North Carolinians have long called themselves Tar Heels, and “Tar Heel” is a badge of pride—and, indeed, preeminence—in a variety of fields from scholarship to basketball. “Tar Heel” is but one of many nicknames for the residents of specific states. Tar Heels’ southern neighbors are “Sandlappers,” residents of Indiana are “Hoosiers,” and Oklahomans are “Sooners.” Some of these nicknames have simple explanations, while the origins of others are more obscure; very little is known about just why North Carolinians are called “Tar Heels.” Common sense links it to the naval stores industry that dominated the eastern part of the state in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but there has been surprisingly little scholarship on the question. An analysis of printed material from the nineteenth century, however, reveals a complicated story that hinges on region and class, race and identity. What follows is a tentative but hopefully plausible account of how “Tar Heel” emerged in the decades before the Civil War, how eastern North Carolina’s experience in the war led to other southerners applying the disparaging term “Tar Heel” to North Carolina soldiers, and how during the course of the war North Carolinians came to embrace the term with pride.1

We begin with the second half of the name: “heels.” An 1859 newspaper article noted that North Carolina citizens (which, in that era, meant only whites) were generally known as “Rosin heels,” but the term “rosin heel” was much older and more widespread. Figuring out where and why some southerners were called “rosin heels” provides a foundation for figuring out “Tar Heel” and shows the relationship between class and economic activity and regional identity. The earliest use I have found of the term “rosin heel” comes not from North Carolina but from West Florida around 1820. In his 1826 book Recollections of the Last Ten Years, Timothy Flint described a landscape untamed by agriculture where men could extract valuable products. Live oaks in the swamps would provide masts and spars for ships, pine trees could produce pitch and tar, and the high grass growing among the pines was perfect grazing for cattle. In this Edenic place where people could live without farming, “The people, too, are poor and indolent, devoted to raising cattle, hunting, and drinking whiskey. They are a wild race, with but little order or morals among them; they are generally denominated ‘Bogues,’ and call themselves ‘rosin heels.’” A few years later, someone described a spectator at a horse race near Natchez as “a raw-boned rosin-heel.” In the 1850s, a New Orleans journal explicitly placed the “rosin heels” in the Piney Woods: “the ‘Rosin Heels,’ as our Piney Woods fellow citizens are quaintly called.”2

During the course of the Civil War North Carolinians came to embrace the term with pride.

“Rosin heel” was a derogatory occupational term analogous to “hayseed” for farmers or “linthead” for cotton mill workers, terms aimed at those whose work made them dirty with the substance they produce or process. Typically coined by those whose work keeps them clean (or at least cleaner than others lower down the class ladder), the epithets also dehumanize those designated by collapsing the difference between the workers and the materials they work with. To collect the rosin that made turpentine from pine trees, workers chipped off some of the outer bark of longleaf pine trees with axes and placed wooden boxes at the bottom, a little ways off the ground, to collect the rosin as it flowed out of the wounded tree. Then, workers dipped the rosin from each box with a sort of paddle and transferred it to a large barrel. “Although dipping was a light task requiring little physical strength,” explains historian Robert B. Outland III, “it was a dirty operation that smeared the workers’ hands and clothing with gum [rosin].” Poor workers in the hot climates of the Piney Woods probably went barefoot during the warm months when rosin was being collected, and thus very likely collected a fair amount of it on their heels.

The term “rosin heel” seems to have been applied equally to those who worked in the Piney Woods’ naval stores industry and those who simply lived in the area. An 1834 article described

the dark green woods of Florida, in the hands of a set of merry and unique fellows, bearing the appropriate name of “Rosin Heels.” It is a spectacle worth seeing, to observe them, in those primeval, dark-green woods, of a night, conversing freely with the “soul of corn,” and making the solemn forests echo with their peals of laughter, while relating stories, little dreamed of in the philosophy of books.

These rosin heels are workers, but they are not working terribly hard. Like the poor residents of poor lands everywhere, the improvidence of the land is transferred as a personality trait to those who inhabit it. Feckless and drunken, the “rosin heel” was one of many varieties of poor southerners, second cousin to a “sandhiller,” and kin to a “clay-eater.”3

It is likely that “rosin heel” became more common after its use in a widely reprinted 1840 newspaper article. North Carolinian Joseph Seawell “Shocco” Jones had gone to Mississippi the year before to perpetrate a hoax about banking on the gullible people of that state, whom he described as “rosin heels.” “Rosin heel” also entered political discourse as a persona that writers could use in order to criticize politics from a “common-sense,” “down-home,” and usually racist perspective. For instance, in 1851, a correspondent signing himself “Jake Snivencroft, C.D.” (“C.D.” stood for “Constetushional Demekrat”) wrote a letter from “Piny Woods—Up on Rosin Heel Kreek” complaining about the formation of the new “Unionister” party, a short-lived political party designed to bring together southerners who supported the Compromise of 1850 and opposed secession.4

When the South’s speculative boom in cotton collapsed in 1837, it disrupted the entire region’s economy and some southern planters turned to other options. In eastern North Carolina, this meant that a number of planters got into turpentine production on a large scale. This new activity, along with increased outlets for the products of the Piney Woods, led to a boom in the 1840s. Cotton eventually recovered, and in the 1850s, it went through a boom of its own, with prices rising enough to pull many peripheral regions of the South into the cotton economy. Cotton planters cut down the pines in southwest Georgia—or, rather, their slaves did—so they could plant the land to cotton and get rich. Eastern North Carolina was not immune to this new cotton boom, but cotton did not displace the turpentine industry there as it did elsewhere. By the end of the 1850s, then, being a “rosin heel” was not exclusively associated with North Carolina, but it had become a much more geographically focused designation than it had been twenty or thirty years earlier.5

That accounts for “heels” and how sticky pine products came to be associated with them, but we remain far from “tar.” The association of tar with heels has an entirely different genealogy than “rosin heel,” and the best way to understand why is to consider the differences between rosin and tar.

Within the naval stores business, “rosin” has two different meanings. It might refer to “the residue that remained in the still after the raw turpentine finished distilling,” or it could refer to the sap gathered directly from the pine trees, though this substance was commonly called “gum.” In either case, rosin was a light, amber-colored material. Tar, on the other hand, was typically produced “by firing pine branches and logs in slow-burning kilns” and was proverbially black. Since tar was widely used—for protecting rigging on ships, for lubricating the axles of wagons, and for marking sheep and treating wounds in livestock, among other things—it was a substance many people came in contact with regularly, and its stickiness meant it was easily transferred to people. In fact, sailors climbing tarred rigging came to be called “tars,” and variations of the phrase “a dash of the tar brush” was used as early as 1796 to refer to someone of mixed race.6

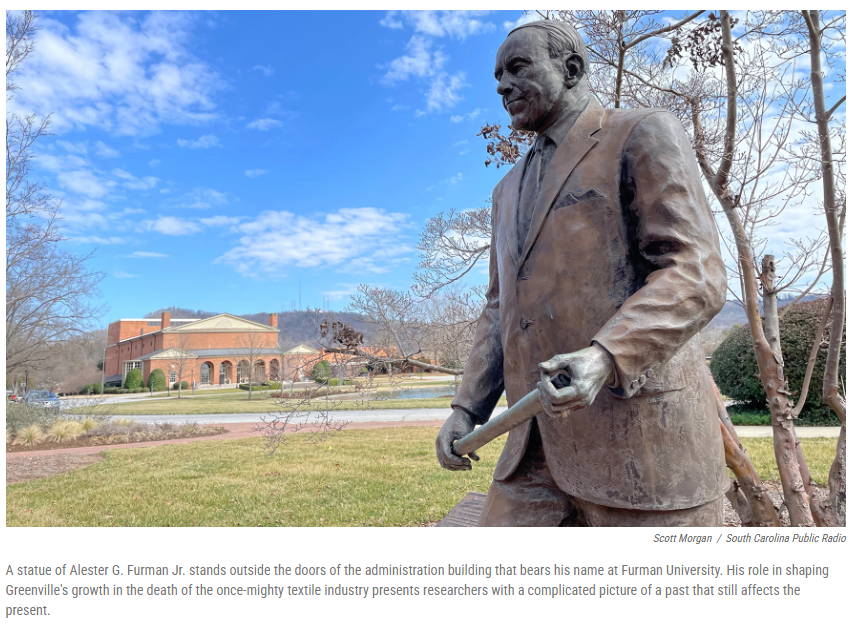

“Rosin heel” was a derogatory occupational term analogous to “hayseed” for farmers or “linthead” for cotton mill workers. “The Turpentine Industry in North Carolina,” by W. P. Snyder, Harper’s Weekly, May 17, 1884, p. 312.

Within the United States, ‘tar’ developed more specifically racial connotations.

Within the United States, “tar” developed more specifically racial connotations, perhaps in part because the 1840s surge in turpentine production coincided with the return of the issue of slavery to prominence in national politics, due to the rise of the antislavery movement and the Mexican–American War. From the early 1840s (if not earlier) white Americans, in the North and the South, began to use the expression “tar on a nigger’s heel” or some close variation, often in connection to politics. A sarcastic announcement of an 1843 antislavery convention in London said, “Gumbo Chaff is to be chief cook and bottle washer with tar on his heel to pick up the pennies.” In October 1848, a newspaper article in Joliet, Illinois, criticized Martin Van Buren’s position on race, using a hayseed sort of dialect. At the time, Van Buren was running for president as the candidate of the Free Soil Party after breaking from the Democrats. Contrasting his current antislavery position to his earlier loyalty to the South and the Democratic Party, the author wrote, “He stuck to the South then like tar to a nigger’s heel.” The phrase focuses on race; it is derogatory in tone; and it is applied to someone who has betrayed their earlier position on racial issues. This usage is significant because we will see elements of it resurface when “tar heel” comes to be applied to North Carolinians. Around the mid 1850s, the phrase “tar on the heel” (or, more often, rendered in black dialect as “tar on de heel”) seems to have entered the linguistic landscape. A couple years later, a passenger on a steamship on Lake Erie complained, “The heat on board was most intense—so great that the pitch on the decks became liquid, and we went tracking it around as if we had ‘tar on de heel’ in good earnest.” In 1855, the Edgefield Advertiser got into an editorial quarrel with another South Carolina newspaper, the Yorkville Enquirer, and eventually sought to settle the spat by printing, “We now make the ‘amende honorable’ by stating that ‘there is no tar on that nigger’s heel.’”7

As “tar on de heel” gained currency, it appeared in 1855 in Kansas, a place where race and slavery was a central issue. A pro-slavery newspaper commented on a controversy over a bill introduced in the Kansas territorial legislature to make inciting a slave rebellion a capital crime. “The ‘tar on the heel’ papers have published the bill in all its details, cried over it, boo-hooed over it, and made such a blubbering about the inquisitor moonshine,” the newspaper wrote, “that their readers probably suppose that such is really the law of Kansas.”8

The most surprising thing about the origins of the phrase “Tar Heel” is that it appears the first person referred to as a Tar Heel was none other than Frederick Douglass.

The most surprising thing about the origins of the phrase “Tar Heel” is that it appears the first person referred to as a Tar Heel was none other than Frederick Douglass. An item from the Germantown (Ohio) Emporium commented on the results of the 1852 presidential election, foreseeing the realignment of political parties that was indeed gaining momentum at that moment and decreasing the distance between Democrats and Whigs on the most important issue of the day: slavery. The editor wrote,

Democrats will now discover that there are some decent people among the Whigs, and vice versa. A Whig lady can now lend her Democratic neighbor her coffee-mill, and in turn, borrow an egg to put in her pan-cakes. Andrew Jackson Croutcutter will now be allowed to play with Henry Clay Snakefeeder’s pet hog; and Fred Douglass Tarheel will se-saw with John Quitman Screwdriver, and take the South side of the fence. All will go just as if one person were as good as another!

To the extent it is possible to untangle the humor here, it appears that the editor is taking familiar names and adding a funny element to them that reflects their politics. Henry Clay is given “Snakefeeder” because he had supported the re-chartering of the Second Bank of the United States, which Andrew Jackson and the bank’s other opponents considered a “hydra of corruption.” The reasoning for the nicknames of Andrew Jackson and John Quitman are a bit more puzzling, but in case anyone had forgotten the most salient fact about Douglass—his race—he is called “Tarheel.”9

A related form of this “tar on de heel” phrase became a staple of minstrel stage humor. It is probably easiest to simply print the story as it ran in many newspapers in early 1861, though it first seems to have appeared in August 1860 in the Cleveland Plaindealer.

The Cleveland Plaindealer, on the authority of a Southern friend, tells how the saying “Dar’s a niggar got tar on his heel,” is used among the slaves on the plantations. He recently visited a plantation near Memphis, Tenn., and at night, when the darkeys’ work was done, they assembled to pitch coppers. The cents gradually disappeared in a very mysterious manner. The most rigorous search revealed no clue to them. The stock of coppers had dwindled fearfully, when light seemed to break upon one of the darkeys, and he yelled, “Dar’s a nigger got tar on his heel!” Great confusion followed the announcement, and the darkeys commenced seating each other violently on the ground. At one time twenty darkeys were seated on the ground, while twenty more had their legs in the air a-looking at their heels. The miscreant was at length found. The black wretch who sought to bring a time-honored and healthful game into disrepute, was finally discovered. An old negro, who was too lame to indulge in the games, and who had before been (like Gen. Julius Caesar’s wife), “above suspicion,” had covered his heels with tar. Under pretence of seeing fair play, this elderly colored person had made himself very conspicuous among the pitchers, volunteering his services as judge on all disputed points, and all the while the sly old coon was treading on the coppers. They stuck, of course, and when his tarry heels were turned up, they revealed “a right smart chance” of cents.

The story had no doubt been in circulation for some years before 1860, as the 1842 example above suggests. An 1857 editorial in a Nashville newspaper about the Whigs and the Know-Northings said, “Surely they will not consent to be carried as trophies over to the ranks of whiggery! They will not willingly agree to represent silver dollars sticking to the tarred heels of political gamblers, whose single idea is—spoils!” Here we see the conjunction of “tar” and “heel” in a specifically racialized construction, and one that implies deceit and treachery.10

Perhaps the key document in tracing the transformation of “rosin heel” as a general term for poor white residents of the Piney Woods to “Tar Heel” as a specific reference to North Carolinians is a letter published in a Tarboro, North Carolina newspaper in 1859 by someone calling himself “Old Tarbry.” In late 1858, a group of residents of Tarborough petitioned the Post Office to change the official name of the town, or at least its post office, to “Tawborough” because they “became prejudiced against the use of tar, whether as a word or a commodity.” “Old Tarbry” points out that “The slang name of North Carolina is the ‘Tar, Pitch and Turpentine State’” and that “Her citizens have been dubbed ‘Rosin heels.’” The phrase “Tar, Pitch and Turpentine State” had indeed been used to describe North Carolina, being fairly widely disseminated in an 1842 article in the New Orleans Picayune, for instance, as the turpentine boom was starting. “Rosin heel,” as we have seen, was used for both North Carolinians and other white Piney Woods residents. What is intriguing about this document is how close it comes to applying “Tar Heel” to North Carolinians. We have the reference to “rosin heels” and the notion that “tar” is distasteful for some reason, a combination that would come together when the Civil War came to North Carolina in late 1861.11

We have the reference to “rosin heels” and the notion that “tar” is distasteful for some reason, a combination that would come together when the Civil War came to North Carolina in late 1861.

Up until the shelling of Fort Sumter, many North Carolinians remained Unionists, and many remained so throughout the war. Along with significant areas of dissent in the mountains and in some parts of the central region of the state, eastern North Carolina was an area with “flexible loyalties,” as Judkin Browning points out. Some of the first North Carolinians during the war who could have been described as “Tar Heels” (but, as far as I know, were not) are probably Unionists in the eastern portion of the state who were tarred and feathered by their Confederate neighbors. The loyalty of this region was tested even further at the end of August 1861, when Union forces seized the forts guarding Hatteras Inlet, securing Union control of Pamlico Sound and the mouths of the Neuse and Tar rivers, and taking seven hundred prisoners in the process. The pride of North Carolina was damaged by the Union capture of Confederate territory, and the captured prisoners were criticized for not successfully defending the inlet.12

Tar seeps into the story in an account of the transportation of the North Carolina prisoners to Fort Lafayette on Staten Island. A reporter described their pitiful condition: “The men are dressed in gray, with felt hats of all varieties, giving them a rough appearance.—There has also been an evident lack of soap and razors, and a large majority are bare footed, or nearly so.” “There are,” the reporter went on, “among them men of all ages and condition, from the tar boiler to the merchant and aristocratic slaveholder, and from boys of fifteen to men with gray hairs.” However, these assorted eastern North Carolinians do not appear to have been terribly enthusiastic Confederates. The same article suggests, “The conduct of the prisoners with few exceptions, was such as led to the belief that they were not displeased with their capture. Their condition and fare at the Hatteras forts were anything but comfortable, and many of them assert that they were forced to take up arms and to fight against their will.” Here, we see the beginning of an association of disloyalty to the slaveholders’ Confederacy among North Carolina soldiers with tar and those who made tar around the Tar River, a connection that would be drawn even more strongly the following year.13

In February 1862, Union General Ambrose Burnside launched a major offensive in eastern North Carolina. After Union forces seized Roanoke Island and captured two thousand prisoners, some Virginia newspapers blamed the 31st North Carolina for breaking ranks and fleeing from the battle. In the battle for New Bern, North Carolina militia ran, further eroding the state’s military reputation. Even worse, when Burnside sent troops to Washington, North Carolina, in late March, the citizens who had not fled to the interior welcomed the Union soldiers. Some of the Confederate planters, before leaving the town, had broken open thousands of barrels of turpentine and dumped them into the Tar River rather than see them captured by Union forces.14

Frederick Douglass, ca. 1874, by George K. Warren, National Archives and Records Administration.

In the aftermath of the raid on Washington, there is another clue. Union prisoners held at Salisbury, North Carolina, were transported to Washington in June 1862, now in the hands of the federals, to be exchanged. Just before arriving, they bathed in the Tar River, but they “stirred up the river bottom so much that the tar smeared their bodies completely, each man coming out of the water with a stick to scour the tar off their bodies and legs.” This story seems just about plausible, but perhaps more interesting is the recurring intersection of tar on the body (including legs and, presumably, heels), this particular region of North Carolina, and loyalty to the Union.15

The earliest usage I have found of North Carolina soldiers being called “Tar Heels” comes from the Seven Days’ Battle in late June 1862 near Manchester, Virginia. A member of Ransom’s Brigade later recalled banter with Virginia soldiers: As we were approaching the Virginians, I noticed a big, burly, dark-visaged Lieutenant step out before his companions, as though he was to be the champion of their side. He was of so dark a complexion as to indicate descent from Pocahontas or of some one else not belonging to the Caucasian race.—The wink was given to our “acknowledged wit” and he moved over to the side next to the Virginians. The dark-visaged Lieutenant noticed the movement and at once accosted “old Stonewall,” the name by which our wag was known.

Lieutenant.

“Halloo, Tar-Heel, did you know that Tar River was burnt up.”

Stonewall.

“No I did’nt, hoss, is it true?”

Lieutenant.

“Oh yes, I was there and saw it burn up.”

Stonewall.

“Well, I am afraid it is too true, for your face looks badly smoked.”

Several elements of this exchange are worth noting. The mention of the Tar River would seem to refer to the attack in March 1862 discussed earlier. By calling “old Stonewall” a “Tar-Heel,” it is possible that the Virginia lieutenant was blending “rosin heel” with “Tar River” to create a new moniker, “Tar Heel.” There is also a strong element of racialization present. If “tar” had a racially black value at this time, then the Virginia lieutenant’s comment is meant to disparage the North Carolinian by impugning his racial identity, suggesting that though white, he is so poor that he might as well be black. “Old Stonewall,” though, turns the tables on the “dark-visaged” Virginian, who “was of so dark a complexion as to indicate descent from Pocahontas or of some one else not belonging to the Caucasian race,” by suggesting he was “smoked.” “Smoked Yankees” was a nickname later applied to black Union soldiers, and “smoke” was a slang term for African Americans. The racial aspect of the encounter is emphasized by the use of italics to remind the reader that the Virginian was “dark-visaged.” It can never be proved precisely, but this exchange (and perhaps others like it around the same time) is probably where the term “Tar Heel” first was applied to North Carolinians.16

Most North Carolina soldiers who were called “Tar Heels” reacted not with the quick wit of “old Stonewall” but with hostility if not outright violence. One undated example comes, again, from an encounter between Virginia soldiers and Pettigrew’s Brigade from North Carolina. One “last straggler had passed, and all the Virginians were about to return to their tents, when a small, bilious-looking, sallow-faced, tar-smoked, North Carolinian” came past.

Virginian.

(Mockingly.) Mister, what ridge-ment do you belong to?

Straggler.

B’long to 52d Kliner, you ugly cuss, (cocking his gun) now say “Tar-heel,” and I’ll put daylight through you! The obnoxious word was not said!

As before, the North Carolinian is described as “smoked,” and this time, “tar” is directly associated with “smoked.” Sometimes the “obnoxious” word was said, with dangerous results. A Virginia soldier in Richmond said to a North Carolinian, “Go to hell, you d—d tar heel,” which set in motion a fight that ended with the North Carolinian badly beaten and two Virginians shot, one fatally.17

Before long, though, North Carolinians began to turn the tables on “Tar Heel,” making light of the nickname and turning it into a way to insult soldiers from other states and then adopting it to describe themselves. By about early 1864, it was widely known and no longer seen as disparaging. One anecdote that was widely repeated originated in March 1863, though its circulation was boosted when it was retold in the New Orleans Picayune in November 1864. The scene as later described in the newspaper went like this:

Going through North Carolina, by rail, in company with some Georgia volunteers, on their way to Virginia, they stopped to “bait,” and during the meal, says the narrator, a robust Georgia trooper hailed one of the many loungers about the station with:

“Say, old tar-heel, got any tar for sale?”

The native so addressed answered rather shortly to his “gallant defender,” “No, sir-ee.”

“W-a-l-l, you’ve got some pitch here, haven’t you?”

“Nary pitch,” answered the sandhiller.

“Well, then, what have you done with ’em, for you know you live on such stuff?”

About this time the long, lean specimen of a tar-maker brightened up and replied, “Well, we sold all we had to Jeff Davis.”

The Georgian, thrown off his guard, could not resist asking, “Why, what did old Davis want with all the tar?”

Quoth the man of pitch: “Why, you Georgians run so, that he had to buy something to make you stick.”

The shouts of laughter that greeted this sally effectually squelched the demonstrative Georgian for the rest of the day, and no more “tar-heel” queries were ventured until the train reached Petersburg.

This kind of banter, with the more sophisticated traveler trying to make fun of the backwards local, only to be made a fool of himself, is a common form in southern folklore, most widely known in the “Arkansas Traveler” skit. However, this story from March 1863 actually comes after at least some North Carolina soldiers had begun using “Tar Heel” to describe themselves. A month earlier at Fredericksburg, a snowball fight between the 1st N.C. and the 3rd N.C. on one side and Louisiana and Virginia troops on the other featured a flag carried by the North Carolinians: “The colors had inscribed on one side, ‘Tar Heel Boys’ and on the other were the Stars and Bars.”18

Tar Heels have always been white and black, and other colors as well.

If we cannot say for sure when the phrase “Tar Heel” was first used or first applied to North Carolina soldiers, we can say fairly precisely when it was given something like an official seal of approval: March 28, 1863. On that day, North Carolina governor Zebulon Vance gave a speech to the 39th North Carolina in their quarters near Orange Court House, Virginia. According to the newspaper account,

The Governor was introduced by Gen. Ramseur. He began his speech by remarking that on Saturday he addressed his hearers as “fellow soldiers,” but on second thought, he recollected that although he was once a soldier, he was not one now—having skulked out of service by being elected to a little office down in North Carolina—and he felt that he had no right to greet them by that term—They were not his “Fellow-citizens,” and he knew of only one other term to use—a term that had been given them by their comrades from other States—“tar-heels”—and he would borrow the term, and address them as “Fellow Tar-Heels.”

After this, the use of the term becomes even more widespread, and by the end of the war, “Tar Heel” seems to have been in general usage to describe not only North Carolina soldiers, but anyone from the Tar, Pitch, and Turpentine State.19

The proud name of “Tar Heel” is thoroughly stuck to questions of race and class, and its history is full of ironies. Earlier, more cursory examinations pinned its origins to white North Carolina soldiers fighting to preserve slavery. That origin suggests, however subtly, that the true Tar Heels were those white soldiers (and their descendants), not so much the descendants of those North Carolinians they fought to keep enslaved. Yet this more complex tale of the origins of “Tar Heel” shows that it is rooted in hard work by poor people, work that dirtied the bodies of both enslaved Africans and poor whites in the Piney Woods. North Carolina in the Civil War was a divided land, and not all North Carolinians, even white ones, supported the Confederacy. It is out of this disloyalty to the Confederacy that North Carolina soldiers came to be given the racially derogatory nickname of “Tar Heels.” “Tar Heel” means “black” at some level, or at least not fully “white,” if whiteness is defined by supporting slavery and the Confederacy; and that is a good thing, because Tar Heels have always been white and black, and other colors as well.

Bruce E. Baker is the author of several books about the South, most recently The Cotton Kings: Capitalism and Corruption in Turn-of-the-Century New York and New Orleans (Oxford University Press, 2015). He earned his PhD in history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He lives in the Scottish Borders and teaches in England.

JP Trostle is an artist and illustrator in Durham, NC, who has worked for Indy Week and other area newspapers. He painted the colors tints above using an old bottle of turpentine he found among his late mother’s art supplies. See more of his work at japenet.net.

This essay was first published in Southern Cultures, Vol. 21, No. 4, Winter 2015.

–southerncultures.org