Two years ago, Charleston historian English Purcell was surfing Google Earth, taking note of the scores of outbuildings that still survive behind the city’s larger historic homes.

Purcell, an administrator for the popular Facebook site, Charleston History Before 1945, posted a comment about how neat it would be to tour some of them.

The post caught the eye of Joe McGill, head of the Slave Dwelling Project, a nonprofit dedicated to raising awareness about surviving slave quarters. His message back to Purcell was brief: “Let’s make it happen!”

The two approached Historic Charleston Foundation, and their inaugural “Beyond the Big House” tour sold out last year. The second one is scheduled Sept. 15, and will feature a self-guided tour of a different set of dependencies and other sites.

Like the first tour, the day will feature an assortment of kitchen houses, carriage houses and former slave quarters, some rarely on public display.

Purcell said there are many more outbuildings than most people realize.

“The main takeaway is that the city of Charleston did not function without the enslaved on the peninsula. They did not just live on the plantations, and that is what we’re trying to get out there,” she said. “As Joe would say, ‘Tell the whole story.’ ”

‘People just don’t know’

Not all the buildings on this year’s tour are obvious.

While it does include some traditional dependencies, such as a surviving kitchen house behind a Society Street home and a carriage house on Hasell Street, it also features the story of single house at 35 Chapel St.

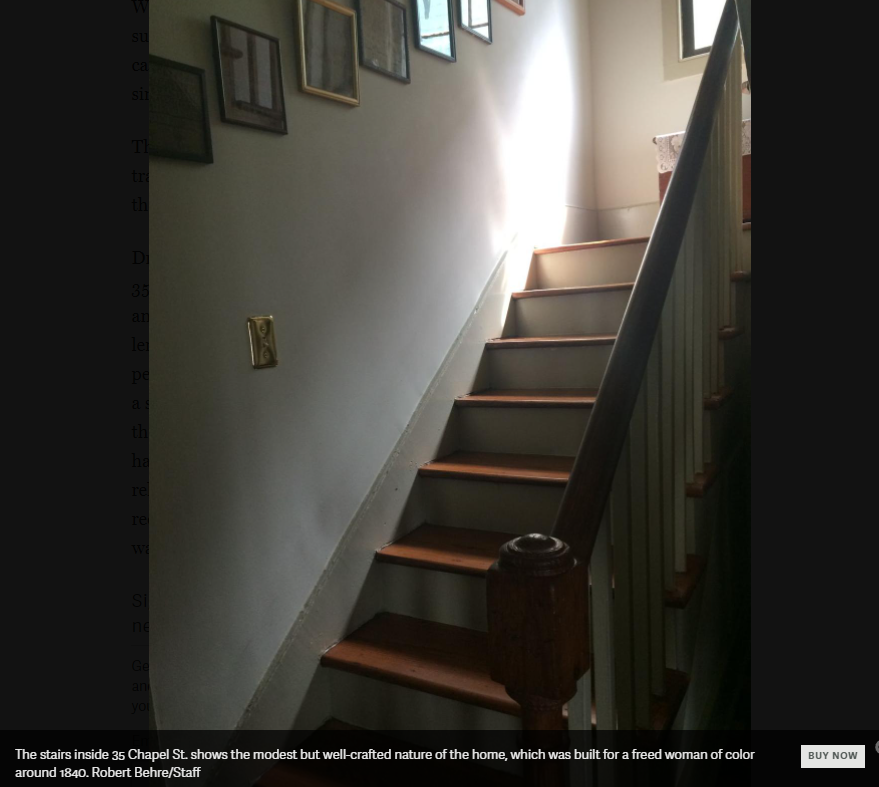

This house, with a single-story piazza, doesn’t look like a traditional outbuilding, but records show it was built behind the Charlotte Street home of R.B. Holmes around 1840.

Dr. Lou Weinstein, current owner of 35 Chapel, has dived into its history and learned that Holmes essentially lended land to Sylvia Miles, a free person of color who was married to a slave, William Miles, and had three children. Holmes and Sylvia had some sort of special relationship, but Weinstein said the record isn’t clear as to what that was.

What is clear is that her house was a crowded one. The 1850 Census lists 35 Chapel as home to six free people of color, including Sylvia Miles’ three children, and a dozen slaves. Her husband, William Miles, lived in a separate home not far away.

Weinstein describes Sylvia Miles as a true entrepreneur, taking in laundry as well as boarders. He tracked down her tombstone and death record, which notes she died of “physical exhaustion.”

“I’m proud of this woman,” he says. “I’d love to find descendants of this woman. I’d love for them to come and have dinner with us.”

“This tour allows us to tell these stories people just don’t know,” says Fanio King of the Historic Charleston Foundation. “We’re always researching in order to be able to tell these stories more fully.”

Discovering what’s hidden

King says this year’s tour focuses on dependencies on either side of Calhoun Street, which was known as Boundary Street during antebellum times and differentiated the city from its northern suburbs.

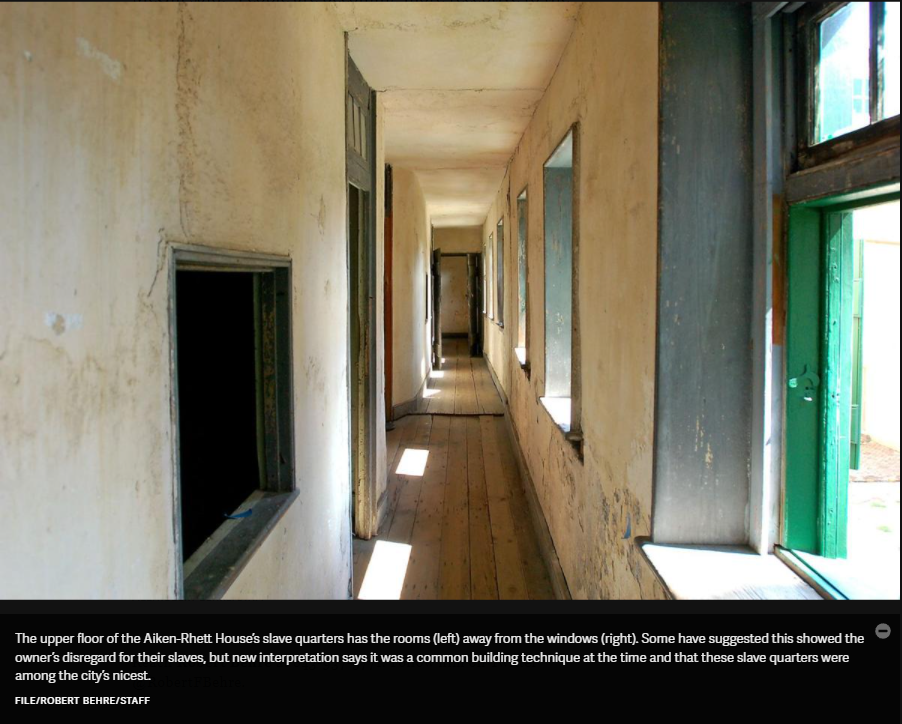

The tour also includes the foundation’s Aiken Rhett House museum, which has one of the largest and best preserved set of outbuildings in the city. The two main ones include a carriage house and kitchen building with slave quarters on top. A recent archaeological dig there unearthed a massive trove of artifacts now displayed inside. Even its privies survive.

Most other outbuildings have been renovated into additional living space, and many have been connected to the main house with hyphen additions.

“The important thing is that these buildings remain on the landscape,” King says, “so we can continue to talk about their history and who lived and worked in them.”

The “Beyond the Big House” tour is yet another example of the city interpreting its African-American history, a part of its past that previously received short shrift.

“These buildings are physically hidden in terms of accessibility but they’re also hidden in that we, as tourists, as consumers of American history, that’s not usually what has been fed to us,” McGill said. “People are becoming more receptive to the mission of what the Slave Dwelling Project is trying to accomplish.”

“It’s critical to telling the complete story of Charleston,” Purcell added.

–postandcourier.com