s Island into a “slaughter pen.” Lee would have preferred to keep those troops here on the peninsula, to defend the town, but in the end, he bowed to local pressure. President John Rutledge and the other local military commanders thought it was well worth the effort to attempt to stop the British from entering the harbor, or at least to slow their advance. General Lee reluctantly agreed to their plan, but he ordered Moultrie to spike the cannon and evacuate the fort as soon as his troops had exhausted their limited supply of powder and iron shot.[5]

In this context, we can better appreciate the steely resolution displayed by Colonel Moultrie and his troops on the 28th of June. They knew they were undersupplied and outmatched. They understood that their superior officers didn’t expect them to persevere. They knew that the veteran British troops were expecting to breeze past the unfinished fort with minimal resistance. Despite all these disadvantages, however, those 435 raw American soldiers rolled up their sleeves and dug in for a hard fight.

In the ten-hour battle on the 28th of June, 1776, the British navy aimed nearly 300 cannon at Fort Sullivan and expended approximately 17 tons of gunpowder to fire more than 50 tons of iron shot. The Americans inside the unfinished fort had just 31 cannon and expended just over two-and-a-half tons of gunpowder to fire about 7 tons of iron shot at the British navy.[6] The American forces were outmatched by a ratio of nearly 8 to 1. But yet they won the day, with only twelve men killed, and twenty-five wounded.[7] It was an extraordinary victory. It was heroic, miraculous, providential, even epic. How did they do it?

I can think of at least three factors that sealed the fate of the battle on that historic day. First, the American troops were strengthened by their sincere belief in the righteousness of their cause. Second, the defenders of Fort Sullivan, later renamed Fort Moultrie, were empowered by the resolute determination displayed by their commander, William Moultrie. Third, the Americans were aided by the resilient properties of Mother Nature: the spongy palmetto tree trunks, the shock-absorbing sand within the fort’s walls, and the deceptive water courses that confused British intelligence and prevented the enemy from positioning troops to their advantage.

And finally, the men who faced the British war machine on the 28th of June were inspired to fight on by the brave acts of their fellow soldiers in the heat of the battle. Early in the day, when the flag of the Second Regiment was shot down by a British cannonball, Sergeant William Jasper braved a hail of cannon fire to rescue the fallen flag and replant it on the rampart. His reckless enthusiasm was more than folly. The flag was a powerful symbol that represented their cause. Spirits drooped when the flag fell, but Sergeant Jasper revived the spirit of determination at a critical juncture in the battle.[8]

Likewise, Moultrie’s men were inspired by the dying words of Sergeant McDaniel, who was disemboweled by a British cannonball. “Fight on, my brave boys,” McDaniel said to his comrades with his last breath. “Don’t let liberty expire with me today.” Each year on the 28th of June we honor the memory of Sergeant McDaniel and his brave compatriots by recalling their deeds and the eternal debt we owe to their sacrifice.[9]

Had the British plan prevailed on that 28th of June, 1776, the engagement at Sullivan’s Island would have been merely the appetizer course of a feast of violence in which downtown Charleston was the main course. The history of South Carolina, and of the United States in general, would have taken a far different course had the British prevailed on that fateful day. But the brave boys in blue on Sullivan’s Island won the day and spoiled the British appetite for both the surf and turf of South Carolina.

In the course of American history, our nation has survived hundreds of battles, but not every battle is remembered by an annual commemoration. We have general days of remembrance, like Memorial Day and Veterans Day, but many battles—in fact, most battles—are not individually commemorated on every anniversary. Why is the Battle of Sullivan’s Island different? Why have people been commemorating the anniversary of this battle every year since 1777? Why was a society formed specifically to perpetuate the memory of this battle? The answer, in short, is that the outcome of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island was so unexpected (both to the victors and the losers), so inspiring (to those who witnessed the event and those who came after), and so important (to the people of South Carolina and to the larger American struggle for independence).

As a teacher, I’m always thinking about how to summarize big stories into smaller, bite-sized themes that are easier to digest. So what lessons can we learn from the Battle of Sullivan’s Island? What message summarizes the spirit that won the day? What theme can we derive from this victory and pass along to future generations of Americans?

As a teacher, I’m always thinking about how to summarize big stories into smaller, bite-sized themes that are easier to digest. So what lessons can we learn from the Battle of Sullivan’s Island? What message summarizes the spirit that won the day? What theme can we derive from this victory and pass along to future generations of Americans?

Personally, I draw inspiration from a phrase coined by John Rutledge, president of South Carolina on the 28th of June, 1776. During the height of the battle, when observers standing right here at White Point witnessed the success of the American firepower, President Rutledge ordered a boat to deliver an extra 500 pounds of gunpowder to Sullivan’s Island. Along with the powder, Rutledge also scribbled a note to Colonel Moultrie, urging him to use his supply of ammunition slowly and deliberately. In the heat of battle, Rutledge concluded his note by advising Moultrie, “Cool, and do mischief.”[10]

That pithy phrase, rendered in more verbose language, might sound like this: Steady your nerves, sight your targets as precisely as possible, and use the resources at hand to inflict as much damage as possible to the enemy. In a civilian context, we might translate Rutledge’s advice like this: Calm your mind, identify your goals as clearly as possible, ignore the distractions of life, and work diligently to overcome the obstacles that stand between you and success. I think that’s a noble admonition, both in 1776 and in the present day. “Cool, and do mischief.”

I’d like to conclude my remarks today by recalling another anecdote from the summer of 1776. On the morning after the battle, General Charles Lee sent a short note to William Moultrie promising to visit the battle-scarred fort soon. In the meantime, the general wrote, “I have applied for some rum for your men. They deserve every comfort that can be afforded them.”[11] And so, on this hot summer’s day, I think it’s fitting that we should all raise a glass to the memory of those brave men whose triumph we celebrate today. Whether your glass contains a celebratory dram of rum or just plain refreshing water, I invite you to join me in toasting the memory of those brave men who fought and died for our liberty. Cool, and do mischief!

–Nic Butler

–ccpl.org

[1] The notes of William Henry Drayton (d. 1779) provided his son, John Drayton, with excellent materials to reconstruct the numbers of American soldiers in the Charleston area in the summer of 1776. See John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 2 (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1821), 282, 291–6.

[2] Drayton, Memoirs, 2: 296–97.

[3] For eye-witness accounts of these palmetto works, see Paul G. Sifton, ed., “La Caroline Méridionale: Some French Sources of South Carolina Revolutionary History, with Two Unpublished Letters of Baron de Kalb,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 66 (1965): 108; Banastre Tarleton, A History of the campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (London: T. Cadell, 1787; Reprint, Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Company, 1967), 13; Bernhard A. Uhlendorf, ed. and trans., The Siege of Charleston. With an Account of the Province of South Carolina: Diaries and Letters of Hessian Officers from the von Jungkenn Papers in the William L. Clements Library (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938), 95. The palmetto wall is visible in the inset of a map titled The Harbour of Charles Town in South Carolina from the Surveys of Sr. Jas. Wallace Captn. in his Majesty’s Navy & others with a view of the Town from the South Shore of the Ashley River (London: J. F. W. Des Barres, 1777). Note that the illustration of the fortified town in the inset of Des Barres’s map appears to omit the wharves on the east side of East Bay Street. An undated, ca. 1779 map of Charleston’s fortifications, found among the papers of Sir Henry Clinton at the Clements Library at the University of Michigan (Small Clinton Map No. 314), shows the line of “a breastwork of palmettos” on the east side of East Bay Street, but to the west of the wharves.

[4] For references to “Grimball’s Battery” in 1776, see “Diary of Captain Barnard Elliott,” in Charleston Year Book, 1889, 212; and Drayton, Memoirs, 2: 321.

[5] William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, volume 1 (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 141–42, 166.

[6] Drayton, Memoirs, 2: 196–97.

[7] Drayton, Memoirs, 2: 302; Moultrie, Memoirs, 1: 177.

[8] Moultrie, Memoirs, 1: 179. Drayton, Memoirs, 2: 298.

[9] Moultrie, Memoirs, 1: 177. Drayton, Memoirs, 2: 303.

[10] Moultrie, Memoirs, 1:167.

[11] Moultrie, Memoirs, 1:168.