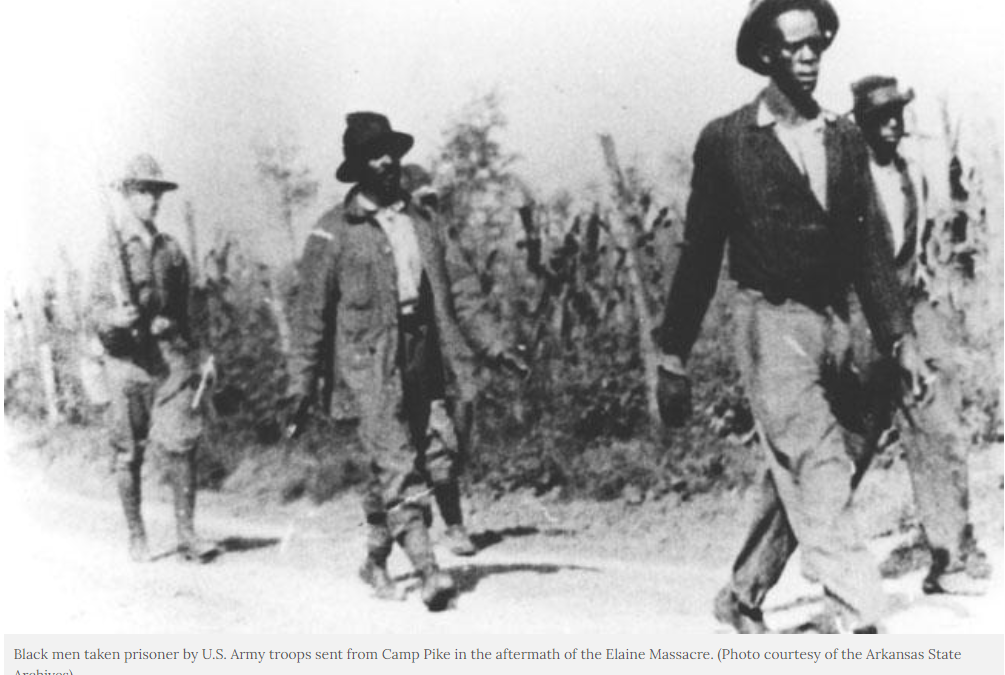

This week marks the 102nd anniversary of the Elaine Massacre, when a union organizing attempt by Black sharecroppers in rural Elaine, Arkansas, was met with extreme violence by white people. The killing spree, which began on Sept. 30 and lasted for two days , left hundreds of Black people dead. Five white people died. Hundreds of Black residents of Phillips County were arrested on spurious charges, and a dozen sentenced to death; they were known as the Elaine Twelve, and their death sentences would later be thrown out by the Arkansas Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court. Fifteen years later, when a group of Black and white sharecroppers and tenant farmers met about 100 miles north of Elaine in Tyronza, Arkansas, to organize the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, the massacre and its consequences were on their minds.

In 1974, Southern Exposure, the print forerunner to Facing South, published a collection of oral histories titled “No More Moanin’: Voices of Southern Struggle.” For that issue, Sue Thrasher and Leah Wise interviewed several people who had been involved in the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and they constructed a lengthy oral history of the union from those interviews. We’re publishing those oral histories on the Facing South website for the first time this week.

We’re also publishing from that same issue of Southern Exposure this account of the Elaine Massacre. Written by Wise, it was drawn from the oral histories collected by her and Thrasher, as well as from several other contemporary sources. Since then, historians have discovered much more about what led to and resulted from the massacre. An online exhibit from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock details many of the new discoveries and the current scholarship on the massacre.

Facing South has reported on the centennial of the Elaine Massacre and the community’s continued push for restorative justice and reparations; you can read those stories here and here.

Editor’s note: The oral histories as originally published include a racial slur spelled out in full. We are publishing it here as it occurred in the original.

The Elaine Massacre

By Leah Wise

The following description of the Elaine story is a composite of information gathered from an account in Crisis, December 1919, by far the best account written; from a report entitled, “Lynching and Debt Slavery,” written by NAACP Field Secretary William Pickens and published by the American Civil Liberties Union; and from my own travels through eastern Arkansas, from Marianna to Elaine, talking to individuals who would briefly recount their memories and then send me down the road a piece to a more knowledgeable source. I talked with almost a dozen folk that way, and ended up in Elaine interviewing its oldest citizen, who everyone said (and so he claimed) knew the story better than any man living. But senility prevented the story from getting out.

Elaine, Arkansas, one of those small towns built upside the railroad, is located in Phillips County, which is bordered by the Mississippi River to the east. In 1910, 78.6% of the population of Phillips County was black. There were 3,598 black tenants and sharecroppers who farmed 81,000 acres, and only 587 black farm owners in that year. An area of rich alluvial soil, two-thirds of the agricultural production of the county was in cotton, which became a booming business during the war years when cotton prices quadrupled, up from 11 cents a pound in 1915 to 40 cents a pound in 1919.

The black croppers were getting only 15 cents a pound for their cotton from the planters, less than half the going price. Many of them received no settlement from the planters for their cotton taken in the fall of 1918 until July, 1919, and never received a monthly statement of account which would have enabled them to verify charges to their accounts. These conditions prompted 68 blacks from the Fairthy plantation to hire a lawyer to sue their landlords for statements of their accounts and a just settlement. Some had planned further to go before the federal grand jury to charge certain planters (owners, managers and agents) with peonage. They hired a white attorney from Little Rock named Bratton, the same Bratton who a few years earlier had prosecuted black peonage cases in Phillips County for the government and had convicted a half dozen planters. (The Phillips County suit had followed a government inquiry into alleged peonage of Italian laborers in the South.) Bratton’s fee was $50 per tenant, plus a percentage of the money to be collected from the landlords. The black tenants held secret meetings to collect the money for Bratton’s advance and the treasury as well as to gather evidence and facts to solidify their legal case.

According to the Crisis account, at the same time another organization, a union of black cotton pickers, arose whose purpose was to organize a strike for higher wages. They did strike, refusing to pick cotton until they got better pay. A substantial number of the cotton pickers were the wives and daughters of sawmill hands, whose relatively fair pay enabled them to bargain over wages. (There is simply not enough information to determine whether these organizational efforts were absolutely independent, though it seems unlikely.)

Because of the tense racial climate in the country at the time — there had been recent race riots in East St. Louis, one in Chicago and another in Washington, D.C., and an increase in KKK activity — black folks in the area had begun amassing weapons and ammunition for defense. It is unclear whether the sharecropper groups initiated and organized this activity or whether it merely became one of their main programs. It is probable, however, that organization was involved, organization that included black professionals in Helena, who several interviewees said obtained the weapons. They also recalled that a conflict was anticipated. One reported that black folks had a whole boxcar of ammunition. Another said they had machine guns and high powered rifles. The interesting, and unresolved, aspect of their organization is the possible role of Garveyites. One informant who proudly defined himself as a “race man,” recalled that a Garvey local had tried to get off the ground in the Helena area without much success. Another said he suspected that Dr. A. E. Johnston, a prominent dentist and property owner of Helena and one of the four Johnston brothers lynched during the riot, was a Garveyite. Carrie Dilworth, from central Arkansas, said that in her youth she had chanted the slang expression, “Don’t be no fool with Marcus Garvey,” which she said meant that he would get you killed and which she understood to refer to the Elaine massacre. Stith knew the same expression. The old man in Elaine claimed that a man from Winchester, Arkansas, was responsible for organizing the sharecroppers and promised them they would win 40 cents a pound for their cotton. Others I interviewed knew of no Garvey activity in the area.

The white people in the area learned of these organizing efforts and of the gun buying which came from white Helena merchants and express offices, and began meeting to figure out how to “break up the whole business and put the Negroes in their place.”

The first incident that preceded the main confrontation in Elaine, mentioned only in the Crisis account, involved a drunken white man from Helena named John Clem, who terrorized the black community of Elaine one Sunday by shooting up their area. Suspicious that he was sent to spark a riot, black folk kept off the streets and notified the sheriff at Helena, who did nothing; John Clem continued his gunplay the following day. The second incident occurred on Tuesday at a church near Hoop Spur just north of Elaine, where the croppers were meeting. The Crisis article reports several versions of the event. The first version says that the deputy sheriff, a “special agent” and a black trustee drove up to the church in a car and tried to enter the church “to investigate” the meeting and were refused admittance. Trying to force their way in, they fired into the building whereupon the blacks within fired back, killing the special agent and wounding the deputy. The second version comes from the words of the trustee (whose presence is mentioned in no other account) who said that the deputy and the special agent were ambushed by two other whites and a black. The initial statements of the wounded deputy corroborated that story. This version, however, was carefully made “inoperative” a few days thereafter. The third version, the official white version, became: blacks in the church were armed and fired on the two whites without provocation when their car had happened to break down in front of the church.

The memories of those interviewed were that the blacks had guns in the church for protection and that they had been forbidden to meet.

In essence, a “nigger hunt” ensued. Whites sent their families to Helena for safety while car and truck loads of white men — headhunters — poured in from neighboring counties in Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas. Woods were scoured. Homes were fired into. Hunting parties often travelled faster than the news, catching many blacks ignorant and defenseless. The four Johnston brothers of Helena were intercepted upon return from a squirrel hunt and were lynched. The next day, in Ratio, 12 miles south of Hoop Spur, the son of Attorney Bratton was meeting with representatives of the Fairthy 68, who were anxious to go to court, to collect the fees. They were encountered by one of the white roving bands, arrested, sent to jail in Helena, and charged with murder. Bratton was nearly lynched; Governor Brough swore in special guards to protect him and surround the jailhouse, where he was held for 31 days without bond and eventually was released without trial. Those interviewed spoke of a pitched battle. Governor Brough sent in state troopers as well as 500 federal troops from Camp Pike. One businessman told me he understood that the only way they got the blacks to surrender was by sending in black troops; the croppers wouldn’t shoot their brothers.

Over one thousand black men and women were arrested by the soldiers and confined in unsanitary “stockades” and denied any contact with attorneys or friends. Another 200-300 were arrested and jailed in Helena. Each was personally investigated by army officers and the select “committee of seven,” comprised of two planters, a cotton factor, a merchant, a banker, the county sheriff and the mayor of Helena, which functioned with Governor Brough’s sanction. “Innocent” blacks were let go only after a white appeared to vouch personally for them, which was done only after a given wage was agreed to. That settled the strike. Black farm owners who had no whites to vouch for them stayed incarcerated longest and frequently lost their land as a result.

Within a month 66 had been tried and convicted. Trials averaged 5-10 minutes and it was reported that electric connections were used on the witness chair to scare the defendants.

The Little Rock trial of the twelve men facing the electric chair received the most attention. One of the people interviewed had an uncle who attended the trial who reported that the judge asked Dr. E. C. Morris, the prominent Helena minister and president of the National Baptist Convention, whether he thought the men were guilty of murder in the first degree. After asking for an explanation of the charge from the black and white attorneys, he answered no. Another explained to me that because four of the twelve were Masons, they didn’t get electrocuted, for at the time all leaders had to be Masons, from a railroad engineer to county sheriff on up to the president of the U.S. It was clear that the attack on debt slavery had been squashed.

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.