Helen Gregg was 6 years old when her world blew up.

She remembers vividly the day in 1958 when she was playing in front of her childhood home outside Florence when everything was shook by an explosion — the result of the accidental aerial release of a nuclear bomb. “It was sunny. It was a pretty day,” said Helen Holladay, as she’s known now.

“Then the ground started shaking, things were hitting us in the head … everything that was destroyed up in air was coming back down on us, pieces of timber and everything.” Unlike other kids who grew up during the Cold War, Holladay had never done the “duck and cover” drill in school, “but if we had been trained, we’d have known what we did was right,” she said.

Dropping to the ground just felt like “the safest place to be.”

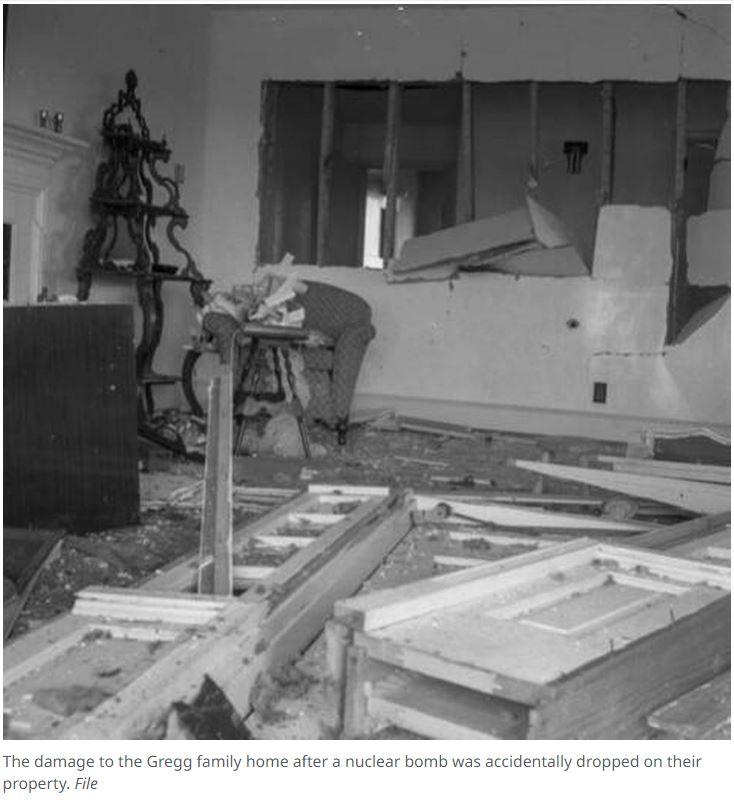

When she looked up, her house was partially collapsed, and her father, Walter Gregg, and brother Walter Jr. were walking out of the garage covered in blood.

They had no idea what had happened. Her father, who worked for the railroad, initially thought a plane had crashed. But what actually happened was one of the rarest events in the history of the atomic age. A passing U.S. Air Force bomber had accidentally released a (fortunately unloaded) nuclear bomb in transit from an air base in Savannah to Europe.

Had the fissile material been loaded into the bomb, the accidental release could have spread radioactive material across the Pee Dee.

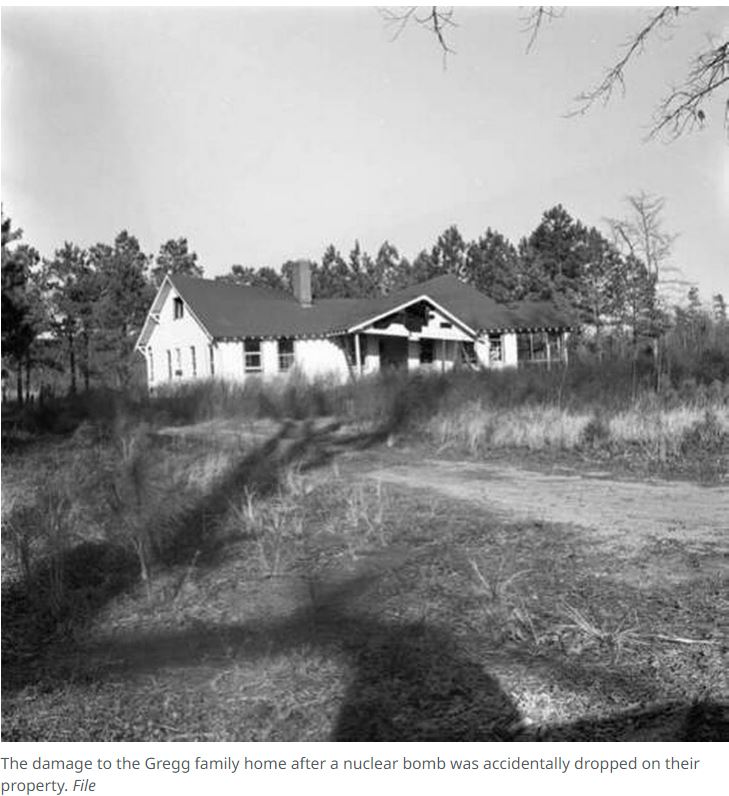

As it was, the bomb’s conventional TNT payload still did significant damage to the nearby Mars Bluff home of the Gregg family when it landed in a wooded area on March 11, 1958, and left the family with superficial but still-frightening injuries. “My mother was injured the worse,” said Holladay, now 72. “The house caved in on top of her, and she had cuts all over. Daddy had cuts over his back, because he was standing over my brother trying to get out of the garage that was falling in.” No one was killed in the blast.

The highly destructive weapon was dropped through sheer human error on the part of the flight crew, said Stephen Motte, curator at the Florence County Museum, which has an exhibit on the Mars Bluff bomb incident. “They were flying at 1,500 feet, approaching Florence, and the pilot had noticed that the indicator light in the cockpit had come on,” Motte recounts. “There was a problem in the bomb bay, so the bombardier went in … the space was not much larger than the bomb is. He stands up to get a better look, and he reaches up and grabs something, and it turns out it was the emergency release cable.”

The bomb was released from its clamps and fell on the bomb bay doors, which held for a “second or two,” before breaking open and dropping a military-grade warhead on the Gregg home just east of Florence. While the plane circled above trying to assess the damage, the Greggs were picked up by a passing car on Highway 301 that had seen the explosion and were taken for treatment.

“Local people responded first, and that’s why the story made it out to the media,” Motte said. “The Air Force did not want to tell this story. It was the Cold War, tensions were high, and people were certainly fearing the worse.”

‘WE WALKED AWAY WITH NOTHING’

The Greggs’ property was eventually surrounded by military personnel who prevented the family from returning to their home, partly to maintain secrecy and partly because of fears of radioactive contamination.

“We couldn’t even wear any of our clothes,” Holladay said. “They had them cleaned from the house, and they itched so bad. They sent them to laboratories to check them out.” It turned out “the impact was so great, it infused the insulation out of the wall into the clothes,” Holladay said. “We walked away with nothing, absolutely nothing.”

Holladay doesn’t believe the Air Force treated the family very well after their ordeal, and they ultimately took the government to court to receive compensation. She also recalls one particular return to the damaged old house, after the family had moved into her aunt and uncle’s nearby dairy farm.

”We had a cat at the time, and they wouldn’t let back on the property,” she said. “So we snuck through the woods and found our kitten behind the refrigerator and took it to my aunt and uncle’s next door.”

But the outpouring of support from the community was overwhelming. The manager of the local store told Walter Gregg to take whatever his family needed and pay for it as they could. Holladay’s aunt took the furniture from a family beach house and used it to furnish a small apartment for the displaced family.

“If not for the good people of Florence, we would have never made it,” she said. “The government did nothing for us, except give us a hard time.” During the family’s suit against the government, the Greggs were told the crew of the bomber was stationed overseas and unavailable to be called to court.

But about seven years after the bombing, Holladay remembers the pilots visiting the family and offering their apologies.

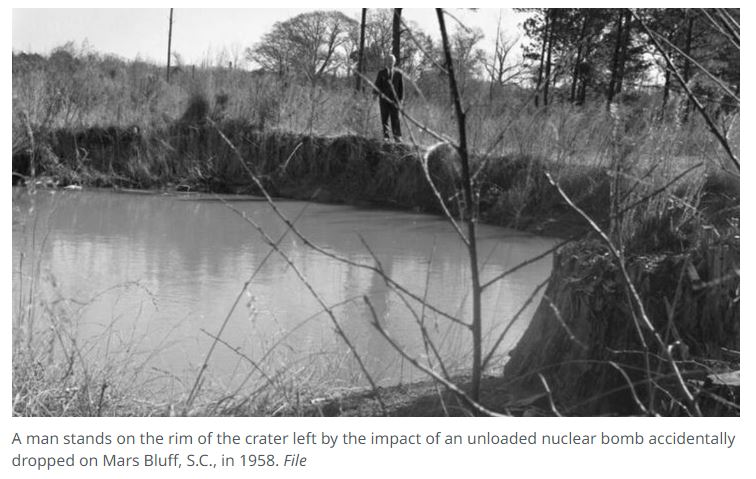

Over the years, the bombing was largely forgotten. The Greggs’ home was pulled down and they moved into Florence. The crater from the blast is still visible, and at one point a private kiosk with information about the bombing was erected next to it, but it otherwise remained in an undeveloped wooded area.

“The crater itself was behind the treeline, so you wouldn’t know it was there unless somebody showed you,” Motte said. “There’s a state historical marker nearby (on U.S. 301, roughly a mile away), but it’s a bit misleading, because it’s not that close to the crater site.”

As the area has slowly developed, the fence of a private home now backs up to the crater, and further growth in the area may swallow it up completely.

While the explosion was a big deal for her generation, Holladay said today “younger people don’t know anything about it.”

Motte says Florence’s growing population means fewer people there have any connection to the event. But he says it still deserves to be remembered for the unique event that it was.

“You wouldn’t be afraid your own government would drop a bomb on you,” he said.

–thestate.com