Surrounded by stacks of yellowed books, resting in a stained yellow chair and imprisoned in a ruined yellow body just two months from collapse, James Dickey’s eyes welled with tears he made no effort to conceal.

It’s been 15 years since his death and 40 years since Deliverance hit movie screens on July 30, 1972, catapulting both him and it to an international fame well beyond his already-staggering poetic accomplishments.

Looking back on that time as his student, though, I find my lingering memory of the man wasn’t hearing tales of his debauchery, enjoying his vicious barbs at the expense of poetic peers or even marveling at the enormity of an intellect that despite his body’s steep decline was in full possession of its power.

No, through the lens of a decade-and-a-half, I simply remember a dying man missing his brother.

As a M.F.A. student in his final two graduate poetry courses at the University of South Carolina, I had been invited to his Lake Katherine home under the auspices of introducing him to Mike Shavo, an attorney and friend of mine who was an avid fan of film in general and the Coen brothers in particular. It was November 1996, and the Coen brothers, coming off the massive critical and box-office success of Fargo, had just agreed to direct the film version of Dickey’s final novel, To the White Sea, about a tail gunner shot down over Japan in the final days of World War II who endeavors to trek across enemy territory from burned-out Tokyo to the northern island of Hokkaido. Brad Pitt already was slated to star.

Day after day in his final classes Dickey would give us updates on the latest gossip regarding the project, which was attracting interest from the biggest names in Hollywood. First Clint Eastwood was determined to direct, then brothers Joel and Ethan Coen, who until that point only had written their own scripts, agreed and the project was moving forward. (In fact, in an Oct. 18, 2007 interview in Time magazine after filming No Country for Old Men, the brothers claimed filming a work of literature was an “itch” they’d been looking to “scratch” since To the White Sea was shelved in 2002 due to lack of adequate funding – an estimated $80 million, according to a 2011 interview in Creative Screenwriting magazine, which named the project one of Hollywood’s “10 Dead Projects We’d Like to See Resurrected” and in which the brothers expressed remorse that it never got made. Ethan said the money just wasn’t there for it “…even with Brad Pitt basically doing it for free.”). In late 1996, however, the project was a ‘go,’ and Dickey, a huge film buff himself, was eager to learn everything he could about the Coen brothers’ work.

To that end Mike brought several of their screenplays for him to read, and aware of the momentous honor we were accorded with such a visit, we also came bearing bottles of Glenlivet Scotch and Maker’s Mark Bourbon. This would prove to be a decision with consequences I only would learn of later. At the time we simply helped ourselves upon arrival, which Dickey warmly encouraged us to do, though he did not partake himself owing to his physical condition.

By then, suffering from the cumulative degenerative effects of a rampaging alcoholic career and its associated ailments, he could not walk 10 feet without having to stop, sit down and gather his breath before moving another 10 feet and repeating the procedure. Just making it to the classroom on campus in the humanities building twice a week that fall was a Herculean ordeal by itself. He continued this until his final class, given just six days before his death on Jan. 19, which was held at the house he was no longer in condition to leave, the house where just a few feet away a few weeks before we had sat one late November afternoon with the setting sun dappling the room, good drinks in our glasses and Dickey – for God’s sake, James Dickey! – making us feel important as we talked about the movies.

Mike smartly praised Dickey for his underrated acting turn as Sheriff Bullard in Deliverance, which somehow or other turned the conversation to his large brass belt buckle, which had “CSA” emblazoned on it for the Confederate States of America. It was a gift from his younger brother, Tom, a former track star at LSU (he was the Southeastern Conference champion in the long jump in 1946; 100-yard dash and 220-yard dash in 1946 and 1947; 440-yard dash in 1947 and 1948; and was the league’s individual high-point scorer at the 1946 and 1947 meets). Dickey, a track standout himself in the high hurdles and, briefly, a halfback at Clemson before World War II called, showed us a picture from Tom’s collegiate track days and spoke at length about the brother he so dearly loved.

The belt buckle was a present Tom had unearthed through his considerable work as a passionate Civil War relic hunter, a field of endeavor in which he had achieved no small measure of fame in his own right, so much, in fact, that according to The Atlanta History Center’s website, he “acquired the largest and most comprehensive collection of Civil War artillery projectiles in the United States.”

It was about this peculiar hobby that while in school at New York University in 1974, Dickey’s son Christopher, now Paris bureau chief and Middle East Regional Editor for Newsweek, made a documentary about his uncle entitled War Under the Pine-Straw. Once on the subject of that film, his enthusiasm about it and for his late brother, who had passed away in 1987, ensured we would be watching it directly. After refilling our drinks, we settled in to do just that.

The film itself was extremely well done, and I still vividly recall its opening. It featured a rather famous Civil War photograph showing stacked rows of bloated, grotesque bodies following a battle that faded gradually into a shot from the present day taken from the same camera angle and location in a neat trick of cinematography. As the still starkness of the black-and-white photo faded into the lushness of greenery, with a gentle breeze blowing and a dog barking in the distance, Tom Dickey emerged from the bushes wearing his World War II-era mine detector and walked through the frame, left to right, over where the bodies once lay across to what is now a nicely manicured set of tennis courts where elderly players were enjoying the afternoon.

It was a scene of suburban leisure so entirely alien to the horrors of the original photograph that the dichotomy between the Old South, with its distended corpses and savage destruction, and the economically revitalized New South, with its country-club culture and affluent diffidence toward the more unpleasant aspects of its past, could hardly have been more powerfully presented.

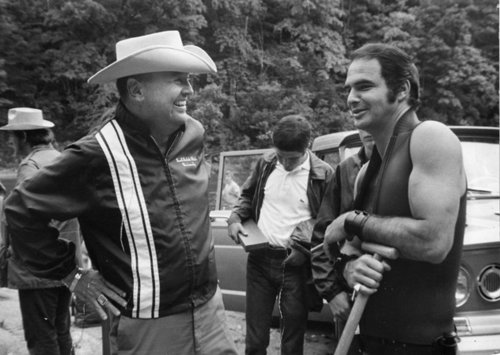

James Dickey and Burt Reynolds on the set of Deliverance. According to a September 2011 issue of Atlanta magazine, Reynolds says, “Dickey and I didn’t see eye to eye, but I did love the book.” Before Dickey was banned from the set owing to his disruptive presence by director John Boorman, he earned the scorn of Reynolds and the other lead actors by calling them by their character’s names and not their real names. Source: breathnaigh.org

The movie proceeded following his brother around as he drove through various neighborhoods in Atlanta and elsewhere trying to trace the routes of those lost armies, knocking on the doors of houses to get permission to explore their backyards and clowning around with the massive collection of unexploded Civil War ordnance in his garage.

Mostly, though, the film was a tribute, an homage, to Tom and his infectious personality and charm, though through it all I found myself watching Tom Dickey less and James Dickey more. I became suddenly aware that he knew he was watching that film for the last time, was seeing his brother for the last time and was enjoying it with such intensity that it struck me emotionally as well, for it was a profoundly personal moment and one I felt distinctly unqualified to witness.

And yet there I was, and there he was, The Great Man, dying in front of everyone but still making time for students, still opening his home and still sharing moments of his life so personal that, like his poetry, one finds oneself elated to be swept along in the immensity of their significance as if such moments, such sublime phrasings, always would exist, always had to exist.

As I stood on the Horseshoe weeks later on another sunny afternoon for the memorial tribute, his spectacular wattage remained clear. Present were luminaries from all corners of the literary universe, scholars and critics, best-selling authors, poets and many current and former students, colleagues and friends who gathered to say goodbye just steps away from his favorite on-campus watering hole, The Faculty House, where a plaque in his honor stands to this day.

I still have the program, and reading through it takes me right back to that moment in time – the Capital City Chorale opened by singing “Sweet Chariot,” “Amazing Grace” and “Shall We Gather by the River,” followed by a welcome from Dr. Donald Greiner, a dear friend of Dickey and former professor of mine who once in class explained Deliverance more clearly than I’ve ever heard done before. The novel is to be understood, he told us, in the context of the Great American Novel as essayed most effectively by James Fenimore Cooper and Mark Twain. Its conventions prescribe a protagonist(s) leaving the comfort of civilization to explore the wilderness of America and the natives who live there.

Along the way, the hero encounters difficulty and challenges including death or the possibility of it, during which male bonding ensues, a la Huck and Jim or Natty Bumpo and Chingachgook, and after which there is a return to civilization with a greater awareness of self and the world. Leave it to Dickey to take the theme of male bonding to the level he did and in a manner so shockingly effective that it is firmly embedded in the world’s consciousness, forever and always just a few plucks from “Dueling Banjos” away.

To this day, it still irks Southerners to no end to have been portrayed in such an unflattering manner – or, to have been portrayed accurately, Dickey argued, because though he was the son of a wealthy Atlanta lawyer and educated at Vanderbilt, he told us more than once in class that the closets of all families, Southern or otherwise, are well-stocked with examples of mental illness and homosexuality. In every family, he said, one doesn’t have to look far to find the relative no one talks about, and pointing that out so gratuitously, so uncomfortably and on such a monumental stage provided his provocative sensibilities with ceaseless delight.

In many ways provocation became his avocation, and his lies, as instruments of it, were enormous and prolific. The title of Henry Hart’s 2000 biography of the poet: James Dickey: The World as a Lie, is clear on this point – Dickey himself is said to have suggested the title. Thirty years before his death, in January, 1967, he told an audience at the Carnegie Lecture Hall in Pittsburgh that, “I’d rather listen to a spectacular liar than the truth. Truth is absolutely a relative matter … poetry isn’t trying to tell the truth, it’s trying to make it.”

Dickey made lying for effect, whether to expose a lazy interviewer (of which there seemed to be an inexhaustible supply), demonstrate contempt for a particular audience or challenge a student intellectually, into an art form as few others ever had the will or ability to do both in literature and in life. He would lie to your face, knowing you knew it, and dare you to correct him. Most didn’t. Because of this character trait – I won’t call it a defect, because he was so conscious about it and wielded it with such skill that it deserves, if anything, praise – he was lambasted, belittled and demeaned by a notoriously snobbish establishment to which this loud-talking, foul-mouthed, fist-fighting, oversexed Southerner was not a welcome or pleasant addition. Wherever he went Dickey often made as many enemies as friends, and to the consternation of those who loved and supported him, seemed to relish doing so.

“Pity the Dickey biographer” was an oft-repeated phrase during Dickey’s life, and how just the sentiment then and now. How to reconcile, after all, that one of the greatest literary minds of the century – besides the poetry and fiction, his criticism is as penetrating as anyone’s – came housed in a body used mostly for hard drinking and sex to excesses few in their right mind would condone. He was both the drunken philanderer and the staggeringly gifted poet, musician and teacher. He was an insensitive asshole and tender friend. His mind was as adept with the loftiest thoughts of man as with its lowest, and he reveled in both pursuits. To love Dickey the human being was to accept Dickey the human hurricane, to willingly walk into its path with open arms just to experience that fleeting peek at such power and majesty when glimpsed from the spinning calm at its eye.

His career spanned the skies of World War II to university classrooms to cosmopolitan literary salons. He won the National Book Award for poetry in 1966 with Buckdancer’s Choice, was the nation’s poet laureate from 1966-68, wrote Jimmy Carter’s inaugural poem (“The Strength of Fields”) at the president’s request – both were native Georgians – and earned the kind of international fame most poets only dream of and, subsequently, resent deeply those who achieve it. And many resented Dickey deeply, for such were the legends surrounding Dickey’s drink and carousing career, both accurate and apocryphal, that for decades while alive and in the passing years since his death, too often they were the story of Dickey rather than his work.

Excepting alcohol, he was unstoppable, a force of nature one simply could not ignore whose poetry and fiction rank with the best this country has produced. With alcohol, he became all that lowered to a mean and roused to a cruel energy with consequences painfully endured by those who knew and loved him best, a storm to be ridden out until spent. And spent, finally, his body was.

Which brings me to those two bottles of liquor. Believing ourselves generous, we left them there not for him but for his helpers, for any of the several men and women who kept house, organized his schedule, washed his clothes, prepared his food and generally helped such a man as he did all the things such a man was called upon to do – answer correspondence, decline invitations, compose dust jacket blurbs, return phone calls. Some years later I ran into one of these people, a man who also had been in Dickey’s final two classes with me. He related the following story to me.

He said Dickey’s wife – his second wife, Deborah, a former student he married just two months after the death of his first wife, Maxine, and no stranger to the pain of addiction herself – came to the house not very long after we had visited and found the bottles. Unwilling to believe, after years of grim experience, that he hadn’t consumed any himself, this led to an explosive fight. Furious at him for possibly further jeopardizing his health in such a way, she stormed out, according to the correspondent, leaving him, once more, disbelieved, harshly judged and alone. In his final days, both the reputation and the man suffered such condemnations, and they were not all unwarranted or without merit.

In the memorial program appears my favorite Dickey poem, “For the Last Wolverine.” Written in honor of the fierce primeval creature he so admired and yet was racing toward extinction, the poem and its final lines are as fitting a metaphor for Dickey now as was when they first appeared in his 1967 collection, Falling.

But small, filthy, unwinged,

You will soon be crouching

Alone, with maybe some dim racial notion

Of being the last, but none of how much

Your unnoticed going will mean:

How much the timid poem needs

The mindless explosion of your rage,

The glutton’s internal fire the elk’s

Heart in the belly, sprouting wings,

The pact of the “blind swallowing

Thing,” with himself, to eat

The world, and not to be driven off it

Until it is gone, even if it takes

Forever. I take you as you are

And make of you what I will,

Skunk-bear, carajou, bloodthirsty

Non-survivor.

Lord, let me die but not die

Out.

—

Fifteen years later he hasn’t, he won’t, and thank God for that.

Ron Aiken is a freelance writer in Columbia, S.C.